For Rob, everything seemed normal at first. As a firefighter, some of his initial post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms actually helped him perform his job well. “Some of the symptoms that go along with PTSD actually help you do your job. For example, one of the big symptoms is hyper-vigilance, where you’re on guard for everything,” he explains. “That’s trained into us. You go to a car accident on the highway, and if you’re not hyper-vigilant, that can get you killed.”

Another example is emotional numbing, a PTSD symptom, but also an asset for firefighters when facing an emotional situation. “If you’re doing CPR on an infant that’s VSA [vital signs absent] and actually felt the feelings of the parents, you wouldn’t be able to do your job.”

Rob wrote off much of his emotional experiences and reactions as “normal” according to the life of a firefighter. Much of it was something to be accepted as part of the job, something to just brush off and move on from. His ego often got in the way, convincing him what he was experiencing was “no big deal.” When you’re running into burning buildings all the time, it’s easy to let the ego take over and convince you that anything else should be easy to handle.

Then a simple memo from his deputy chief in November 2018 changed everything. Rob lost it upon receiving the memo, and he started having more and more angry outbursts at work. And rather than letting the anger go away after time passed, Rob kept ruminating in his feelings. He felt unable to identify why such a small memo set him off. He got into disagreements with his wife, where he would explode with angry outbursts. Then, 20 minutes later, it would feel as if nothing had happened. That’s when he started to realize something was really off.

At the time, Rob did not realize that it wasn’t just the memo causing him so much unexplained grief; it was all of the traumatic calls leading up to that memo. “My day-to-day life was filled with anger, frustration, emotional outbursts, flashbacks. My wife was getting ready to leave me. Fortunately, in my case, I don’t drink, so substance abuse wasn’t an issue. But that’s what life was like in my day-to-day life. My life was absolutely falling apart. And I had no idea why.”

In April 2019, after months of dealing with those extreme emotions, Rob sat down with his wife and told her he needed help. “There wasn’t one specific switch going off [saying I had PTSD]. It accumulates, at least for complex PTSD, which a lot of first responders suffer from. It’s not one specific bad call; it’s all the calls.”

Rob reached out to someone on his department’s peer support team, and he was connected with the trauma center. He considers himself lucky to have had this resource available as a firefighter, knowing that many people do not. Rob also connected with the first psychotherapist he worked with, another rarity for many who often go through dozens before finding a right fit. “My diagnosis was severe PTSD, severe major depressive disorder and borderline OCD. When I was given that diagnosis, I was actually completely shocked,” he says. “What I thought depression looked like, it really wasn’t. But almost always, when you’re diagnosed with PTSD, you’re also diagnosed with depression, because there’s such an overlap of symptoms.”

After starting therapy sessions while continuing to work, Rob realized he needed to take some time off to truly dedicate himself to healing. When he told his crew what was going on, he discovered that some of his team members noticed a change in him years prior, and they wrote it off as him being a “grumpy old man close to retirement.” Not only was his crew also in denial about what was actually going on, but they also simply did not recognize the symptoms of PTSD and depression. This was the first time Rob realized more needed to be done in terms of PTSD education among first responders. He knew part of his recovery would be sharing his story.

“One thing I say all the time [to other departments] is, ‘You can’t walk through water and not get wet. You can’t walk through a sewer and not come out [smelling]. And you can’t be a first responder, doing the things that we do, seeing the things that we see, experiencing things that we experience, and not be affected.’ And there’s no shame in that.”

