What is Parkinson's Disease: Everything You Need to Know

Editor's Note

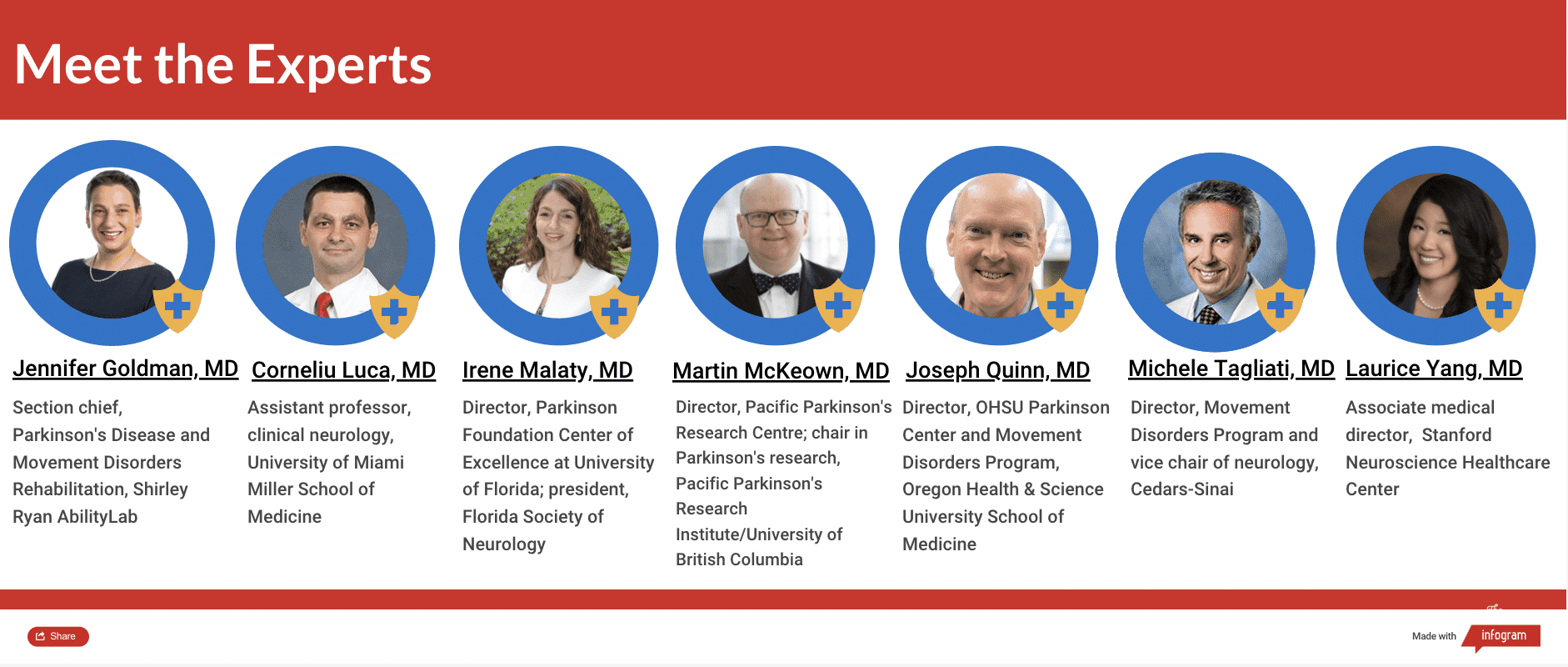

The Mighty’s Condition Guides combine the expertise of both the medical and patient community to help you and your loved ones on your health journeys. For this guide, we interviewed seven medical experts, three patients, read numerous studies and surveyed nearly 400 people living with Parkinson’s. The guides are living documents and will be updated with new information as it becomes available.

