A Facebook page I follow recently asked those living with invisible disability:

“What’s the one thing you wish people would say to you?”

It took me a long time to think of an answer. Admittedly, I have tipped over to the visible disability camp the last few years, but I still get the “but you don’t look sick/disabled” comments with such frequency, it would seem I still fall into the not looking sick/disabled-enough camp. Go society and its continued desire to hold on tightly to the myths and stereotypes around disability. But because I have spent enough years in the invisible camp, its legacy is still keenly felt.

A version of “I believe you” was sought by many who answered the question. As was “What can I do to help?” I understand both of these. Belief was definitely lacking at the start, be it from strangers, friends, family or medical practitioners. It was frustrating and disheartening and left me feeling alone. It also took a huge toll on my self-confidence as I internalized the lack of belief and started to doubt myself. Am I really sick? and Should I really just suck it up? were on repeat in my mind. And they were destructive. The current state of my body makes a mockery of those questions. Even at the start, passing out and a heart rate that wanted to go from bradycardia to tachycardia on a never ending loop wasn’t exactly normal. Belief became my holy grail. It continues to be the holy grail for many. Sadly, even with a concrete diagnosis, belief can still be a missing factor. As such, an expression of belief is understandably high on the list of many.

A lack of help is another I understand only too well. As I wrote in “No Casseroles for You,” help is not often forthcoming for those with chronic illness, many of which are invisible. Often just like you can’t see a chronic illness or disability, you cannot see its consequences. Alternately, its chronic nature leads to care fatigue for those around us. When a disorder is measured in years or a lifetime, it is hard for many to maintain caring for that length of time. There are certain illnesses that are known as casserole illnesses. Those whose name inspire instant understanding of need and seriousness. That activate whole communities to action. And then there are those like dysautonomia that are never, or rarely, invited to the party.

Having said that, I know from friends who live with the well-known casserole illnesses and, if they continue on over time, even they experience the affects of care fatigue. The inundation of initial help has an unmentioned but clearly defined shelf life, after which it dwindles away. If this happens for the well-known disorders, what does that mean for those of us who aren’t even in the running? How I longed for someone to bring over a meal or offer to vacuum — especially in the early days where I left work and was struggling to find medications that took the edge of my symptoms. But apart from two people, who have very generous hearts, it never happened. Outside of a couple of specific disorders, there were simply no services for seriously ill moms in their 30s in my region. And living in an area with sparse general services, if family and friends didn’t step up, you were left to fend for yourself.

I know all of this, but still I struggled with a response to the question.

When I sat and thought about my experiences, I realized that I don’t want the people around me to say anything.

I want them to be silent.

Instead, I want them to hear me — really hear me.

In essence, both of the responses regarding belief and help are also about hearing. Hearing exactly what is going on. Hearing what my doctors have said. Hearing the expert knowledge I have about my life and disorder. Hearing about my needs. Not the needs you think I have.

Hearing would alleviate so many problems. And part of truly hearing is active listening.

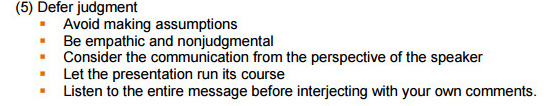

Active listening has a number of parts, but this is the one I really wish others would employ:

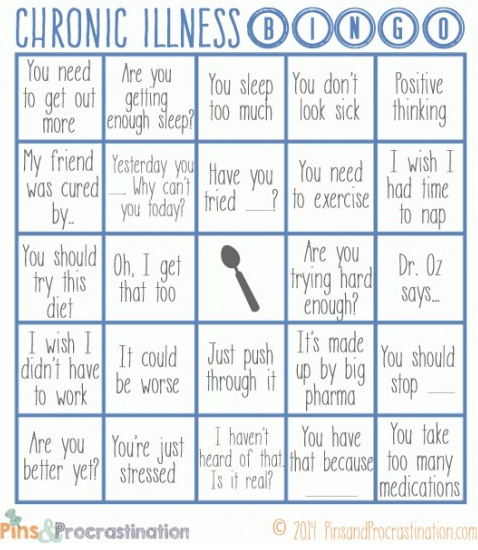

Screenshot source: University of Adelaide: Active Listening

Illness comes with a whole host of judgments and assumptions. I should be better by now, I don’t look sick or disabled enough, I just need to exercise, be more positive, I don’t complain so I must be coping, I don’t need help, it’s not that serious, it’s not like I have [insert illness of choice], if So-And-So can do it, so can you… The judgments are automatic and fired off with relentless regularity. So much so they are parodied on many patient support sites.

Photo source: Pins & Procrastination

They are so ingrained that many do not even realize they are seeing you through that lens, or that their responses are influenced by those negative beliefs.

I don’t want people to say anything in particular to me. I just want them to hear me. To actively listen when I speak. To understand that I am the expert in me and my needs. Being chronically ill is difficult, but so often it is not the illness or symptoms that end up being the hardest part to deal with. Instead it is often the reactions of others to our being ill.

I would add that we are not a homogeneous group. We do not all have the same experiences or needs. And our needs may be different from what you would want in the same circumstances. When I hear fellow patients being told they are ungrateful for simply saying that they didn’t need a particular form of help, or suggesting another way to help only to have it dismissed, it is clear that active listening has not taken place. That they have not been heard.

I know people mean well. I know they don’t intend to make life harder for people who have invisible illnesses or disabilities. But as the old saying goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Stop. Take a step back. Check your assumptions at the door. And listen.

Active listening is a skill. It is not instinctual for many, but it can be learned. And that is a kindness to all.

Hear me.

That is the one thing I want from others.

Follow this journey on Living With Bob (Dysautonomia)

Lead photo source: Thinkstock Images