The Holocaust Caused Intergenerational Religious Trauma in My Family for Generations

Editor's Note

The following article contains details about the Holocaust, emotional abuse, and religious trauma that may be triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

I’ll be honest. I have started and restarted this article numerous times. Every time I think I have articulated the enduring legacy of intergenerational trauma that has been caused by the Holocaust, I feel as though I haven’t really done the subject justice. It’s daunting to encapsulate how devastating the genocide and enslavement of millions of Jews was by documenting the effects it had upon my own family. I feel a great sense of responsibility to every family who was touched by these atrocities. As such, I approach this article with a sense of urgency to convey the intricacies of how religious trauma is born, festers, evolves, and implodes within a family who never really had the opportunity to resolve it.

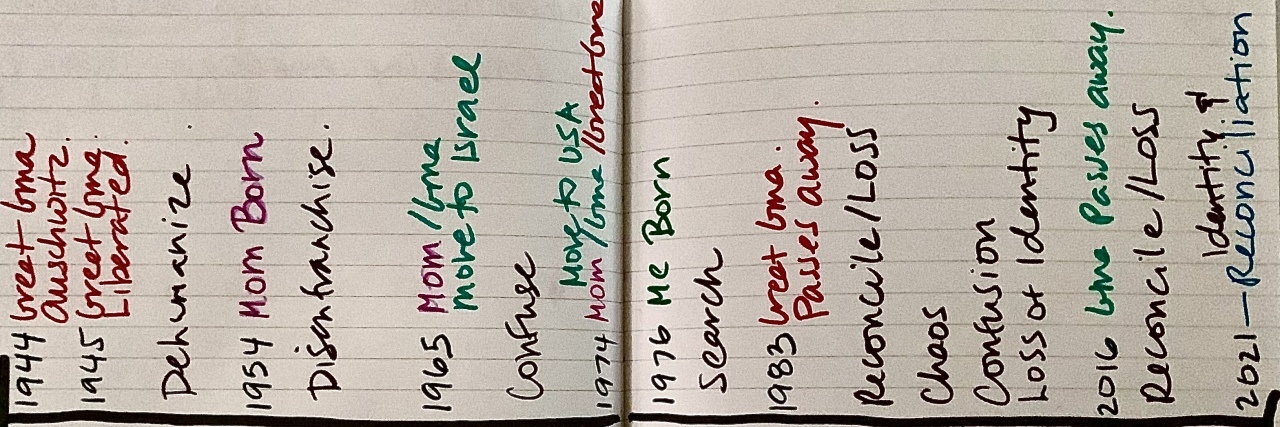

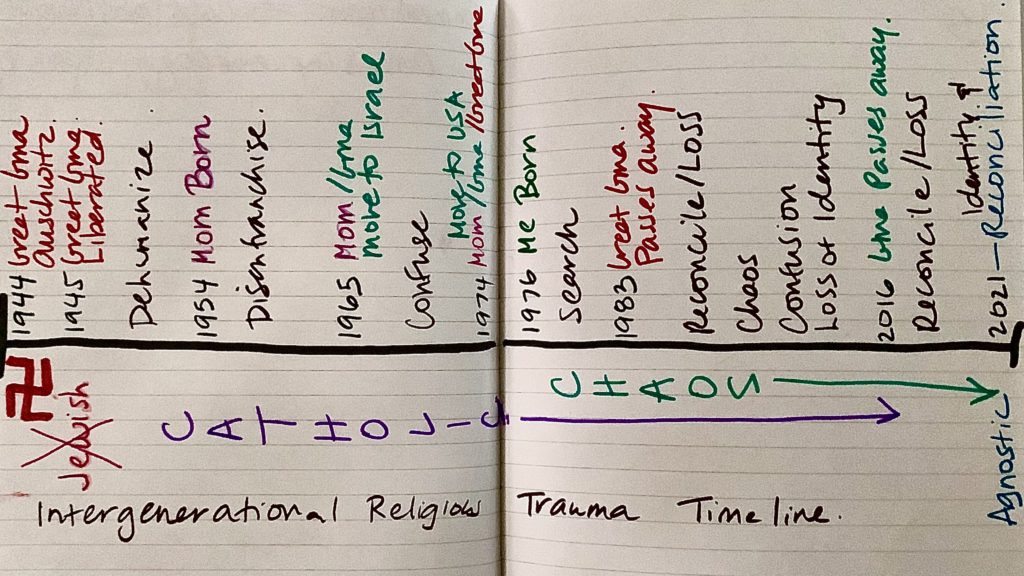

Our story begins in Budapest, Hungary, with my great-grandmother being detained by the Nazis toward the end of 1944 after her husband turned her in. She spent just over a year in the concentration camp at Auschwitz before the war ended and American troops liberated her from the camp. While she survived, she was irreparably marred by the experience. Her identity as a Jew made her a target for extermination and as a result, she instilled within my grandmother an urgency to disavow her Jewish heritage and to fully embrace her identity as a devout Catholic. This kind of shift is not uncommon amongst survivors of the Holocaust. They knew that if it could happen once, it could happen again, so they hid their heritage and adopted new ones, in a sense erasing who they were to protect future generations.

