I’m not dying. I’m not starving. I live in a nice house in a nice neighborhood, surrounded by my friends. I’m employed. I have health insurance. I’m not unintelligent. Things are pretty OK and I plug along every day like everyone else.

What I am is epileptic, with one kidney, depression that would be pretty run-of-the-mill were I able to find an antidepressant that didn’t cause me to have seizures, and a pesky case of stage 4 endometriosis that won’t stay away no matter how many times I hit it with lasers or douse it in progesterone.

Other relevant stories:

• What to Do When Someone Has a Seizure

• Can a Woman with Epilepsy Have a Baby

• Medications for Epilepsy

I won’t spend time here whining about any of the above, because I’m pretty well done with that at this stage in the game. All of these things are genetic. They’re all incurable. Gotta keep going.

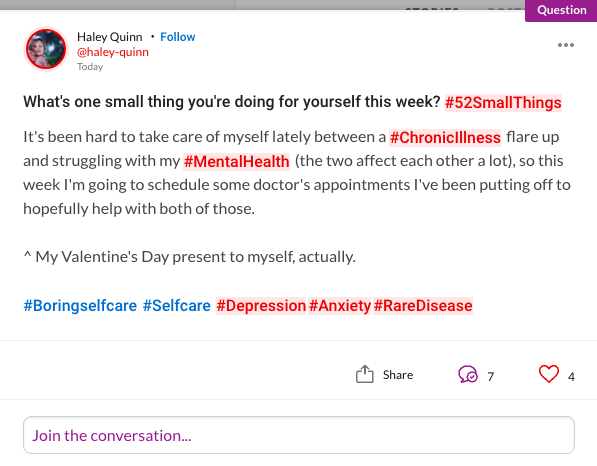

Share some love. Answer the question below.

In some small way, the fact that all of my disorders are incurable is a boon to me. Unlike a lot of other sick folks, my mind and time aren’t constantly anxious and occupied with fighting for some huge end game. My end game is relatively small; to maximize comfort and minimize lifestyle choices that aggravate my situation. My end game is keeping myself together by not getting drunk or doing drugs, not eating junk and getting my eight hours and exercise in. I take my anticonvulsants, my hormones and my pain killers. That’s pretty much it. Sometimes I feel sorry for myself and then I eat some chocolate and spoon my dog.

Here’s the thing — and it’s a very huge thing. These differences that make up a large part of who I am, I’ve recently decided to stop talking about them. I won’t even casually mention them in passing anymore. Why? Not because I’m ashamed. It is because of a single response I get far more often than you’d think. I don’t think I can listen to one more person say some iteration of the phrase: “Just remember you are not your disease/illness/disorder.”

Asking questions is cool and to be expected. That is OK. Compassion and empathy drive these efforts to make a connection and understand. I’m all about connecting. I don’t even really mind if someone tells me their friend tried this or that and it worked for them or, “You’d be surprised how much being positive, or reading ‘The Secret,’ or eating Keto, or Whatever can heal you.” Even if I have to receive that familiar awkward, overly-deep eye contact with a large side of pity whilst being talked at about things I’ve come to terms with and, after all these years, are really no longer a big deal to me, I can kinda hang.

What I can’t do is hear that I am not my illness, that I am not me. I can’t stand to hear another clear, though likely subconscious, implication that these things are too ugly to actually be a part of who I am. In reality, their absence would create enormous holes in my character and the way I see and know the world around me.

The greatest gift I’ve given myself is the acceptance that this is who I am. From birth, I am my epilepsy. From birth, I am my one kidney. Epilepsy is pretty often co-morbid with depression, so I feel comfortable saying I am my depression. Half of the women on my mom’s side of the family have lived with endometriosis. The women in my family have hysterectomies like they’re going out of style. I’m like, hysterectomy royalty. And just as that blue blood pulses through William and Harry, so too am I one with my own family’s painful legacy. I am all these things because who else are we if not the sum of all our parts?

I’m willing to accept that de-personalization from both curable and terminal illness is very often a helpful coping mechanism. The thing that prompted me to write this in the first place was an icky article I stumbled upon by a woman who went on and on along the lines of feeling bad for people who take ownership of their illnesses because they’re only making themselves sicker. This is a huge gut punch to people who can’t be cured. She went so far as to say she cringed recently upon hearing a woman call her Parkinson‘s “my Parkinson’s.” It was almost too offensive to be real and I won’t link it here because I don’t want her site getting hits.

As far as I’m concerned, body positivity messages like the idea that women should love their cellulite and men should be relaxed about hair loss sets a great blueprint for how we should treat self-acceptance of chronic or incurable, non-terminal ailments. If the aforementioned writer was running things, accepting your cellulite would spread it all over your body. If you are one with your receding hairline, you might as well just get it over with and rip it all out, because it’s all coming out very soon. In my mind, the healthy way to live is to work toward the best outcome possible in acceptance of whatever reality looks like for each of us. If you have a lifelong, chronic illness, that is not imminently terminal and you exclude or reject that part or, in my case, those parts, of who you are, it is my opinion — this is very much an opinion piece — you’re not loving your whole self. Unless we’re talking Bezos money and you’re into that sort of thing, I don’t think any of us would volunteer to attach ourselves to a life partner we didn’t love wholly. So, why would you set yourself up for that ill-fate with your numero uno life partner… you?

So much of the advice we all give to others we suspect are in pain is unsolicited. I do it, you do it, we all do it. We are trying to help. I draw the line at the practice of telling someone with a lifelong incurable disorder that they are not their condition. The first time someone said that to me (it was my aunt in reference to my epilepsy), I remember feeling really upset and indignant. I remember not understanding why I felt so angry. Now I know it’s because it was the first time it had ever occurred to me that my epilepsy might be something to feel ashamed of. The message was, “You are beautiful. Your disorder is ugly. Stick to being beautiful.” I also find it offensive when I catch heat for calling myself Epileptic, rather than a “person with epilepsy.” It’s telling me how to be sick and I’ve earned the right to call myself whatever I want to after 32 years of this.

We’re not always going to get it right. I’d wager that 99 percent of people who say things like this are trying to be kind and connect. My ask here is small and specific. Please assume that even if an incurably ill person explicitly proclaims self-hatred related to their illness, they don’t want to be told to pretend the part of themselves they’re desperately trying and need to love isn’t there. They also don’t want to be told how to refer to their disorder or illness. The same is surely true for a self-loving flawed human like me.

Getty image via Anna Ismagilova