We Tell Suicidal People to 'Get Help.' But What Happens When They Do?

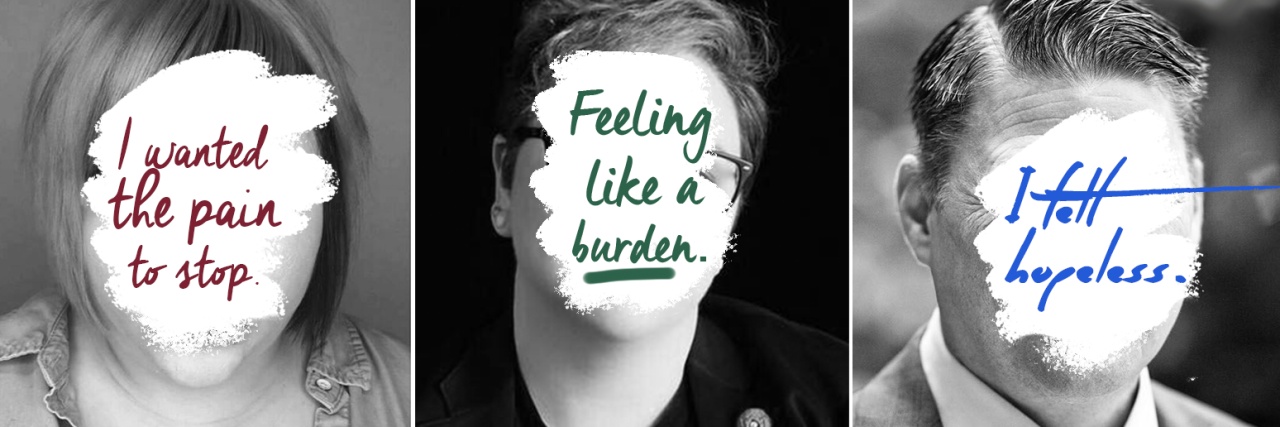

In this Mighty Feature, we’re asking hard questions:

Why is the suicide rate rising? What happens when people reach out for help? What can we do to save lives?

Through surveying and interviewing our community’s suicide attempt survivors, as well as speaking to mental health professionals, we attempt to find some answers.

Editor's Note

If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

Towards the end, Marlin Collingwood asked his husband, Gary, the same three questions every Sunday night — the ones you’re supposed to ask when you’re afraid a loved one might be suicidal.

Are you feeling suicidal?

Do you have a plan?

Do you have the means?

The answer to the first question was almost always yes. The answer to the second question was sometimes yes, sometimes no. The answer to the third question though, was always no. He didn’t have the means to kill himself, which meant, for now, he was safe.

Except one night, Gary lied. When Collingwood came home from work early on Monday, May 5, 2014, he found a note taped to his front door.

Gary had killed himself and didn’t want Collingwood to find him.

Often when someone dies by suicide, we wonder why they didn’t reach out. We shake our fists at the stigma surrounding mental illness, claiming that without it, our loved ones might still be alive.

To combat this, we spread suicide prevention awareness — spanning from letting people know suicidal thoughts aren’t shameful to spreading information about suicide warning signs. Every September, during National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, hashtags and campaigns make their way across the internet encouraging people to get help, telling people to reach out.

This awareness work is important. Telling people to get help when they’re suicidal is important.

But there are less talked about, more complicated parts of preventing suicide that don’t sound as catchy on a T-shirt. And when people like Gary (or Chester, or Amy, or Scott) die — people who were receiving “help,” who were open about their experiences — it exposes an uncomfortable truth:

There’s still so much we don’t know about preventing suicide and not a lot of proof that what we have been doing works.

There were so many unique things about Gary’s life. But one of the unique things about his struggle with depression was that he literally, to the best of his ability through the goggles of depression, did everything he was told to do.

“There were so many unique things about Gary’s life,” Collingwood said. “But one of the unique things about his struggle with depression was that he literally, to the best of his ability through the goggles of depression, did everything he was told to do.”

The suicide rate has been increasing steadily since 1999, and from 2015 to 2016, the most recent available data, it rose 1.2 percent. Despite this, and despite that it is currently the 10th leading cause of death among adults in the United States, suicide prevention funding doesn’t compare to money spent fighting other leading causes of death. On a list of research areas funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), suicide prevention is 206 on a list of 285 research areas, sorted from most-funded to least.

