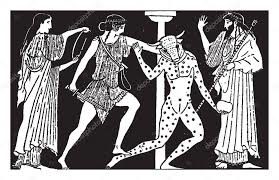

Why Healing From Childhood Trauma Can Feel Like ‘Slaying the Minotaur’

Editor's Note

If you have experienced emotional abuse, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

Twenty-five years ago, I found myself on a secluded Cycladic island famous for a shrine to the Virgin Mary where many pilgrims would come crawling almost a quarter mile from the port on hands and knees to have their prayers heard. A fresh young thing out of college at 20 years old, I had landed a job as an English instructor by chance while sharing a taxi in Athens with the owner of the language school desperate to hire a native speaker to save his business and its reputation. The teacher he had hired, a native Greek, wanted to sabotage any success the students had of passing their English exams as a ploy to drive his boss out of business and then open his own school. I took the job not because I needed it; I had been teaching already as an adjunct for an American University in Athens.

I took the job to escape the Minotaur. My entire life up to that point had been a series of escape plans. My father, the Minotaur as we used to call him, slammed fists on objects and persons, threw chairs, roared at a deafening pitch, whipped puppies, kept us awake at night during his fits and mad ragings. He terrorized us. We tried to grow up in the intervals he was not at home, when he was at work, at the park, the weekly run at the supermarket. He kept my sister and I trapped in a roach-infested railroad apartment in NYC like some tragic mythic princesses in a tower. We did everything we could not to tick him off, but his moods were so unpredictable. You could be doing everything right and then boom, he’d explode.

We got through our childhood like soldiers crawling through a minefield dodging hidden booby traps that might detonate his rage — don’t crinkle plastic bags, make sure to place a glass of cold water within his arm’s reach at dinner, don’t talk above a whisper and certainly when we was talking or rather yelling, don’t give anybody your phone number or tell them your business; outsiders were not to be trusted. I never grew up like a “normal” teenager. It was like I had to hide the fact that I was living with a monster, half-human, half-raging bull. I had no friends. I had to live with the dark secret that even though we looked “normal” — we got straight A’s, went to work, seemed friendly enough — we lived our days in terror trying to appease the Minotaur.

If we weren’t careful, he would eat us alive.

Later in college while taking an Abnormal Psych class, I realized that my father was the Minotaur because of a thing called bipolar disorder. The textbook definition outlined his behavior perfectly: “rapid periods of mood change alternating between aggressive rage and lethargy.” While the diagnosis took the mystery away from his erratic behavior, it did nothing to help a lonely social misfit cope with the terror of hiding a “monster.”

So I did the only thing I could do — escape. I rushed to finish high school, skipping a grade and taking a heavy course load of AP exams and other college credit bearing classes to graduate at 16. I rushed through college, asking special permission of the Dean to register for 21 credits instead of the usual 12 or 15 other undergrads took. As a result, I graduated with a B.A. at 19. I wanted a career in teaching, and I wasn’t going to sacrifice an education by leaving home for a series of low-paying jobs. My classmates thought I was either “crazy” or a genius. They never knew the truth — I was trying to escape a monster.

But, my patriarchal Greek culture did not make this easy. Greek culture, although it encourages girls to get an education, expects them to be obedient. It is unheard of for a young girl to leave home and live on her own, especially for parents of that generation. This would be equivalent to spitting at them and saying, “Fuck you! I’m going to move out so I can be a whore.” No respectable girl moves out of mamma and baba’s house except to get married. So how did I get out of this situation? I convinced them that it would be easier to find a job if I moved back to their home country. I graduated around the time of the recession in the early 90’s. They reluctantly agreed, only because I would be under the watchful eye of relatives (it is not uncommon for different branches of a Greek family to occupy an entire building with aunts uncles and assorted cousins living on each floor).

And this is what I did. It was good for a while. I was finally in the clear. For me it wasn’t about partying hard and living it up. It was about straight up survival. I needed the peace and the space to get to know my own soul. I was only looking for peace. I got a job teaching English at a university and set up a lucrative side gig of private lessons. But three months later, to my utter horror, there he was, the Minotaur at my doorstep. He had come to find me, to make sure I was “safe;” the same way he stood sentinel outside the women’s restroom to make sure no one would bother us. It was a nightmare. I had tried so hard to escape and now I had to find another escape route.

That’s when that job on the remote Cycladic island came as a godsend. He couldn’t follow me there.

He came for a week to see if I had set myself up properly and eventually he left. I had escaped again. I was never that religious, especially not to the patriarchal religion I had grown up with, but on that island, sacred to the Great Mother, something started to happen to me.

I was alone for the first time for a long time. In the quiet of my studio apartment overlooking the azure Aegean, threads of memory would materialize as I made my morning coffee before work: the time he slapped me in the street when I was in middle school because he couldn’t figure out something on an official court document; the time he woke us up 10 past midnight until twenty past two to lecture us about how to do dishes and keep the body clean; the time he had ripped all my Led Zeppelin posters from my basement hideaway, the ones I had scrimped and saved for.

I was processing trauma. I was groping my way through the labyrinth of so many years of unprocessed pain. Under the gentle gaze of the Virgin, the great Earth Mother, who had borne so much emotional pain, I started to heal. Eventually, I left the island for lands farther away — Heidelberg, London, Barcelona — totally out of the Minotaur ‘s grasp. He was never able to control me again. I made my own way through the world.

Physically at least. That’s the bittersweet ending to the story. Even though I managed to escape the Minotaur’s labyrinth, I did not slay him. I carried him in me for years after that. I have been trying to escape an entire lifetime. This is what I have learned these things: escape works as a survival plan up to a point. To slay the Minotaurs in your life, you need to really face them straight on. It’s hard to get rid of the monsters just by growing up. You wind up marrying them or acting out the same way you did when you were a child.

To heal the trauma of childhood abuse, no matter what the cause intentional or not, you must face the monster. You have to get help, an ally, a guide, someone who can build your courage, your faith in yourself; a goddess who can guide your sword into the heart of the beast and protect you under her aegis.

That goddess could come in the guise of a friend, a classmate, even a writer of a feminist blog. The important thing is that you must slay your own Minotaur and make peace with it in order to become a hero. Take heart; you can.

To sign up for expressive arts classes with Irene, the slayer of her inner Minotaur, log onto www.greekamericangirl.com or www.hellenicartsforhealing.com

Getty image via MatiasEnElMundo.