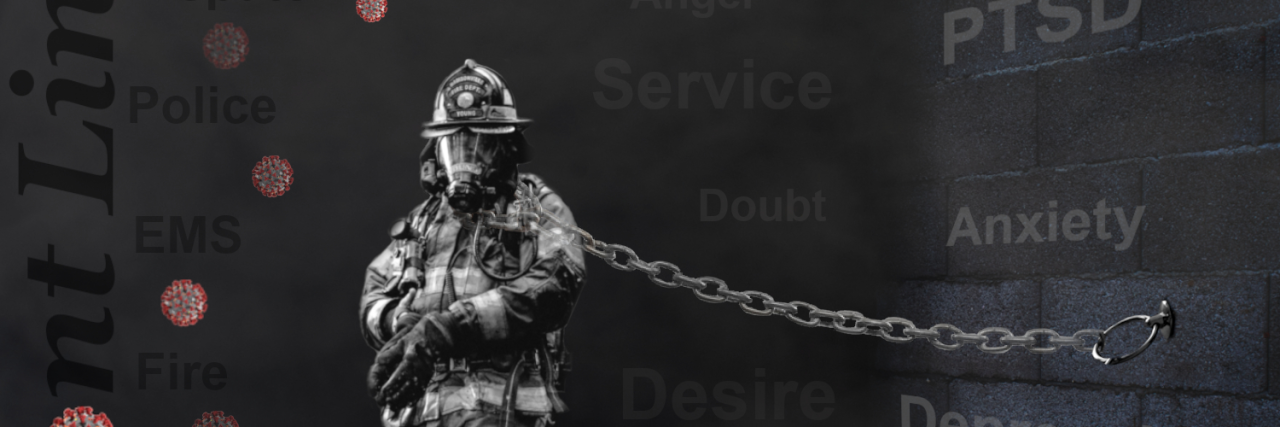

A common misconception is that PTSD only affects the military, when in fact, it also impacts first responders at very similar rates. It’s not about just talking about the bad memories that build up to cause a PTSD diagnosis; it’s also about fixing the person that’s been changed and helping them trust their team and themselves again. For Rob, letting go of the ego that many first responders develop is key in allowing yourself to admit you need help and accepting that help.

When it came to Rob’s own treatment, it wasn’t as simple as just therapy and advocacy. Rob was open-minded to many different types of treatment; if it worked, he kept it, and if it didn’t, he moved on. Things like yoga, meditation, journaling, digital artwork, gardening, aromatherapy, EMDR therapy, equine therapy and peer support have all been parts of his recovery over the last two years. He’s currently participating in a clinical trial, which he calls “goal-management therapy,” something used to assist people with cognitive decline…and now people living with PTSD as well. “What a lot of people don’t realize about PTSD is that it’s not just a psychological issue. More and more brain imaging studies show that there are actually physical changes that go on in your brain.”

Today, Rob’s support team comprises him, his psychotherapist, an equine therapist and an occupational therapist to help process the traumatic memories and deal with some of the more problematic symptoms like hyper-vigiliance and situations or geographical triggers that cause emotional distress. PTSD is a complex issue, so it takes a complex process for everyone to heal, not just the individual. Spouses can develop vicarious trauma from living with somebody with PTSD, so one of the first things Rob did was help his wife get therapy as well. “We’ve given both [of our therapists] permission to share information. It’s helped a lot. We watch Facebook Lives together that deal with PTSD. So she’s got a better understanding of what’s going on in me up there. And it’s helped her because she realizes it’s not about her.”

Healing from PTSD has also afforded Rob’s adult children an opportunity to know who their “real dad” is, after years of witnessing the pain-stricken father who never seemed himself. And while it’s hard to be open and honest about suicide ideation and other struggles with his family, Rob believes it’s important to talk about mental health, more than anything. He’s now working toward being trained as a peer support person and hopes to help other departments, particularly ones in more rural areas that may not have the same resources. He wanted others struggling with PTSD to know that it does not have to be a life sentence. Some symptoms may stick around for a long time, but they are manageable, even if it does not happen overnight.

After realizing his own crew did not recognize his anger as PTSD, Rob says knowing your own symptoms is most important when you’re first diagnosed with PTSD. “I tell people that you need to know what the symptoms are, and you need to look after yourself,” he says. Once you learn what those are, it’s easier to move toward managing them and not allowing PTSD to take over your life. “[I try to instill] hope, because when you don’t have hope, that leads to dark places. You can still thrive when you have a mental health condition.” As Rob says, it’s only a life sentence if you let it, so don’t let it.