Increased awareness without growing research to support our go-to interventions leaves those who dedicate their lives to suicide prevention in a difficult position. From suicide risk assessment to hospitalization, the messages people receive from the mental health system aren’t always as hopeful as suicide awareness campaigns imply.

To reduce the suicide rate, we can’t just keep telling people to get help. We need to start having honest conversations about what kind of help is on the other side.

A System of Hopelessness

When Jess Stohlmann-Rainey tried to kill herself in the bathroom at her high school’s gym, she told her gym teacher, who called the police, who escorted her to the guidance counselor’s office. The guidance counselor accused her of acting out for attention and said the attempt wasn’t “serious enough.”

She was then suspended for bringing a knife to school. Her mom picked her up and brought her to a psychiatric hospital where she stayed for about 10 days.

All I learned in treatment was how to act ‘less crazy’ than the other people there in order to get out. I didn’t get better at all.

Those who’ve been admitted to a psychiatric hospital while suicidal know the drill. No shoelaces. No strings on sweatshirts. Sometimes a strip search upon admission. Supervised showers and 15-minute interval room checks.

Despite all the measures to keep patients safe, Stohlmann-Rainey’s roommate killed herself during her hospital stay. Stohlmann-Rainey was the one who found her.

“While we’re systemically implementing these systems that are supposed to be about safety, it’s a) not working and b) making people feel worse,” Stohlmann-Rainey said. “All I learned in treatment was how to act ‘less crazy’ than the other people there in order to get out. I didn’t get better at all.”

There are a few ways someone who is suicidal might end up in a psychiatric hospital. For those who attempt suicide and live, they may be transferred by way of the emergency room after receiving any necessary medical care. Some, without other options, might bring themselves to the emergency room. Whether ER staff are trained for (or compassionate towards) people who are suicidal varies. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, two out of five people who went to the emergency room for a psychiatric emergency rated their experience as “Bad” or “Very Bad.”

In an online survey of more than 1,700 ER doctors, presented at the 2016 American College of Emergency Physicians conference, more than seven in 10 reported that on their last shift, psychiatric patients were still waiting for an inpatient bed. Of those doctors, more than a third say the psychiatric patients had to wait at least two days for a bed to become available.

Others may end up in a psychiatric hospital because a concerned friend or mental health professional steps in. In a survey conducted by The Mighty of 1,622 suicide attempt survivors, 50 percent of people were hospitalized after their last suicide attempt, and of those, 78 percent entered the hospital voluntarily.

Involuntary hospitalization happens when a mental health professional deems someone a danger to themselves or others — whether they’ve actually attempted suicide or not. This can happen when a person doesn’t want to go to the hospital but expresses serious suicidal thoughts or intent to attempt. In these cases, someone can be legally held in a psychiatric hospital for 72 hours against their will.

In either scenario, if you need to be transported to a hospital, in many cases, the police are called.

Mighty contributor Jennifer Davis described what it was like being handcuffed after telling her therapist she was contemplating suicide. “My heart sank,” she wrote of her experience. “The officer took me to the side and told me to put my hands behind my back… Not once did anyone say I was going to be taken away like a criminal. I was devastated and embarrassed.”

Then, when someone is taken to their local psychiatric hospitals, conditions again vary. State hospitals tend to be different than private, more expensive institutions. In the two-year period before he died, Gary was admitted multiple times to a local, well-known psychiatric hospital.

Some stays came as a result of Gary telling Collingwood he didn’t feel safe or was afraid he might kill himself. Other stays, like the last time Gary was hospitalized (before Collingwood started asking those three questions every Sunday night), Collingwood discovered Gary had a suicide plan.

Although every admission was technically voluntary, there were times Collingwood said he would force his husband to go. “The only reason I’m going to the hospital is for you, so that you can sleep for a while,” Gary would tell him.

For people like Gary, with insurance and access to care, hospitalization during a suicidal crisis can catalyze mental health treatment, whether this looks like an extended inpatient stay or getting discharged to an outpatient program. For example, after his last hospitalization, Gary underwent electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) until a complication forced him to stop.

For others, hospitalization is a pitstop. According to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, as many as 70 percent of people who attempt suicide never attend their first appointment or maintain treatment after getting discharged from a hospital.

