“Oh my goodness, I’m so sorry, I hadn’t seen you there,” said the store clerk in line in front of me at the coffee store. I had my cane with me, and she had backed up into me and almost run me over. She was quickly apologizing, clearly very sorry.

“I used to have a cane,” she said. “Don’t ever stop fighting. Don’t give up hope. You know I went through treatment, every day. They told me I’d never wear high heels again! I started back with wedges. But look at me now.” She smiled at me, standing proudly without a cane. I listened as she went on, and the coffee shop went quiet. The barista watched her and everyone went into a sort of awkward silence, listening to her as she talked at me with my cane, with me silently standing there, just trying to get my drink.

It was sweet of her. I was touched. I realized she was trying to be nice. People do sometimes talk to you when you have a cane. In my experience, they mean well. They like to ask about the cane, ask how you got the cane, what happened to you, etc. A cane can be something “unusual,” something to comment on. And I am not offended by what she said, though I didn’t like being picked out of a crowd like that just because I had one. Her message was nice enough: not to give up. She must have thought I was injured.

But there is no cure for what I have. I will probably have a cane, on and off, for the rest of my life. Because I have a disability.

I was diagnosed with lupus and fibromyalgia when I was 22 years old. It was a life-changing diagnosis for me and I vividly remember being told how much it would impact my life. I certainly did not believe it would at the time, being in University, a thriving, invincible, young, 20-something girl. How could I lose my ability to function like this on a daily basis? I’m just sick for a little while, surely. This will all go away, we all thought. I went to six different doctors.

Early on, I got walkers, more canes, wheelchairs. Flares came, flares went. Many years went by, and flares came and went. But they never went and never came back. They never went for good.

With each flare came the hope that maybe it would be the last one. Maybe this time, I’ll be better forever. But they would always come back. They would come back and the hope that had returned when the flare had disappeared, disappeared with it, and yet again, I would have to accept my illness and lack of functioning as a part of my life. The loss that it brings with it. With each flare, I would feel, as if all over again, the grief of when I was first diagnosed, and the anger that I have to go through this. Why should I? Why can’t I just have it happen once? Why does it happen out of nowhere? Why does it happen and then go away and come back? Why does my life return and I gain so much back, maybe even some work, school, or sense of balance, and then have it taken away because the illness returns? It feels like two steps forward, two steps back, a dance that never goes anywhere.

Because of this cycle of flares coming and going, my level of functioning certainly has changed. Illness changed my ability to rely on myself because I didn’t know when a flare would come next. I couldn’t be as reliable to friends, school, work, or many other things I used to find so important, because I couldn’t rely on my health to show up as it changed so rapidly. I never knew when a flare would show up or when I would have a good day or a bad day.

Over time, my house began to fill with markers of disability. Aside from the assistive walking devices, I decided one day to get a disability parking permit. Like many people with chronic illness, I was a full-time patient, speaking to doctors, going to appointments, etc. I spent a lot of time on the phone with the pharmacy, that was the worst one, and I spent a lot of time feeling sick.

Since being diagnosed, I have not been able to return to work or anything similar. I had to find an alternate career, and though it turned out for the best, I still have the goal that one day my health will be good enough to return to the level of work I had prior to my diagnosis.

But what do all these markers of illness mean for me as a person with illness? Markers like canes, and diagnoses, and inability to work? Do they mean I am disabled?

Seeing myself as disabled took a long time. It was a gradual process. I still don’t see myself as disabled most days. It was a wearing-in sort of thing, an aging-in that took many years of being sick and living with my illness. Eventually, I realized I wasn’t going to get better, and my illness affected my life to the point that I was just different now than I was before.

Disability didn’t have to be the word for it, although it was the word for it. It was indeed a word I could use for it, and I did qualify for that word. But, I fell in and out of times where I felt I could use disabled as a word for myself, mainly because of the way flares came and went. Sometimes I was better, and sometimes I wasn’t. Sometimes I was in a wheelchair. Sometimes I wasn’t. Sometimes I used a cane, sometimes I didn’t. Sometimes I cooked a chicken roast and danced around the kitchen with my husband. Other times, I was in too much pain. And I wanted to define myself as the “better” me, the one who could do more than the me who was bedbound and couldn’t do as much, or be as many things, as the one who got up in the morning with the energy to vacuum and take on the world.

