With Opioid Overdoses on the Rise, How Do We Know People Die by Suicide?

Editor's Note

If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

If you or a loved one is affected by addiction, the following post could be triggering. You can contact SAMHSA’s hotline at 1-800-662-4357.

Some of the most powerful mental health advocates, Jolissa Hebard included, come from lived experience. She knows firsthand how complicated suicide and drug overdose prevention can be. Her son Ethan is a suicide attempt survivor, and one of her sisters died from a drug overdose that involved opioids. Hebard has also worked through her own mental health issues and addiction.

Hebard now works to shed light on topics such as suicide warning signs that aren’t so easy to spot. While her son’s attempt was clearly suicide, in her sister’s case, the loss isn’t so clear. Her sister struggled with addiction but had been OK for a while. When she died from a drug overdose, Hebard’s sister’s son and daughter believed it was a suicide but Herbard didn’t think so.

“It’s not like with my son. We knew. It never would have made sense to us but he wrote a note. But with my sister, it was like, ‘What happened?’” Hebard told The Mighty. “I don’t believe that my sister would have taken her life on purpose. I just don’t see that about her. I will never know, we can never know. And that not knowing is so frustrating.”

Opioid Use, Overdose and Suicide

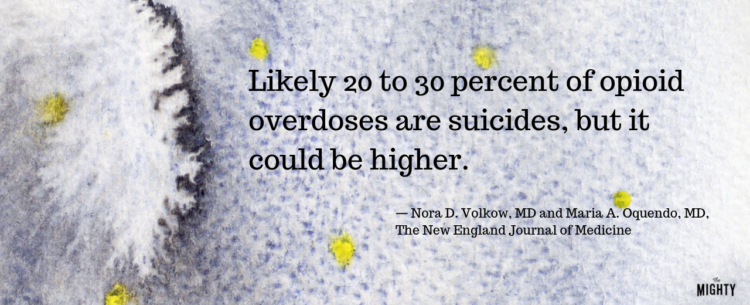

Not knowing is a painful reality for suicide and overdose loss survivors, and it’s one Drs. Nora D. Volkow, M.D., and Maria A. Oquendo, M.D., have taken a closer look at in an op-ed published in The New England Journal of Medicine in April 2018. In the face of the opioid epidemic, they looked closer at the question, “How do we know people die by suicide?”

In the case of opioid overdoses, the answer is not straightforward. It’s likely we are significantly undercounting the suicide rate among opioids overdose deaths. Despite lower estimates, 20 to 30 percent of opioid overdoses are likely suicides, and it could be higher. The implications of not having accurate information mean we could be missing opportunities to match more people with the support they need.

“Interventions to prevent overdose deaths in suicidal people will differ from interventions targeted at accidental overdoses,” Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, told The Mighty. “Yet most strategies for reducing opioid-overdose deaths do not include screening for suicide risk, nor do they address the need to tailor interventions for suicidal individuals.”

Why We Don’t Have Good Information

Part of the issue with parsing out the data on opioid overdose-related suicides is how the cause of death is determined. Medical examiners and coroners only have past information to go on, like medical records, interviews with loved ones and, in the case of suicide, clear signs of intent such as leaving a note. Based on their investigation, medical examiners then determine a death that’s not due to natural causes as accidental or “unintentional,” suicide or “intentional,” or undetermined.

There is no standard method for determining cause of death nationwide, so reporting varies from state to state. However, one study found that in general, suicide seems to be underreported across the board. This study’s authors hypothesized the stigma of suicide made some medical examiners less likely to rule a death a suicide, especially if they lack “concrete” evidence like a suicide note. These deaths are then classified as accidental or undetermined.

For suicide prevention advocates, it’s not surprising that determining a cause of death is difficult. Suicide is complicated and multifaceted. Not everyone outwardly expresses suicidal thinking or the “typical” warning signs. Many people never come in contact with the mental health system or others who could help. Some people experience passive suicidal ideation, one big factor in why it’s so hard to accurately determine opioid-related suicides.

Passive Suicidal Ideation

Passive suicidal ideation is when you don’t have an active plan to attempt suicide but you still feel like you don’t want to be alive. You may have suicidal thoughts and you’re not going to do anything about them, but if you didn’t wake up tomorrow, that would be OK. Passive suicidal thoughts can also show up as other risky behaviors, including things like dangerous driving, putting yourself in unsafe situations or drug use.

“I didn’t know about passive suicide,” said Hebard. “I didn’t realize that instead of actively seeking a method to kill myself, I started having unprotected sex and using drugs and drinking … thinking, ‘Oh, well, if I happen to die, it’s just my time,’ which is another whole form of suicide that I don’t think is talked about very often.”