Not everyone who opens up to a mental health professional about suicidal thoughts is automatically hospitalized. Also, some people who lived through a suicidal crisis are thankful for their hospitalization. If they’re given a diagnosis (and find it helpful), it might provide some answers. Many meet fellow patients who make them feel less alone for the first time. Ideally, people leave the hospital with more knowledge and coping skills than when they came in.

In our Mighty survey, though, only 58 percent of people who were hospitalized after a suicide attempt reported they left the hospital in a better mental state than when they entered. The other 42 percent said they didn’t. One meta-analysis of suicide rates among psychiatric inpatients called the results “disturbingly high.“

“Suicide is about isolation. It’s about feeling like you’re a burden. And those things, I think, are basic human emotions that anyone could understand.”

“What we consider safety, what most people consider safety, which is calling the police, getting an ambulance, taking people to a hospital, is not in many cases safe to us,” said Dese’Rae L. Stage, a suicide attempt survivor and founder of Live Through This. She continued:

It makes us feel even more isolated, it makes us more scared. We lose our autonomy. Our comfort objects are taken from us. That would be my phone, or that would be music. Or for one of my family members who was hospitalized for saying he was suicidal, it was his shoes. They took his shoes, and he doesn’t like to be barefoot. Why would you the thing that people need to feel safe away from them in order to make them safe?

Alyse Ruriani, who also survived a suicide attempt, said she personally thought her own hospitalizations were necessary. For her, the hospital was a place to stabilize, a place to be safe when all she wanted to do was die.

“That isn’t to say they were great and there were no problems — there were plenty. It isn’t to say I was suddenly OK once hospitalized. I wasn’t,” she said. “But it is what I needed at the time.”

The problem, Ruriani explained, is that only after the fact do we know whose hospitalization made them “worse” and whose made them “better.”

We need to stop treating every suicidal person as if they are the same and as if the treatment should be the same. What works for one person won’t work for another. And one of the biggest things is the inconsistency among hospitals and inpatient programs. Some hospitals have awesome programs, some are neglectful or abusive. The fact that you never know what you will get is a problem, and that is something that keeps a lot of people from getting help and instead being afraid.

For people like Stohlmann-Rainey, who now uses her lived experience to advocate for suicide prevention, the fact that hospitalization is typically the only option for people who open up about being suicidal, and the fact that mental health professionals are expected to decide whether or not someone is at risk, is reflective of the fundamentally problematic way the mental health system treats people who are suicidal.

When it comes to suicide risk, instead of engaging with the part of people that want to live, she said, the system is set up to figure out who wants to die.

And keeping someone alive isn’t the same thing as giving them a reason to live.

“When people are hopeful, they’re not suicidal, but the system makes you feel really hopeless. The cultural attitudes about suicide make you feel hopeless,” Stohlmann-Rainey said. “So basically every message you get when you’re in that place is a message about hopelessness instead of something else. There’s a lot of things connected to that.”

The Trouble With Figuring Out Who’s at Risk

The way mental health professions try to predict who will kill themselves hasn’t improved in 50 years.

There are theories about why people kill themselves and when they’ll try. However, a meta-analysis that looked at half a century’s worth of research on suicide risk factors found none of these theories can completely explain suicidal thoughts and behaviors. “It is therefore likely that some of these theories are largely inaccurate, others are partially accurate, and still others may only apply to specific populations or situations,” the authors wrote.

Although most major health and suicide prevention organizations list what they consider suicide risk factors and warning signs, because such a large population of people possess at least one of these factors at any given time, it’s difficult for professionals to accurately narrow down who’s at risk, according to the study.

There are some things we do know. For example, the suicide rate is highest in middle age, with white males accounting for 7 of 10 suicides in 2016. Risk factors include living with a chronic illness, experiencing childhood abuse, impulsive tendencies and depression.

Young people in the LGBTQA+ community are five times as likely to have attempted suicide compared to their heterosexual peers, and 40 percent of transgender adults report having made a suicide attempt. Although white folks have the highest suicide rate in the U.S., Native Americans are a close second — and suicide among black children ages 5 to 12 is almost two times higher than the rate among white kids of the same age range.

Feeling like a burden increases someone’s likelihood of dying by suicide. Having access to means — meaning something that can kill you, like a gun — also increases someone’s risk.

When it comes to the combination of factors that ultimately influence someone’s desire to die, though — and then what motivates them to actually go through with it — that’s something that hasn’t been measured in a way that has predictive power.