Other sections of this Condition Guide:

Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Resources

What you’ll find in this section:

What Is Parkinson’s Disease? | What Causes Parkinson’s Disease? | Who Gets Parkinson’s Disease? | Why Do People Get Parkinson’s Disease? | Is Parkinson’s Disease Hereditary? | Celebrities With Parkinson’s Disease | Long-Term Outlook of Parkinson’s Disease | Parkinson’s Disease Statistics

This section was medically reviewed by Kristin Andruska, MD, PhD, Head of the California Movement Disorders Center

What Is Parkinson’s Disease?

You might be wondering, “What is Parkinson’s disease?” It’s more than just a medical definition. Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that affects your body’s ability to produce dopamine, a chemical found in your brain that helps you initiate and control your movements. Signs of Parkinson’s disease include uncontrollable shaking in your limbs (known as a tremor), slow movement, a rigid, stiff feeling in your body, unsteady gait and posture, as well as symptoms unrelated to movement like loss of smell, constipation, difficulty sleeping, fatigue, cognitive challenges and blood pressure issues. Parkinson’s most frequently develops in people over age 50, but can also appear in younger individuals, too.

What is Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease symptoms can make you feel stiff, like it’s hard to move your muscles, and maybe you have uncontrollable shaking in one or more of your limbs or fingers. You might also feel fatigued and have difficulty feeling motivated to get up. Everyday tasks like brushing your teeth, putting on your clothes, cooking and driving a car might be a struggle due to the stiffness and slowness of your muscles. Perhaps family members have noticed you don’t swing one of your arms when you walk.

Feeling unsteady when you walk and feeling like you can’t move as quickly as you want could be everyday occurrences along with other challenges like constipation, chronic pain, difficulty sleeping and concentrating, a weak sense of smell, having a soft voice and a bent-over posture. Taking certain medications helps wake your muscles up and gets you moving with more ease and less sluggishness. Without that help, though (and, sometimes, despite taking medications), moving the way you used to is challenging, as you constantly feel a sense of slowness, stiffness and/or shaking (you might experience some or all of these symptoms). If this describes your experience, you may be living with Parkinson’s disease.

There are several different types of Parkinson’s disease, including:

Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: This is the most common type and refers to cases where the cause of the disease is unknown.

Parkinsonism: This is used to describe a group of disorders that affect a person in similar ways to Parkinson’s disease but are caused by other factors, such as certain medications, brain injury, or other underlying conditions.

Parkinson’s-plus syndromes: These are a group of neurodegenerative disorders that share some symptoms with Parkinson’s disease but also have additional aspects to them.

Drug-induced Parkinsonism: Some medications, such as certain antipsychotics or anti-nausea drugs, can cause symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease.

When people think of Parkinson’s disease, the first (and often only) thing that comes to mind is its most well-known symptom: a tremor in your hand. But as anyone who has Parkinson’s disease knows, there’s so much more to the condition than that. This is a condition that can cause both invisible and visible symptoms, physical and emotional impacts. It affects each person in a unique way. Two people can have two completely different experiences — and both are completely valid.

What Causes Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease occurs when there isn’t enough dopamine produced in the part of the brain called the substantia nigra, which helps you initiate muscle movement. The substantia nigra part of your midbrain normally produces dopamine, a chemical called a neurotransmitter that signals other brain cells to start movement. But in Parkinson’s disease, the brain cells (aka neurons) that produce dopamine degenerate and die, meaning less and less dopamine is produced. Without dopamine in the substantia nigra, you have a harder time initiating and controlling your movements.

Another key feature of Parkinson’s disease is when a protein found in the brain called alpha-synuclein (abbreviated a-synuclein) clumps together with other proteins to form Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies are toxic, and can form in many areas of the brain, including the substantia nigra and cerebral cortex (the “thinking” part of the brain). Lewy bodies disrupt the functioning of these areas of the brain — neurons can’t work properly and send the signals they are supposed to. The neurons eventually die, making it impossible for them to carry out their intended functions.25

As a result, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by three hallmark movement, or motor, symptoms:

- Tremor, or uncontrolled shaking of typically a hand, leg, foot, head, chin, lips, jaw or tongue while the limb is at rest

- Bradykinesia, or slowness of movement

- Rigidity, or stiffness in the body

Other early signs of Parkinson’s disease include an unsteady gait, balance problems, soft voice, small handwriting, stooped posture, “freezing” of feet and lower limbs while walking, and taking very small steps.

