How Intrepid Lab Sleuths Ramped Up Tests As Coronavirus Closed In

By JoNel Aleccia, Kaiser Health News

While officials in Washington, D.C., grappled with delays and red tape, two professional virus hunters raced to make thousands of tests available to detect the deadly new coronavirus sweeping the globe, hoping to stem its spread in the U.S.

Dr. Keith Jerome, 56, and Dr. Alex Greninger, 38, of the esteemed University of Washington School of Medicine, have overseen the rollout of more than 4,000 tests, painstaking work that has confirmed the infection in hundreds of patients across the nation.

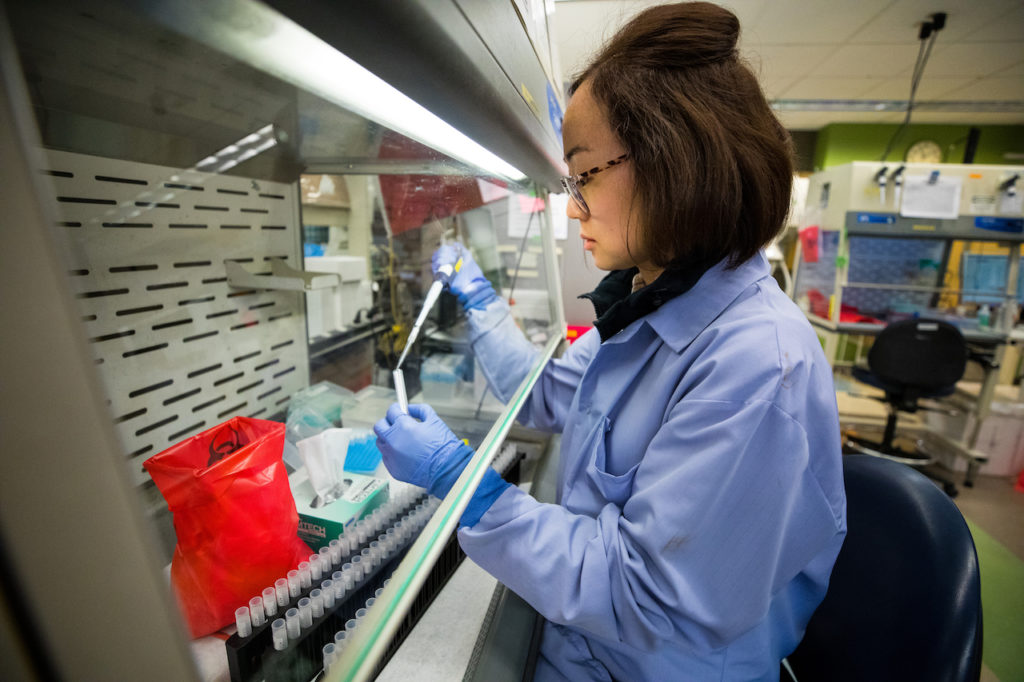

Their 10,000-square-foot virology lab in Seattle’s picturesque South Lake Union neighborhood was whirring with activity on a recent weekday as medical scientists and clinical lab technicians processed samples from patients in the Northwest and beyond. But the virus also has hit close to home.

On the same day the team churned out more than 1,300 tests for suspected patients, Greninger’s 76-year-old mother was waiting for results from her own coronavirus test. She had been living at Ida Culver House Ravenna, a Seattle-area retirement home where a man in his 80s had died two days earlier.

“She’s been on my couch for the past 10 days,” Greninger said. “She got swabbed this morning.”

Meanwhile, even before area schools shut down, Jerome said his teenage daughter decided to study at home for the time being, rather than attend class at her high school, because of the coronavirus risk.

“We had a talk last night and mutually decided that she’s not going to school anymore — for now,” he said.

Jerome, Greninger and their UW Medicine laboratory colleagues were ahead of much of the nation in developing an accurate test for the new coronavirus, and it may be due to that foresight that Washington state has been out front in detecting its spread. The state announced the first confirmed U.S. case of the virus in January, and since has identified more than 640 infected patients, the most in the country. The state also has seen the most deaths attributed to the virus: at least 40 as of Sunday.

On Thursday, Vice President Mike Pence acknowledged that effort, telling the Today show’s Savannah Guthrie, “The University of Washington is doing extraordinary work” regarding testing.

Across the nation, the virus has sickened more than 3,200 people and killed more than 60.

Jerome and Greninger began developing a test for the never-before-seen virus after keying into early reports in December that a mysterious type of pneumonia had emerged in China. Within days, it became clear that more people were getting sick.

“That’s when we talked about it. We very easily came to a consensus that we should get going,” recalled Jerome, a renowned virologist. “I told Alex, ‘We’re probably going to be wasting some money on this. It’s probably not going to come over here. But you’ve got to be ready.’”