This matters because when health professionals need to make calls about who’s “at risk” for suicide and who’s not — who’s allowed to walk out their doors and go home after a session, and who’s in need of immediate intervention — they’re often shooting in the dark.

Also, people lie. During a presentation at the American Association of Suicidology’s 2018 conference, Matthew K. Nock, a suicide researcher at Harvard University, said that while two-thirds of people who died by suicide told someone ahead of time, an even higher percentage of people who died by suicide explicitly denied they were suicidal in their last communication before dying.

Sixty-four percent of people who attempt suicide visit a doctor in the month before their attempt and 38 percent in the week before. But, in the United States, only 10 states require suicide prevention training for healthcare professionals. Among those states, Reuters reported, “the duration and frequency of training required under state policies varies widely.” Some might need to complete one or two hours of training upon license renewal. Some might need to undergo six hours of training every six years.

Even if a healthcare professional is trained in suicide prevention, the focus tends to be on risk-assessment, not overall suicide prevention. Although there is no evidence and no research that shows hospitalizing people when they’re suicidal improves their long-term survival rate, when professionals are given unreliable risk assessments and vulnerable people, they’re left in a difficult position.

They either neglect to hospitalize someone who seems at risk and the person goes on to kill themselves. Or, they hospitalize them. Maybe the experience keeps the person safe and helps them get the support they need. Maybe it’s unnecessary, or worse, traumatizing, and turns them off from getting help in the future.

Maybe they die anyway, since recently discharged psychiatric patients have one of the highest suicide rates of any identified risk group.

Bart Andrews, Ph.D., argues the way the mental health system is set up, health care providers are incentivized to use extreme measures when someone reveals they’re suicidal — even if this means unnecessarily hospitalization.

A suicide attempt survivor himself, Dr. Andrews is the Vice President of Telehealth and Home/Community Services at Behavioral Health Response, which offers confidential telephone counseling, as well as mobile outreach services to people in mental health crises. He’s dedicated nearly 20 years of this life to suicide and crisis intervention.

When you talk to him about how harmful crisis intervention can be — and how ineffective risk-assessment is — he gets frustrated. Yes, some cases of hospitalization hurt more than help. Yes, autonomy is important, and people shouldn’t lose their rights just because they express suicidality.

“But the person who died by suicide is not the one holding the clinician or the facility to account,” he said. “The dead person is not the one suing the clinician.”

In Andrews’ experience, people who are suicidal aren’t hospitalized because it’s always the best choice. They’re hospitalized because both legally and emotionally, it’s less risky for clinicians to send someone to the hospital.

“A clinician can see 100 people with the exact same risk profile, and only one of them will kill themselves. But — but, if that one kills themselves, you’re going to feel freaking horrible, and you’re exposing yourself to legal liability,” Andrews said.

Lawsuits after a suicide account for the largest number of malpractice suits against psychiatrists. According to a piece in the journal, “Innovation in Clinical Neuroscience,” examples of allegations in these lawsuits include failure to properly evaluate and record patient’s risk for suicide, failure to hospitalize for suicidality, failure to document an adequate suicide assessment and failure to take reasonable steps to ensure the patient’s safety.

When sued, most of the time clinicians win cases. But the risk is still real. Time, money and their license are on the line.

The emotional toll is also real. A 2013 study found mental health professionals who lose patients to suicide grieve similarly to those who have lost a family member. This loss hurts them personally but sometimes changes them professionally, too. The study found “greater conservatism in the handling of patients and record-keeping, hospitalization of low-risk outpatients, and refusal to accept referrals of any patients known to have suicidal tendencies” were all ways professionals may be affected after losing a patient to suicide.

The frequency of a mental health professional losing a patient to suicide ranges from 22 to 51 percent.

“Calling the police on someone at risk for suicide happens probably hundreds of times across the throughout our country. We have no idea that they save more lives… Some people are found and hospitalized and they live… It’s the other things we don’t know about. What’s the indirect consequence of that?”

Without adequate tools — and with the threat of a lawsuit dangling over their heads — it makes sense mandated reporters like clinicians are quick to hospitalize people expressing suicidal intent.

“This is the actual legal environment that clinicians and facilities work in, live in, breathe in,” Andrews said, adding:

You have broad protection for being aggressive and hospitalizing, physically restraining people, taking away their shoelaces, all that kind of stuff. Because if you don’t take someone’s shoelaces away and they hang themselves with shoelaces, you’re going to get sued, and you’re going to feel bad.