!["We need to get rid of the shame of talking about [suicide] and the fear of talking about it." — Jolissa Hebard, mental health advocate](https://themighty.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Ask-people-very-specifically-about-their-suicidal-thoughts-and-not-Are-you-suicidal-or-not_-but-What-thoughts-do-you-have-about-your-future__-2-750x305.jpg)

Passive suicide risk is often missed on traditional risk assessments that ask whether or not you have a plan. And it’s missed when medical examiners make a cause of death consideration — likely because it’s difficult to be certain about intention and complex to measure when we look at opioid overdoses in particular.

“One of the challenges in suicide is that there’s actually a range of suicidal behavior,” said Brian Hurley, M.D., M.B.A, DFASAM, a psychiatrist at the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services and treasurer of the American Society of Addiction Medicine. “People that might have passive suicidal ideation might not care if they stopped breathing after they took a heavy dose of opioids. And does that count as a suicide attempt?”

While it makes sense to connect people with active suicidal thoughts and a plan with immediate resources, for those who have a co-existing opioid addiction, passive suicidal thoughts can be an equally major risk factor for harm. Suicidal thoughts may show up differently, but that doesn’t make them less painful, difficult or dangerous when combined with opioid use.

“We know that people use things like opiates because of the pain that they’re going through. It could be physical pain or it could be emotional pain,” Julie Goldstein Grumet, Ph.D., director of Health and Behavioral Health Initiatives, Education Development Center and director of the Zero Suicide Institute, told The Mighty. “We do know that, fundamentally, when people are using opiates, they know the risk that they’re taking. Certainly a Russian roulette, and there’s a certain comfort with that Russian roulette.”

Why Opioids?

With opioids, in particular, the rates of overdose deaths has risen considerably. According to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 68 percent of drug overdose deaths involved an opioid, which is six times higher than in 1999. Much of this dramatic increase can be tied to fentanyl and the particularly potent nature of opioids in general.

“What’s tricky is that opioids have what in the technical terms is a ‘narrow therapeutic window.’ That is the difference between the dose that people take to alleviate pain, the dose that people take to get high and then the dose that kills you,” Hurley said. “Those doses aren’t terribly different from each other.”

Opioid use in itself is also a risk factor for suicidal thoughts and attempts. According to data cited in Volkow’s op-ed, those who use opioids regularly were “75 percent more likely to make suicide plans and twice as likely to attempt suicide as people who did not report any opioid use.” There’s also a large overlap between drug use and mental health conditions, where substances can serve as self-medication.

“We know about 40 percent of active drug users also have a mental health problem, so that’s increased their risk for suicide already,” said Goldstein Grumet. “A lot of people, though, were never diagnosed and they’re never getting help for their mental health problem.”

Taken together, passive suicidal ideation, the danger of risky opioid use and unknown underlying mental health risk factors, many suicides may be going undetected. If we want to have an impact on suicide and opioid overdose death rates, we need to focus our efforts on those who live in this grey zone of risk before it’s left to a coroner to determine their cause of death.

Focus on Suicide Assessments

One strategy for better determining who is at risk for suicide is adjusting how and where we conduct suicide risk assessments.

“There is a need to develop and validate better screening tools to help characterize suicide risk along a continuum of awareness regarding suicidal intent,” Volkow said. One way we can do this is to adjust our suicide risk assessment strategies to a “future-oriented” approach.

“Ask people very specifically about their suicidal thoughts and not, ‘Are you suicidal or not?’ but ‘What thoughts do you have about your future?’” said Hurley. “In a comprehensive suicide assessment, you can actually get a narrative from somebody about how they see themselves in their lives and their intention for the future, their thoughts of dying and their thoughts of living.”

Suicide assessments also need to be implemented at all levels of the health care system to capture more people who never seek out mental health or addiction services. According to Goldstein Grumet, if the larger health care community, like family doctors and hospitals, started doing regular suicide risk assessments, we may be able to connect more at-risk people with the resources they need.

What You Can Do

You can also bring your suicide prevention efforts even closer to home and your loved ones. How? “Talk about it,” said Hebard.

“We need to talk about it more,” she continued. “Let people know that there’s no shame in thinking about killing yourself. There’s no shame in having someone that you love die by suicide. … We need to get rid of the shame of talking about it and the fear of talking about it.”

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources. If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, the Trevor Project at 1-866-488-7386 or reach the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

Header image via Benjavisa/Getty Images