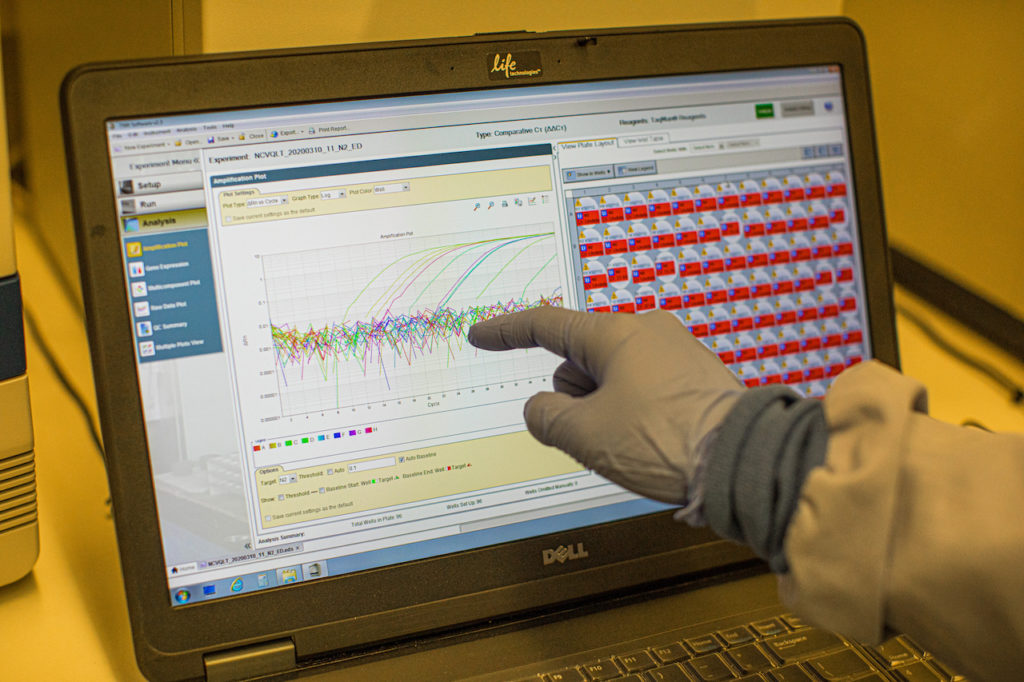

That meant ramping up a test using what’s known as PCR — polymerase chain reaction. It’s a process that searches for tiny bits of the genetic code of the virus in samples taken from the nose and throat. Seattle laboratory scientists have used the technique for years, doing groundbreaking work on HIV, herpes simplex and other viruses.

“This is part of our DNA here. It’s part of our identity,” said Greninger, dressed in a blue hoodie and orange-and-purple running shoes. “For people dedicated to virology, when a new virus comes out, this is what we do.”

After Chinese scientists published the genetic sequence of the virus later in January, Jerome and Greninger went to work. As coronavirus continued spreading in China and beyond, with devastating impact, their sense of urgency grew.

“We knew from China, we knew from South Korea, that when this virus comes into your community, you could be running hundreds of tests a day,” Jerome said. “No one lab has the capacity to do what was needed in Wuhan.”

At first, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta was the only facility in the U.S. authorized to conduct tests for the virus. As demand surged, this vital pipeline for detection and intervention became backlogged and bottlenecked. The issue was complicated by flaws with test kits the CDC distributed to state and local public health labs, rendering them largely unusable.

Greninger pressed hard for the federal Food and Drug Administration to relax a requirement that prevented the lab from testing sick patients. As the public health emergency mushroomed, he and Jerome took advantage of a regulatory loophole that allowed them to test samples obtained for research purposes from UW’s hospitals.

On Feb. 28, a test came back positive. The scientists sent their findings to state officials, and that evening, in a rare after-hours news conference, local health officials confirmed that COVID-19 was spreading in the wider community.

On Feb. 29, a Saturday, the FDA granted a waiver to allow private and academic labs to start testing for the novel coronavirus. Within two days, the UW virology lab was in full swing, churning out test results round-the-clock.

“I slept three or four hours those first nights,” Jerome said.

New equipment is arriving at the lab daily and staff members are deployed in three shifts to handle the load. Jerome anticipates the lab soon will be able to perform between 2,000 and 2,500 tests a day, building to as many as 5,000. They’re working with area officials to boost efforts such as drive-through testing sites.

A portion of tests being processed now come from outside Washington state, said Jerome, who has made tests available to medical practitioners anywhere in the country.

“I wish that more people were getting testing. We need to understand who’s infected, get them the medical care that they might need and also get them away from other people who haven’t been infected,” he said.

On a recent day, about 9% of tests were coming back positive.

“It’s not good,” Greninger said.

“It shows the virus is out there,” Jerome added. “And there’s more than most people realize.”

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Photos by Dan DeLong for Kaiser Health News