What does having fibromyalgia feel like? I’ve read numerous descriptions and, although there are definite themes shared among us, every person’s experience is unique. I tried to find a blog post that captured all of my particular symptoms with perfect eloquence. I couldn’t. What I found is that, even though I think I’m struggling like a Christian martyr trudging up a slope strewn with shards of ice, rusty screw guns, and carnivorous sticky buns, there is always someone whose pain is worse. Sometimes much worse. That doesn’t offer me much solace. It just makes me sad.

- What is Fibromyalgia?

- What Are Common Fibromyalgia Symptoms?

But I do want to explain how fibromyalgia makes me feel. It might help when a friend or loved one doesn’t understand why I keep grimacing during, say, a board game. Maybe after reading this post they will say: “Ah! You feel as if someone has turned your sinews and muscles into sharp metal strands, and is now braiding them quite viciously,” or “Well, no one cares for nails made of hot gravel being pounded into their joints! I’d grimace, too. Carry on, it’s your turn.” Or even “Malevolent sticky bun latched on to your brainstem again, what? No wonder you’re so sluggish and foggy-headed!”

Here’s a simple experiment. It may seem unseemly and unpleasant. First clench one hand tight into a fist. Now choose a part of that fist and bite it, for as long as you can tolerate. Your curled fingers will do. Give it a fair amount of pressure. Give it five minutes, if you possibly can. Notice what happens.

The immediate “victim” of the bite, your clenched fist, will begin to protest. It’s already remorselessly tight, and now something is biting it? Seriously?! Not good. But, there’s more! Soon, your jaw may become tense and tight, even sore. The exertion of holding the fist, along with the bite, will begin to seem intolerable. All you have to do to release the pain is to open your mouth, open your hand. Why are you doing something so ridiculous as biting your fist, just because I suggested it? Please do not do this in public.

If you have fibromyalgia, you probably know where I’m going with this analogy. If you know a loved one who has fibromyalgia, you might have your whole fist stuffed in your cakehole at the moment, and are feeling surly, and I appreciate that.

Fibromyalgia feels as if your body is gnawing on itself, every minute of every day. (Even on the “good days,” when it’s just gnawing with less fervor. On the best days, it still nibbles, like an itch that can never be scratched or eliminated.) As I’ve suggested, your body itself is already intolerably “tight.” It has become a fist that never opens. Then, you visit it with numerous indignities, and they are certainly not confined to the hand — you sink pain into the neck, into the knees, into the edge of the jaw itself. Note that I do not use the passive voice in the sentence above, because you sense that your own body is conducting this cruelty.

You become intolerably aware of the pain. You are the jaws of the predator, and there is no pleasure in being the predator. You will never kill your victim. You are a fox worrying the rabbit to death, over and over and over. Unlike an actual fox, you feel the rabbit’s pain. You aren’t even hungry. You feel remorse for the rabbit. The rabbit and the fox, the jaws and the flesh and the pain and the grief, are bound together forever in a singular dance.

If you are still biting your fist, stop, you fool. You probably look ridiculous, with tears springing to your eyes on the Metro North. You probably look like a woman who wants to scream because she is so heartbreakingly frustrated and is biting her fist to prevent herself from doing so.

Thank you for trying, if you did, but no one should suffer for very long. Where does that leave me? Some mornings, when I wake up to another day of stiffness and aching and mind-numbing pain, the phrase, “What did I do to deserve this?” sometimes springs into my head. I really thought today might be different. I limp my way down the stairs, leaning heavily on the banister. My entire frame feels off-balance and wobbly. Trembling hot shards of pain fire through my shoulders, knees, elbows. My upper back and neck burn as if I’ve been beaten heavily with a cudgel, scalded, racked, and seized. I think that maybe the nasty local gang, the “Sharpened Hot Sporks Laced-With-Acid Boys,” took me down last night, unawares.

Then there is the horrible malaise and fatigue. Making even the simplest breakfast for my sons feels exhausting. Bending down to pick up a bowl from the cupboard, walking it to the breakfast table, removing a carton of milk from the fridge, returning to retrieve a spoon from the cutlery drawer, extracting a box of cereal from the cupboard, setting it on the table — a series of small steps that is, somehow, torture. Every move hurts, in varying degrees, and depending on the day.

My sons are perfectly capable of all these tasks, of course. But if I were to languidly dictate orders from my fainting chair, I fear I would become the cover girl for “Bad Parenting” magazine. As I write this, I realize that delegating every single task in the house would be the best thing for my sons. It wouldn’t hurt them one single tiny bit, and they have energy to spare. It’s just my guilt that keeps me on my feet, thinking, “I should be a better parent. I should have more energy. I shouldn’t hurt.”

I have never been a person to collapse on the couch, except when I’ve come to the very end of my rope. I have to keep going all the time. I can’t sit still. My mother, in her late 80s, is the very same way. She will insist on painfully ascending the stairs to the second floor just to ensure the pillows on the guest bed are fluffed, no matter how many protestations we utter. She will wander around endlessly, buffing the counters, long after she should be in bed. I’ve despaired of her perseverance, yet I am proud of it in a way I can’t explain. Well, yes, I can. I explain it this way: We are not lazy people.