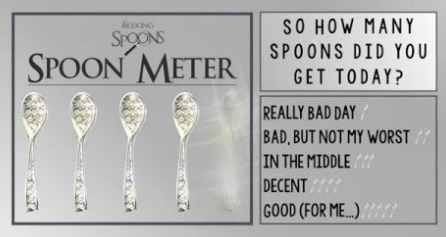

But in time, I learned the spoon theory was a real thing. If I did too much one day, the next day I hurt more. I didn’t have the same body I had before my diagnosis, no matter how hard I tried to get it back, flare or no flare, good times or bad times. Perhaps some months or weeks were just better on the knees than others, and some months, I had more energy than others, and those were a blessing.

After realizing in my heart that this thing called disability was simply something I couldn’t change about myself, I felt bad and was angry with myself, as though there was something wrong with me because of it. But really, there is nothing I can do about it, and the best thing I can do for myself is to accept it. I will be happier with myself if I come to a sense of acceptance with my disability.

This sense of acceptance is hard because with chronic illness, flares come and go, so your sense of disability comes and goes. One day, I can be healthy and feel like I’m not a sick person, and forget that I have a disability. But then it returns, and I am reminded that I’m not as healthy as I thought I was. In fact, it was there all along, just waiting in the background. It was something I always had, healthy days or not.

Other people find it hard to believe I am disabled because I don’t “look sick.” I experience a lot of disbelief from other people about my disability because it is invisible, and because it comes and goes. I’m sure others will be able to relate to this. I am not always ill, and my illness flares and disappears, so I don’t always “seem disabled,” even though it is a real thing and my pain is real too. Some days, even when I look my best, I can be in the most pain, and other days, when I look my worst, I can feel my best. How I look does not determine how I feel. Whether or not I am using a cane does not determine how much pain I am in either. It is frustrating to cope with other people’s beliefs and assumptions about my disability and whether or not it is real, on top of the insecurities I have about myself as a disabled person.

I don’t always define myself as a disabled person. I don’t think it matters if I do or not. In the beginning years of my illness, I let the diagnosis define me, and my life got really small. I have learned that my chronic illness is just a small part of my life. Even on the bad days, when it doesn’t feel like it is just a small part. Even on the days when I can’t hold my toothbrush, or get in and out of the bath properly, or do much at all. These are the days when it feels like that’s all there is to me and it can be hard to get past. But I have learned to live for the moments in between. The happy times in between flares, the good parts of the day when I’m not in pain, and all the time when I don’t have to worry about my health, or what meds to pick up, or what appointment I have next, or what my illness makes me.

When I was first diagnosed with my illness, I thought I would never be able to have a life again. I haven’t gotten some parts of my life back. I may never get some parts back, like a full-time job. But I have a different career than the one I originally had, and I like it much more. I also get to still participate in my old job in different, unique ways, when I can. I’ve designed a life that suits me and it’s adapted to my new abilities. I designed a new life fit to my new skills.

I am married now, to the perfect man, and we just had a healthy little boy. He is absolutely beautiful. And I am a great mom. A mom who plays. I write and spend my time doing hobbies I can do, when I can. On the good days, I enjoy my life, and on the bad days, I rest up for what will come next.

After these many years with the diagnosis, I have made peace with this part of myself — the part that, on some days, is disabled. Even though some days I am well, and others not, the illness or disability still doesn’t go away. I have accepted the fact that my disability is one people often don’t look at and recognize as a disability. I can’t prove it to others, even though sometimes I wish I could prove my pain, because it hurts and is just as real as any other disability.

I have made peace with how it has changed my life.

It’s OK with me.

Because I have a life that makes up for the pain with more happiness and love every day than I could have ever asked for.

I had a great day today, filled with great moments. Now, after having that great day, I am in pain. I’m paying for my great day in illness points. But I live for all the good moments, the ones in between the pain — the laughter, the smiles, the love. I’ve had enough of the good moments today, and for that, I am grateful.