Andrews emphasized that generally, there are better outcomes for people who seek support than for those who do not seek support at all.

“It has saved some people’s lives. I think it saves people’s lives every single day,” Andrews said. “What we don’t know is how many people we lose because we use these procedures. I don’t know what that number is. I couldn’t tell you.”

Until mental health professionals are both better trained and less afraid of the emotional and legal toll of losing someone to suicide, Andrews argues, the part of the system many with lived experience don’t like — the part that stripped away their autonomy and locked them in a hospital to keep them “safe” — won’t change. Suicide crisis management will continue to operate as an emotional and legal liability machine, fear-based and essentially designed to protect itself. Andrews said:

I believe it hurts, I believe it does. If people knew they weren’t going to instantly be hospitalized, or that it would be very difficult to hospitalize them just because they’re talking about suicide, I think a hell of a lot more people would come forward.

A Different Kind of Help

When Andrews refers to training — the ones he thinks every clinician should be required to have, he’s not just talking about basic risk-assessment. He’s talking about approaches that tackle suicide more holistically.

Because while clinical interventions like medication and therapy can be vital in helping people struggling with, for example, depression, treating mental illness is not always synonymous with preventing suicide. According to The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than half of those who died by suicide did not have a known mental health condition.

Despite this, Andrews said, there are no specific funding streams or treatment codes for suicide prevention. Rather, we treat it like a secondary “side effect” to a primary mental health diagnosis. As a result, many mental health professionals diagnose mental illness as the primary contributor to suicide and exclusively work on treating that without considering other factors.

While there is a lot we don’t know about preventing suicide, there are some things we do know, he argues. We’re just not doing a great job implementing them.

He points to programs like Zero Suicide as a possible solution.

Zero Suicide is a framework that aims to make suicide prevention in the mental health system less fragmented and more comprehensive. It offers training and consultation for professionals and health care centers, with the goal of preparing professionals to talk to patients about suicide while also empowering them to actually help during a crisis instead of automatically sending patients along to more intensive care.

In a video on the Zero Suicide website, Mike Hogan, co-lead of the Zero Suicide Advisory Group, describes the problem Zero Suicide is trying to solve like this:

We don’t ask [about suicide], we don’t want to ask. We don’t want to talk about it… And when we ask, what do we do? Send someone to the hospital, as if that’s going to solve the problem? Or, do we roll up our sleeves and help them with their life, help them keep themselves safe?

This approach includes empowering mental health professionals to talk to their patients about suicide; working with patients to make safety plans that can then be communicated to trusted friends and family; supporting people as they deal with the issues and challenges in their lives, not just attempting to “fix” depression or mental illness; and following up to see how someone’s doing, even after a suicidal crisis has passed.

It’s more complicated than hospitalizing everyone who seems suicidal, and it means taking a more individualized approach to care. But there’s proof it can work. According to Zero Suicide, one health care organization found a 75 percent reduction in the suicide rate after implementing these methods. Another saw a reduction in suicide deaths from 35 per 100,000 patients to 13 per 100,000 patients after implementing Zero Suicide for three years.

Trainings that empower mental health professionals to support people who are suicidal, instead of reacting out of fear, have the potential to help people through suicidal crises in a meaningful and more sustainable way, meaning clinicians can focus on what each individual needs, rather than trying to guess who is going to take their lives and resorting to the most restrictive response.

There are also organizations that have been harnessing the power of peers — embracing the fact that some who are suicidal may not need mental health treatment but rather, someone to simply help them get through it. Stohlmann-Rainey works at a peer support line, and through her local crisis center, callers can choose to talk to either a counselor or a peer.

When people call Stohlmann-Rainey, her job isn’t to find out how “at risk” the caller is — her job is to talk to them. Because talking to a peer means talking to someone who’s been through it, she finds people are more willing to be real with her.

Similarly, peer-run respite centers can also play a role in suicide prevention, giving people a space to go when they’re struggling with suicidal thoughts. According to Zero Suicide, respite care has shown to have better outcomes than acute psychiatric hospitalization.

Whether a person struggling with suicidal thoughts needs treatment for depression, trauma-informed care or a more supportive environment, nothing happens in a vacuum. Mental health treatment can be part of that solution, but it can’t be the only thing we turn to when people are in need. When people do turn to the mental health system for help during a crisis, they need more options. They need a more tangible form of hope.

