When I was a teen, the concept of suicide was like a dramatic cinema plot, nothing more; something I saw in movies like “Heathers,” or romanticized in stories like “Romeo et Juliette.” To me, suicide seemed as though it was an idea that only fictional characters with tragically scripted lives would ever contemplate. Until, that is, the incomprehensible became a tangible option for me.

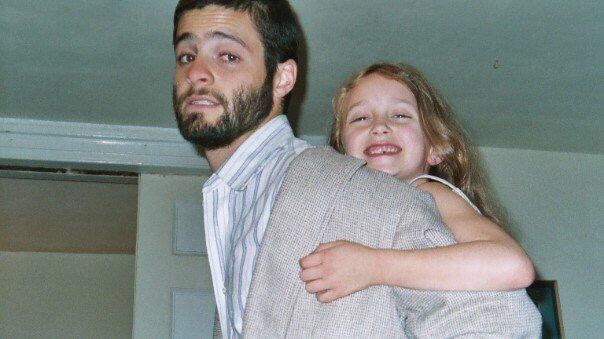

When I was 17, after a sexual assault and not feeling heard by those I went to for help, I attempted to take my own life. I tried to use a very permanent choice to take away a very temporary feeling. My younger brother Jimmy was just 11 years old, and it was his first experience with suicide and the idea of it. Before then it seemed like a far away option. My attempt brought it into focus that day. I believe it sat in his subconscious, and reared its ugly head when he became older and began to struggle mentally. He was vulnerable and was looking for a temporary escape of his own. I thought he was in a phase, we all thought he was just going through a rough time. At 26 years old, my brother, the brilliant guitarist and troubled Yale graduate, “succeeded” with his exit.

This trauma felt like I was in a plane crash. My entire world froze. A thick fog moved in. I became a helicopter mother, wife and friend. No one was going to get sad on my watch. I may have missed my brothers signs, but I for damn sure wasn’t going to miss anyone else. For two years, I made sure everyone within reach was OK — and if they weren’t — I dropped all I was doing to get them to a better mental place. Finally one day my husband said to me, “You can’t save everyone. People are still going to be sad, and some will unfortunately still take their lives. You have to do something with this grief. You can’t keep this up, you need to talk to someone about all of this.” So that’s what I did. I was raised in a family where no one went to counseling. It meant you weren’t strong, it was shamed. But still I went, feeling very skeptical and sure that this woman was not going to be able to help me.

Oh how wrong I was. We spent a month unpacking it all, the assault, the suicide attempt, my troubled childhood, estranged mother, death of my brother, and after all the unpacking, she sat and took pause. She looked at me and said, “We need to take a minute here. You have been through all of these very traumatizing things, and look at how well you are functioning on your own. Look at you. You need to celebrate that. Celebrate what you have overcome and gotten through on your own. You have all you need to do this, I am just going to help you organize it all and give you tools to handle all of the things around you that are so difficult, triggering and hurtful.” One of the first things she encouraged me to do was to find my creativity. Not help my husband (who was a musician) or help our daughter (who was a professional ballerina), but help myself.

So that’s what I did. I started freelance producing, and did some amateur photography on the side. I got a great job at a creative company. And while at that company, we had a teacher/photographer/speaker come to do a talk about her photography project. She was a wounded war vet who was now doing a photo project spotlighting other wounded vets, and telling their stories. She spoke on her traumatic brain injury, about how this project had started to heal her, while in turn healing others. She spoke about how we can all find that event in our lives, to turn it into something to help ourselves process and heal, and in the midst of that work, also help others. As I sat there listening to her, I realized I had to do it. I had to dust off my camera, that I had put down several years earlier to focus on producing, and try to make this project. Fears of having no training, no experience, no training –crept in giving me a huge case of Imposter Syndrome. The veteran photographer, whose name is Stacy, talked me through each doubt and shot them down one by one, showing me that I was simply limiting myself. She then said — when you are ready, your first portrait needs to be of yourself.

You know when you pull the emergency break in a car but you are still kind of moving? That’s how it felt when she said that. It was jarring. So I sat in a studio, alone, for two hour to take my first photo for the project I had named Faces of Fortitude. I sat and talked to myself, asking myself what types of photos made me comfortable. Truth was, I hated photos of myself. So what kind of photos did I want to take of myself, and in turn, of others. Black and White hid my insecurities. Especially when I get upset, I get puffy, red and snotty. I wanted to be hugged by the shadows, I wanted the light to highlight the best parts of me. But I still wanted it to be real, very little to no editing. Just light. I wanted it to be about me, and my emotions, and nothing else. This was my first self portrait.

I put it out onto the internet, Instagram to be exact, and it kind of exploded. I started getting messages from strangers, first a few a day, now seven to 10 a day — of people wanting to share their stories. It was honestly overwhelming. It was so emotional, and at first I didn’t think I could do it. I start to feel the helicoptering happen again, I invested in every person that messaged or emailed me, worrying about their wellbeing. It was then I realized I had no boundaries in place for myself, and my own self-care. So I established the boundaries and vetting process I needed to feel safe, to feel capable of producing the project and staying authentic, while still taking care of my own needs.

The project just celebrated one year in existence this past October 28. In one year I have sat with 100 people (and counting). I have had two northwest gallery shows, and I’ve done my first radio interview and public speaking event. Looking back it’s very daunting, as I didn’t expect it to grow so quickly. I am excited to be working on a book with images from the project as well as poems about grief and mental illness. I started a Patreon and am now trying to take the project full-time. I still can’t get over people that say they are a fan of my work or that I inspire them. The messages that give me fuel to keep going are the ones from people who were feeling alone in their truth, that found safety and community in this project. That is why I do it. I have over 80 people vetted and approved in over 20 cities across the U.S., and now I’m trying to work on a plan to make traveling possible to tell their stories.

This project began as a part of my grieving process, and has taken on a life of its own. I wanted to provide others with a safe space to talk as well as a create a productive channel for myself. I need to show the Faces of the people touched by this epidemic; the ones who are often shadowed or shamed by society. Whether they are suffering a loss, struggling to survive or working to be compassionate to those in the dark — they are all Faces that need to be seen. A part of my heart heals and grows with every story I hear. Everyone grieves and deals with trauma so differently.

I get a lot of people who tell me how heavy this project is, but in truth, it’s so light. It gives me so much light when people trust me enough to share their truths. I feel so much light when people tell me how they have found hope after suicide touched their lives. Their wills to live after their loss or their attempt, they are truly the most beautiful moments of this project. In just one year I have seen the incredible power of the human spirit and I cannot wait to continue to grow, heal and hear more stories and share all of their Faces of Fortitude with the world, so that in hopes we can make a dent on ridding the world of the stigma placed on suicide and mental illness.

One Face at a time.

To see more photos from “Faces of Fortitude,” follow the project on Instagram.

All photos via Mariangela Abeo