So I don’t stop, ever. A day without exercise is wrong. My overactive mind will punish me for it. My body will feel restless and unfulfilled if I didn’t swim or bike or walk or run, even if it is simultaneously crying out in agony. I can be utterly exhausted, defeated, and in agonizing pain — in a place where I have no business anywhere but in bed or on the couch — and I still insist on exercising, hauling firewood, dragging around set pieces for the middle-school musical, playing piano, toting groceries.

Being Strong and Tireless is part of who I am. A me that isn’t “strong and tireless” isn’t someone whom I would recognize or even care to know. I’m the person who can pick up the 80-pound canoe solo, if asked. I’m the mom who can swim a mile and then spend another hour playing “pull-up” with the kids (a vicious form of Sharks and Minnows in which you literally have to dive down deep to capture your minnow and drag him/her to the surface). Why, just two days ago I was hauling a huge and recalcitrant fake Christmas tree, part of the decor for the middle-school musical, out of the school foyer. The damned tree was collapsing on my head, barfing out ornaments and tinsel. I was sweating and grunting. A man paused and asked if I needed help. “Oh, no thank you, I got it,” was all I said. Then I went and got another tree, and dragged that one out, too.

I felt good dragging those trees. I felt like the warrior I know myself to be. I didn’t hurt a bit while I was dragging those trees. I would have dragged a thousand trees. I don’t know if this is true of anyone else with fibromyalgia, but sometimes the harder things are the easier things. They make you completely forget that you are all torn up inside, because, after all, every day and every moment you are all torn up inside. Lifting rocks and bricks and boards makes the “torn up inside” feeling make sense. Of course it should hurt to drag that heavy load. It would make any healthy person hurt. Therefore, I am healthy. Or just very stupid, because I probably pay for my exertions later. Plus, I won’t take a moment to rest.

It’s the little things that hurt, the small and ordinary offices of life. Putting away laundry is just dreadful, and that’s probably true for people who don’t have fibromyalgia, too. When I hear, “I need help turning on the water for my tub!” from up the stairs, my mind bends and wavers. It’s a weary climb up one short flight, a cranking of handles. Why does something this small have to be so painful? When I pass the pile of papers and school photos that should be trimmed and filed and put away, I always think: “I’ll do that tomorrow. I’m far too tired today.”

It all feels rather hopeless, sometimes, because even watching television is painful. How could watching a television be painful? As I sit there, trying to focus on the plot and to lose myself in the story, I am bitterly aware of my muscles spasming, of my utter failure to relax, of the tight hold the invisible, gnawing thing has on my neck and shoulders. Sometimes I stretch, and my tight joints protest. At other times I try a little self-Reiki, palms to jean-clad thighs, and I wish the pain away.

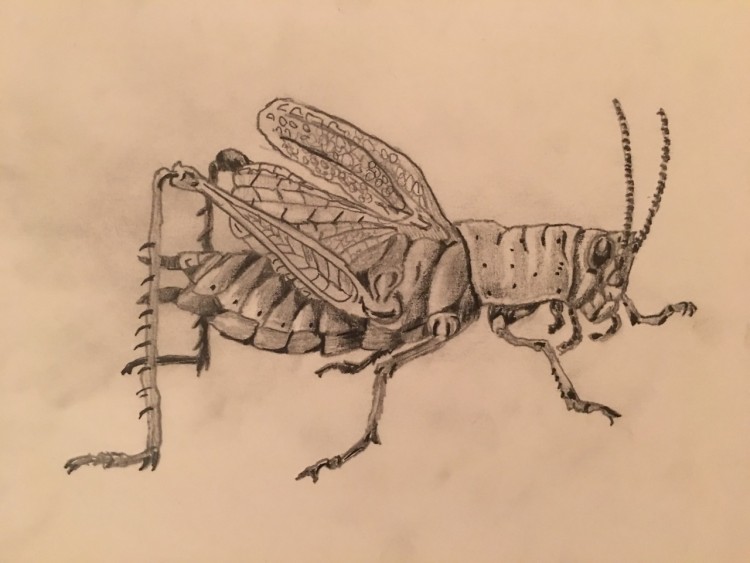

I have been successful on a few occasions. Sometimes it recedes, and I am able to forget (for one minute, two minutes, three minutes?) who I am. This happened two days ago while I was drawing this grasshopper. I used the book “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” and I drew a grasshopper upside down, in an attempt to shut down my anxious time-clock left brain and activate my right brain.

Guess what, little grasshopper? My pain went away, while I was drawing you. Now that I’m writing this, it’s back in full force. It eats away at the base of my skull, and at my shoulder blades, and inside the architecture of my knees, and it burns along my back, and here I am staring at this grasshopper and I know that while I drew it the pain was still there, somewhere waiting on the sidelines. But it didn’t matter. Because I wasn’t trapped in my body. I was calculating the precise distance between wing and leg, and dreaming of hauling big loads.

I don’t have any real wisdom to give. The only things I have ever figured out are to stay busy, to not be lazy, and to keep on, and on. Never give up. Keep doing. I’m still in pain. Sometimes it’s bad. Some days, really bad.

The fox is still dancing with the rabbit. The rabbit gives itself wholly, unwillingly — taut as a wire. The fox digs in with claws and teeth, but it has no love of the conquest. I watch their exertions with my clenched fist held between my teeth, praying for absolution. Praying that I can hold on long enough to be a proper poet for the fox, the rabbit, and the breaking day. Give me enough time.

We want to hear your story. Become a Mighty contributor here.

Lead photo by Thinkstock Images