Parkinson’s disease also causes symptoms unrelated to movement. Dopamine-producing neurons are found in parts of the brain besides the substantia nigra, such as areas that control your mood and sense of motivation to do things. Lewy bodies can also be found in parts of the brain that affect things like your sense of smell, thinking, constipation, sleep, and depression, which causes symptoms in these areas, too.

Non-motor symptoms can be just as challenging to live with as motor symptoms, sometimes more. These symptoms often show up months or even years before the motor symptoms, suggesting perhaps the disease can begin in parts of the brain outside the dopamine-producing neurons of the substantia nigra, cause non-motor symptoms, and gradually progress to include the motor symptoms as well.28

Some of the non-motor symptoms you experience can include:

- Loss of smell

- Constipation

- Sexual dysfunction

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Apathy, or the lack of desire to move or do things

- Sleep problems

- Cognitive problems

- Fatigue

- Sweating

- Autonomic dysfunction, or trouble with automatic body functions like blood pressure fluctuations, dizziness or feeling faint

Parkinson’s disease is degenerative, which means over time, symptoms get worse. There is no cure. However, it is not considered a terminal illness. For those living with Parkinson’s disease, life expectancy varies from person to person, but despite its degenerative nature, there are a number of treatments that can help you manage your symptoms, including:

- Medication

- Exercise

- Physical, occupational and speech therapy

- Surgery

The role of therapies cannot be overstated in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Physical therapy can assist with movement and balance problems, helping to maintain independence and safety. Professional therapy provides strategies to manage daily activities, adapting tools and environments to accommodate the changing physical abilities of the person with Parkinson’s disease. Speech therapy, on the other hand, addresses difficulties in speech and swallowing often associated with the disease.

In the face of Parkinson’s disease, a holistic and proactive approach to healthcare is fundamental. Through medication, exercise, and a range of therapies, those living with Parkinson’s can equip themselves with the necessary tools to manage their symptoms and live a fuller, more active life. The key lies in early detection, regular monitoring, and a comprehensive management plan.

Parkinson’s disease is named after James Parkinson, an English scientist who wrote the first paper describing its symptoms. His paper, “An Essay on the Shaking Palsy,” was published in 1817.24

Who Gets Parkinson’s Disease?

An estimated 6.1 million people worldwide had Parkinson’s disease in 2016, up from 2.5 million people in 1990. Between 2005 to 2030, the number of people with Parkinson’s disease is expected to double.9 This is because people, in general, are living longer, and Parkinson’s becomes more common as you get older.

