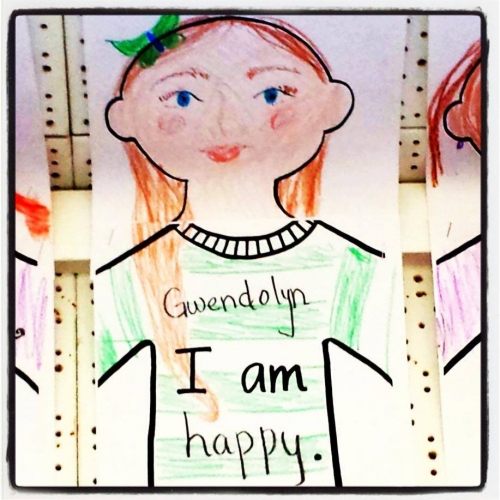

Gwendolyn drew this.

It was her first grade self-portrait. She chose to include her bipap, her butterfly bow, her long hair and a striped shirt. She also chose the words, “I am happy.” This was all Gwendolyn. No guiding or pushing in this direction. Other kids chose things like “I am a sister.” or “I am 6” or “I am tall.” No other child wrote simply, “I am happy.” To us, it was profound. And validating. And so very Gwendolyn.

Since her death, well-meaning people often say, “Now she is no longer in pain” or “Now her suffering is over.” But these expressions do not resonate with Gwendolyn’s life. Yes, of course, spinal muscular atrophy does cause hardship and Gwendolyn faced many, many challenges. But, she was happy. She woke up every day, not in pain, but with enthusiasm for what fun the day would bring. She went to bed each night, not suffering from her life, but with joy for what she got to experience that day. Even on hard days. And up until the last few weeks of her life.

I get it, we tell ourselves and each other these things to bring comfort to the living — to those suffering here on earth after the person they love so dearly dies. And, in some cases, these expressions hold true. But I also think they get a liberal sweeping across anyone with disabilities. And, these simple words, though well-intentioned, carry power in creating ableism. In fact, in some cases, these expressions hold a sentiment that the death of a child with disabilities is somehow less devastating because they were not typically abled.

Gwendolyn’s life was complicated, certainly, but it was also what she always knew. She was so very proud and confident and certain of her self-worth. I’m not saying she was never frustrated by her disabilities or medical complications. She was at times, and those were the hardest conversations I’ve ever had. But, then as children do, she dusted off and moved on to something else. I’m also not pretending there was never any pain or suffering. There were traumas she had to endure that will haunt me forever. And, yet, she was still happy and it doesn’t sit well to define Gwendolyn’s life after she’s gone in a way that simply wasn’t how she saw herself. These expressions also make my Dragon Mom spine rankle, protective of all the many children I know with disabilities who also love their lives and live with joy and exuberance — even with all the many struggles they must face.

This has needled me since Gwendolyn’s passing, but is especially on my heart as my younger daughter, Gwendolyn’s little sister, Eleanora, asks more questions. My husband and I are very sensitive in how we talk to Eleanora (or any child) about Gwendolyn and why she died, specifically because of the ableism that often frames people with disabilities are somehow less than on earth because of their struggles. That isn’t what we believe. And that isn’t how we want our children to view their sister or others with disabilities. Our hope is they will embrace all differences with acceptance. I don’t expect them to not notice. Children are astute and curious. But I do hope when they see a child in a wheelchair (or with any difference for that matter), their first thought has nothing to do with pain or suffering or pity. Instead, I hope they simply wonder what that child likes and if they can play together.

At 4-years-old now, questions about Gwendolyn’s death have started with frequency, and while we are still navigating our way, I know with certainty we will never, ever say: “She was in pain and suffered.” Instead, we will tell her the truth:

Gwendolyn was born with a disease that made her muscles weak and eventually they got too weak for her to keep up. But she was happy and loved life and we miss her every day.

A version of this post first published at theGSF.org blog.