If you had met my grandmother, you would never have known that she was Jewish. She had been baptized Catholic as a child and after witnessing what her mother had lived through, she spent the rest of her life as a devout Catholic. For as long as I can remember she carried numerous photos of Jesus in her purse, ended her prayers gesturing the sign of the cross, and seemed to believe in a traditional Catholic worldview of heaven and hell, although she never went to church. While initially, she was adamantly against cremation — something I thought had to do with her Catholic belief system — toward the end of her life, I recall having discussions about the logistics of transporting her body from Illinois (where we lived) to California, where her burial plot existed. When we finally settled on cremation, the only thing she kept saying was that she was afraid she wouldn’t be fully dead when they cremated her and she’d feel like the Jews who were incinerated during the Holocaust. My logical brain at the time didn’t recognize how much of a trauma response this was for her. I just needed to settle her final wishes in her will. In hindsight, that was a powerfully telling moment of how what her mother endured remained with my grandmother until her death.

My mother’s religious leanings were… chaotic, to put it mildly. She was born in Budapest, Hungary in the 1950s to my Catholic grandmother and a Jewish father who abandoned her at a young age. As a young child, she was socialized to be Catholic but moved to Israel when she was 11 and lived there until coming to the United States when she was 20. Her entire time in Israel revolved around a rediscovered sense of her Jewish identity, if not in a religious sense per se, most definitely in a cultural sense. I think this ambiguity in childhood combined with the abandonment of her father and the constant retelling of the horrors of the Holocaust by my great grandmother left her with a sense of both fear of and longing for some kind of religious community to belong to.

I was born only a couple of years after my mother, grandmother and great-grandmother all immigrated. While they were surrounded by other Hungarians in the Los Angeles area of Southern California, they still did not belong to any specific church or religious group. Growing up, I was acutely aware of dichotomous rules within our household of four generations of women; on the one hand, my great grandmother and grandmother never discussed their religious beliefs openly; on the other hand, my mother appeared almost obsessed with exploring various religions and belief systems. In hindsight, I recognize that as a result of her childhood trauma and undiagnosed mental illness, she became vulnerable to coercion by anyone who made her feel special. Slowly she wove a patchwork religion quilt made up of snippets of Catholicism and Judaism mixed together with concepts from Hinduism and Buddhism. These got even more muddled with a kind of “New Age” hodgepodge of beliefs and rituals that even as a child, I found very disjointed and confusing.

One day we would visit an empty church where she would pray for what seemed like hours while I lit candles and played with the holy water. The next, we would attend services at a yoga center, where the grown-ups would chant and worship a kindly looking bearded guru and meditate while the children were separated and taught about all different religious practices… something which, in hindsight, gave me a bit of a cult-like vibe.

Then, my mother went through a phase where she insisted that she was in direct communication with the spirit of the famous composer Johann Sebastian Bach and that he was communicating through her. She’d spend hours writing nonsensical things, seemingly possessed, while my uncle and grandmother pretended that everything was “normal.” Frankly, I found this behavior terrifying and by this point, I had learned to placate whatever flavor-of-the-month religious practice my mother had settled on just to make her happy. This segued to an obsession with reincarnation, crystals, tarot cards, and visiting fortune tellers.

By the time I was in high school, I was perfectly clear that it was my job to go along with whatever my mother believed because her identity came as much from whatever she identified with as it did from my reflecting those beliefs back to her, a symptom of how dysfunctionally enmeshed our relationship was. If I even hinted at not believing something she did she would accuse me of being brainwashed by school, friends, and eventually my husband because obviously, I couldn’t possibly decide on my own that her beliefs were flawed — that would conflict with her image of herself as the perfect mother.

It wasn’t until she started drawing crosses on my forehead with her thumb, praying that I would be returned to her safely anytime I left the house, that I really began feeling alarmed and disturbed. The second I was no longer near her, I’d frantically try to wipe the cross off my forehead like it was some kind of curse, rubbing and scratching until I literally broke the skin. The whole thing felt violating, illogical, and completely unnecessary. I couldn’t wait to go off to college, get married, and no longer be steeped in what felt like a version of hell on earth. In her desperation to find meaning in life, my mother created an environment within which I couldn’t reconcile religion of any kind as being logical, useful, or necessary to my existence. I had met more people who were nonreligious and behaved morally because they saw it as their responsibility as a human being to do so than I had ever met in any of the religious or pseudo-religious groups we sampled throughout my childhood.

Now that I am no longer bound to my mother by some kind of invisible umbilical cord, I can see how traumatic that upbringing was and how the chaos of her religious beliefs translated to my complete rejection of religion altogether. While I wholeheartedly respect those who find meaning within faith, it’s something that I know in my gut has caused nothing but pain to my family for four generations. What I know unequivocally is that religious persecution creates immeasurable loss and pain at a psychic level. The dignity that my great grandmother lost by being dehumanized led to a coerced submission to an identity based on fear within my grandmother and a complete loss of identity fueled by angst and disenfranchisement within my mother. With me, it came full circle.

Through my own healing journey, I am taking the torn shreds of the tapestry of the religious trauma of four generations of women and reweaving them into a new, more grounded sense of humanity and belonging built on interpersonal relationships that are not bound within any kind of divinity or religious dogma. As this poignant Stephi Wagner quote states, “Pain travels through families until someone is ready to feel it,” and I am ready to feel it and end it in honor of not just my own family but of all of those who have been affected by the Holocaust.