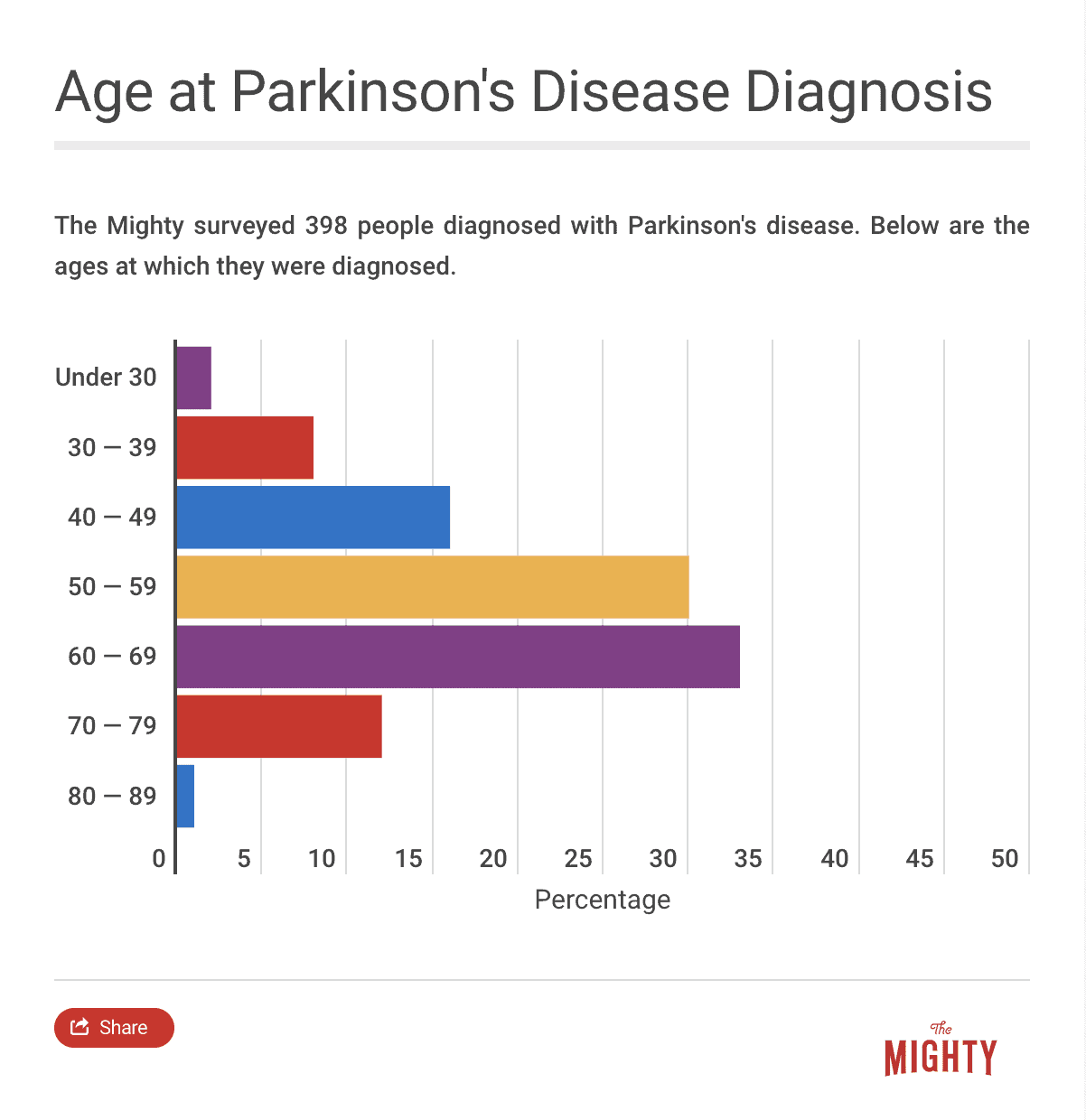

Age of Onset

Age is the biggest risk factor for Parkinson’s disease. It affects about 1% of the population over age 60, and 5% over age 85.26 Your risk of developing Parkinson’s increases with each decade. However, anywhere from 5-20% (research is inconsistent) of cases are considered early-onset, which is defined as presenting with symptoms before age 50.36

We don’t know for sure why Parkinson’s becomes more common with age but research suggests some people experience a decline over time in the processes required for the functioning of the substantia nigra. As some people age, they may progress through the stages of Parkinson’s disease, where they become less able to produce dopamine, neurons become less effective and toxic Lewy bodies develop that cause neurons to die. When all these factors combine, some people experience the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.26

Gender Differences

Parkinson’s is more common in men than women, with a ratio of about 1.5 men to every 1 woman. The ratio appears to increase with age.17 Why more men are diagnosed with Parkinson’s than women is not completely clear. There may be a relationship between dopamine and estrogen, the female sex hormone. Some research suggests estrogen might help protect against the loss of dopamine, which could explain why women are less likely to have Parkinson’s and also why Parkinson’s symptoms are sometimes worse for women after menopause, when estrogen levels decrease.32 There is also evidence that women with Parkinson’s are less likely than men to seek out a specialist for care, which means they may be underrepresented in research and not receive the same quality of care.35

Another theory is that male-dominated industries are associated with environmental factors that may increase Parkinson’s risk — for example, being exposed to pesticides and heavy metals (such as manganese exposure from welding, iron, steel and mining2). It also could be that women are simply not diagnosed with Parkinson’s as readily as men are. Women may experience more non-motor symptoms, which can be harder to diagnose as Parkinson’s than motor symptoms because they still aren’t as recognized.10

Related: These stories share women’s perspectives on living with Parkinson’s.