A week before Gary died, New York Times Magazine published an article that mentioned a ketamine trial happening at Massachusetts General Hospital, not far from where Collingwood and Gary lived. Collingwood said he read this story to Gary, that ketamine was supposedly a promising new treatment for depression, and immediately called Mass General to see if Gary would qualify for the study.

After returning to his office 10 days after Gary died, Collingwood had a message on his answering machine from the hospital. They wanted to get more information about Gary to see if he could be enrolled in the study.

Now when Collingwood sees results for ketamine trials, and how it has been found to help some people, he gets hopeful that progress is being made, but he can’t help getting a little mad at Gary. “There may have been a treatment that could have worked,” he said. “He didn’t stay long enough to find out.”

Making Hope Tangible

“Treatment-resistant depression” is one of the worst phrases ever invented, according to Collingwood. He says this because he’s a communications professional (“As a public relations person, the branding sucks.”) and also because he remembers the look on Gary’s face when doctors told him this was what he had.

“I remember Gary hearing that phrase and saying, ‘That sucks,’” Collingwood said. “He thought, ‘Well, of course, I have treatment-resistant depression because I’m a loser. Of course, I would have that kind of depression.’”

Whenever a treatment didn’t work for him, Gary believed it was his fault. And while Collingwood is thankful for all doctors did for Gary, sometimes how treatment was communicated would end up making Gary feel more hopeless. Every time something didn’t “work” — from medications to cognitive behavioral therapy — Gary took it as a personal failure. When Gary had to stop ECT, Collingwood described this as “the last straw.”

“That’s where he lost his hope. For Gary, there was a great sense of blame. His view was, ‘I can’t even fucking do ECT right.’” Collingwood said. “It really becomes a vicious cycle that’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Stohlmann-Rainey has a friend who will duct-tape his knives together when he’s feeling suicidal. He leaves them in his kitchen, while Stohlmann-Rainey and a few others sit with him in the living room. He doesn’t like to sleep while other people are there, so when he says he’s ready, they leave, trusting his duct-taped knives will keep him safe.

“If you take away someone’s power, you don’t know that you’re getting them through. You’re not getting them through anything, you’re just owning it,” Stohlmann-Rainey said. “It is not our job to prevent every suicide. It is our job in suicide prevention to get people better options.”

The idea of giving people who are suicidal more power, more “freedom,” when they’re in a dangerous moment is scary. As humans, we desperately want to save each other. We want to know we’re doing everything we can to keep each other safe. “I could have handcuffed myself to Gary,” Collingwood said, talking about the guilt he had to move through after his husband’s death. “I just think he couldn’t stay here any longer.”

If our country finally begins to treat suicide like the public health issue it is — and if suicide prevention campaigns are going to keep telling people to get help, to reach out — there needs to be more tangible hope on the other side.

This will take money for research, services and training.

This will take mental health providers feeling prepared, confident and brave enough to help people get through suicidal crises in a meaningful way.

This will take facing the fact that the stigma of mental illness isn’t always to blame and that fighting for a more equitable world — whether someone is facing the aftermath of trauma, racism, poverty, homophobia — needs to be just as part of the solution as getting people in mental health treatment.

This will take connecting people with others who get it, so at the very least, no one’s going through this alone.

This will take creativity — working with people with lived experience to create more nuanced responses to suicide, instead of throwing everyone in the same bucket because we’re scared.

This will take giving people tools to live the lives they want to live and instead of just temporary keeping people safe when they’re in danger, focusing on solutions that give them a reason to stay.

This is all hard to talk about. We don’t want to dissuade people from getting help. But unless we’re willing to try something different, it doesn’t matter how much suicide awareness we spread. Until we decide that treating people who are suicidal compassionately and effectively is a national priority, no matter how many times we share the suicide lifeline, we’re not going to get the change we look for.

There’s hope here.

There’s hope in suicide prevention awareness. There’s hope in the hashtags that spread. There’s hope in people with lived experience telling their stories, letting others know they’re not alone. There’s hope that this hope will find its way into classrooms and emergency rooms and hospitals, too.

Every time someone who’s suicidal pauses and reaches out, giving themselves one more chance, there’s hope. The system that’s supposed to there for us just needs to catch up.