- Is There Anything Good About Living With Parkinson’s? These Women Say Yes!

- Choosing Parenthood With Juvenile Parkinson’s Disease

Why Do People Get Parkinson’s Disease?

The first thing you might ask after getting the diagnosis is why did I get Parkinson’s disease? Scientists don’t know for sure what causes some people to develop Parkinson’s while others don’t. If you ask your doctor why you have Parkinson’s, they will likely not be able to give you a definitive answer. But scientists have pinpointed a couple of factors that may increase your risk of Parkinson’s: genetics and environmental factors.

Is Parkinson’s Disease Hereditary?

Historically, Parkinson’s was not thought of as a hereditary or genetic condition. Newer research, however, indicates Parkinson’s disease can run in families, though it is rare. These cases are called familial Parkinson’s disease and account for about 15% of all Parkinson’s cases.23 Scientists have identified several genes that can cause or increase your risk of Parkinson’s. It’s possible for mutations or changes in these genes to be passed down among family members. In very rare cases, they can appear at random, causing Parkinson’s disease in someone who did not inherit the gene from a family member and has no family history of the condition.

Genetic Factors

Researchers have identified several genes that increase your risk of developing Parkinson’s. Experts believe a gene called LRRK2 is linked to Parkinson’s because studies have found several types of mutations in LRRK2 that people with Parkinson’s disease have in common. It may explain at least 5% of familial Parkinson’s disease cases and 1-2% of “sporadic,” or non-familial, Parkinson’s cases.27 The LRRK2 gene makes a protein called LRRK2 (also called dardarin), found in the brain, which is believed to be involved in several functions, including regulating other proteins’ abilities to interact with each other, transmit signals and build the framework of other cells. We don’t know exactly why LRRK2 mutations lead to Parkinson’s symptoms specifically, but we know that mutations to LRRK2 result in the protein being hyperactive, which disrupts how effectively it can work and can cause brain cells to die.27

One particular type of LRRK2 mutation, called G2019S, appears to be particularly concentrated in certain ethnic groups. It accounts for:

- 13.3% of sporadic and 29.7% of familial Parkinson’s disease among Ashkenazi Jews

- 40.8% of sporadic and 37% of familial Parkinson’s disease among North African Arabs12

A gene called GBA is also associated with Parkinson’s — an estimated 10% of people with Parkinson’s have a GBA mutation.13 The GBA gene makes an enzyme — a type of protein that helps brain chemicals communicate more efficiently — that breaks down toxic substances in neurons, digests bacteria and breaks down worn-out cells. Scientists don’t know the exact connection to Parkinson’s, but in theory, if there is a mutation on GBA, toxic substances in neurons may not be able to break down, which could kill dopamine-producing neurons.8

Another gene, called PRKN, is associated with developing early-onset Parkinson’s in particular. The PRKN gene is responsible for the production of the parkin protein, which is believed to help get rid of damaged cell parts, like mitochondria — the part of the cell that produces energy.22 PRKN gene changes may allow a buildup of toxic proteins and damaged mitochondria, which causes the death of dopamine-producing cells.31

Also, damaged mitochondria in dopamine-producing cells could prevent them from working properly since they can’t produce energy.21 Some studies have found that PRKN mutations are found in 40-50% of early-onset familial Parkinson’s cases and 1-20% of sporadic Parkinson’s cases.20 Hispanic individuals are more likely than non-Hispanic individuals to carry this gene.1

Mutations in the SNCA gene are also believed to increase your risk of developing Parkinson’s disease since SNCA produces a-synuclein, the protein that builds up in people with Parkinson’s.20 A-synuclein clumps are also called Lewy bodies, and the presence of Lewy bodies in the brain is a hallmark sign of Parkinson’s disease. Lewy bodies in the brain can disrupt the functioning of neurons, leading to Parkinson’s symptoms.

Environmental Factors

There is some evidence that certain external factors could increase your risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. One of these factors is exposure to pesticides. One study found people exposed to pesticides rotenone and paraquat were 2.5 times more likely to develop Parkinson’s.33

Rotenone is a chemical used mostly by organic farmers to kill insects (it’s considered organic because it is found naturally in some plants), and it is also used in some household insecticide products; for example, products with the brand name Bonide. It’s also used by fishermen to kill non-native fish species.29 Paraquat is used as a commercial herbicide, to kill weeds and grass. It can only be used by people who have a license to do so.3

Genetics may influence the impact pesticide exposure has on your Parkinson’s risk.11 For example, if you have a gene that does not produce the enzyme supposed to protect against the toxic effects of the pesticide paraquat, your body will be more sensitive to paraquat exposure, leading to a higher risk of Parkinson’s disease.11 Pesticides may also explain why Parkinson’s is more common among men since pesticides are used more often in male-dominated farming industries.10

Another potential environmental factor is smoking. Studies show smokers have a lower incidence of Parkinson’s than non-smokers, possibly because nicotine protects dopamine neurons.19 Unfortunately, this may not be a useful protective factor, since smoking can lead to serious health problems like cancer and heart disease. Caffeine may also have a protective effect against Parkinson’s disease.14

Head injuries may also increase your risk of Parkinson’s. Research suggests head trauma is associated with the formation of abnormal clumps of the protein a-synuclein, called Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies are toxic to brain cells and are found in the brains of people with Parkinson’s disease4 (however, they are also found in people with other neurodegenerative diseases and in people with normal brains). Other theories are that head trauma simply “uncovers” underlying Parkinson’s disease that would have surfaced anyway, or that trauma damages dopamine-producing brain cells.5 One recent study of military veterans found having a mild traumatic brain injury increased their risk of developing Parkinson’s by 56%.7

Celebrities With Parkinson’s Disease

When you’re living with Parkinson’s, it can be comforting to know of other people who are going through the same diagnosis you are. One group that may provide some solace includes famous people with Parkinson’s disease. Celebrities who have Parkinson’s are also often active in advocacy work, which may offer great opportunities for you and your loved ones to get involved. In addition, celebrities tend to increase awareness of Parkinson’s disease, helping the general public, who may know very little about it, learn what the condition is. A few notable people with Parkinson’s disease are:

Michael J. Fox

Actor Michael J. Fox, best known for his appearances in “Back to the Future,” “Family Ties,” “Spin City” and “The Good Wife,” was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1991 at age 29. He publicly announced his diagnosis in 1998, and soon after founded the Michael J. Fox Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to funding Parkinson’s research.16

Alan Alda

Alan Alda is an actor best known for his appearances in “M*A*S*H,” “The West Wing” and in movies like “The Aviator” and “Bridge of Spies.” In 2018 at age 82, Alda revealed he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease three-and-a-half years earlier, after he noticed he had begun to act out dreams, a common indicator of Parkinson’s disease.18

Muhammed Ali

Boxer Muhammed Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 1984 at age 42. He became an advocate for Parkinson’s research and even founded an annual Celebrity Fight Night to raise money, along with the Muhammed Ali Parkinson Center in Phoenix, Arizona.15 He died in 2016 at age 74 of sepsis, which is not typically linked with Parkinson’s but could have been exacerbated by his physical condition.34

Rev. Jesse Jackson

Civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson announced he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016 at age 76. At the time of his diagnosis, he said he and his family had begun noticing “changes” three years earlier, and said he intended to make lifestyle changes and dedicate himself to physical therapy.30 His father also had Parkinson’s disease.

Neil Diamond

Neil Diamond, best known for songs like “Sweet Caroline” and “America,” revealed his Parkinson’s diagnosis in 2018 at age 76. He stopped touring but says he hopes to continue performing. When he announced his diagnosis, he said he is feeling good, staying active and taking his medications. He said he is feeling “very positive” about it and wants to keep the music coming.6

Related: Discover more celebrities who live with Parkinson’s.

- 9 Celebrities Who’ve Been Diagnosed With Parkinson’s Disease

- BBC Correspondent Shares Diagnosis After Viewers Notice Symptoms During Broadcast

Long-Term Outlook of Parkinson’s Disease

The long-term outlook of Parkinson’s has improved since James Parkinson’s essay was published. From a medication standpoint, there are several drugs you can try, including one considered the gold standard since the 1960s. These drugs can improve your motor symptoms. Deep brain stimulation surgery is also an effective treatment option for motor symptoms.

Doctors are also becoming more aware of Parkinson’s non-motor symptoms and can work with you to find appropriate medications and treatments to manage these symptoms. Other types of treatments, most importantly exercise, can also help lessen your motor symptoms.

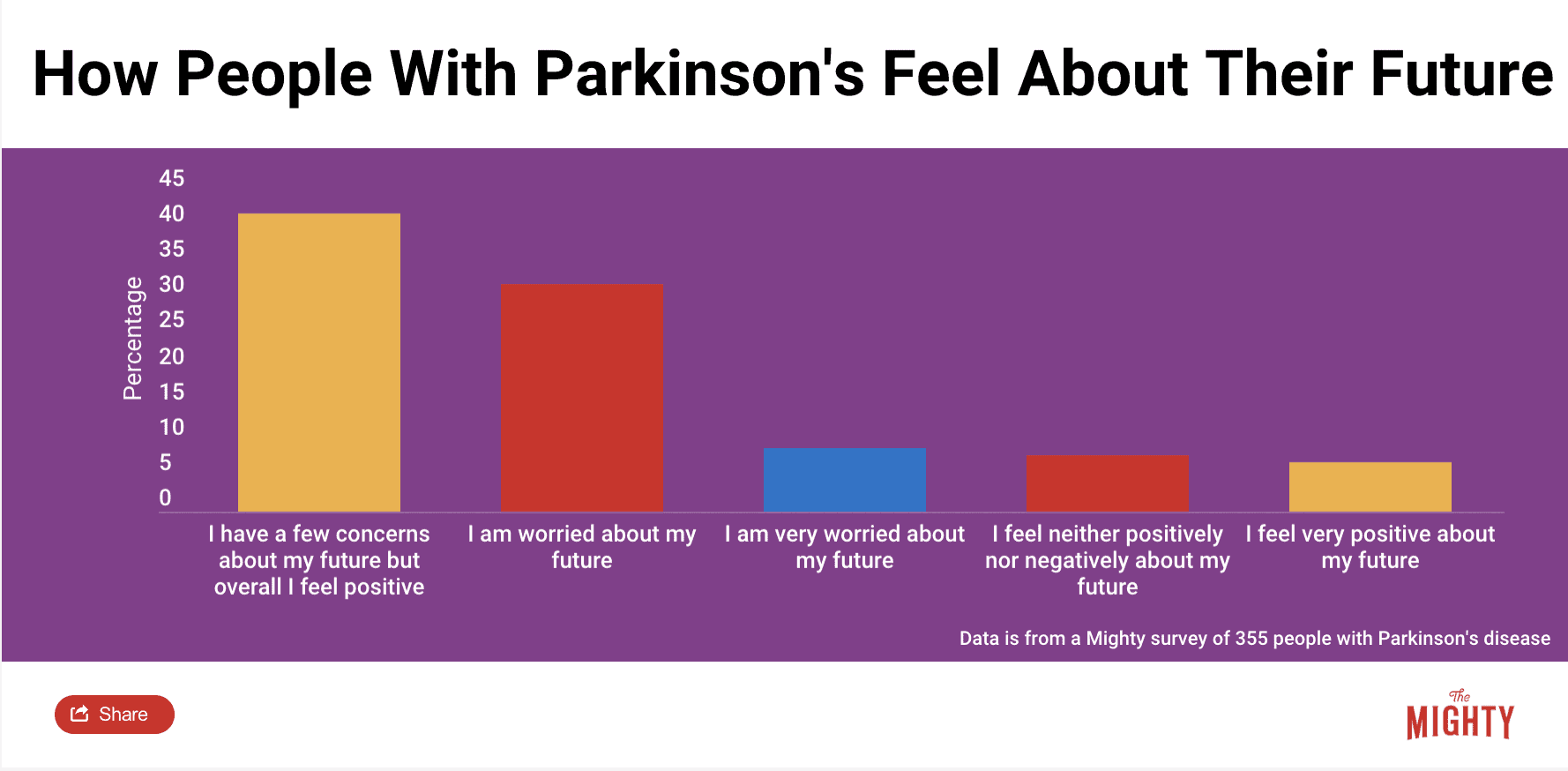

Parkinson’s disease is progressive, so symptoms get worse over time. However, the rate of progression varies significantly among people with Parkinson’s, so it’s difficult for any guide such as this one to predict how quickly you will progress and whether you will need mobility devices or caregivers. But the rate of progression for a single person tends to remain stable and predictable throughout your life, so your own doctor may be able to give you some insight.

Still, Parkinson’s is not considered a terminal illness. Rather, there are a few symptoms that can lead to life-threatening complications like pneumonia, loss of balance that can lead to serious falls, and Parkinson’s dementia. Rather than try to predict how quickly you will progress and worry about the future, it’s more productive to focus on managing your symptoms and lifestyle as well as you can right now. Incorporating Parkinson’s disease self-care practices into your daily routine and joining a Parkinson’s support group can help maintain a sense of control over your well-being.

Related: These stories share more about what it’s like living with Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s Disease Statistics

Check out these facts and figures for a quick look at the scope, causes and demographics of Parkinson’s disease.

- The average age at diagnosis is 60 years old.16

- About 6.1 million people worldwide are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.9

- About 1 million people in the United States have Parkinson’s disease.9

- 15% of Parkinson’s cases are caused by genetics.23

- The ratio of men with Parkinson’s to women with Parkinson’s is 1.5 to 1.

- An estimated 5-20% of Parkinson’s cases are considered early-onset, which is when symptoms present at age 50 or younger.23

Learn More About Parkinson’s Disease: Overview | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment | Resources

Sources

- Alcalay, R. N. et al. (2010). Frequency of Known Mutations in Early-Onset Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology, 67(9), 1116-1122. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2010.194

- Andruska, K. M., & Racette, B. A. (2015). Neuromythology of Manganism. Current Epidemiology Reports,(2), 143–148. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0040-x

- CDC | Facts about Paraquat. (n.d.). Retrieved June 28, 2019, from https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/paraquat/basics/facts.asp

- Crane, P. K., Gibbons, L. E., Dams-O’Connor, K., Trittschuh, E., Leverenz, J. B., Keene, C. D., . . . Larson, E. B. (2016). Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings. JAMA Neurology, 73(9), 1062-1069. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1948

- Dolhun, R. (n.d.). Ask the MD: Head Trauma and Parkinson’s Disease. Retrieved from https://www.michaeljfox.org/news/ask-md-head-trauma-and-parkinsons-disease?ask-the-md-head-trauma-and-parkinsons-disease=

- Fekadu, M. (2018, August 15). Diamond won’t let Parkinson’s slow him down, talks new DVD. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/432f4dec22a845f283675afec31f6bf9

- Gardner, R. C., Byers, A. L., Barnes, D. E., Li, Y., Boscardin, J., & Yaffe, K. (2018). Mild TBI and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology, 90(20). doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000005522

- GBA gene – Genetics Home Reference – NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/GBA

- GBD 2016 Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. (2018). Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurology, 939-953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30295-3

- Goldman, J. (2019, May 3). [Telephone interview].

- Goldman, S. M., Kamel, F., Ross, G. W., Bhudhikanok, G. S., Hoppin, J. A., Korell, M., . . . Tanner, C. M. (2012). Genetic modification of the association of paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 27(13), 1652-1658. doi:10.1002/mds.25216

- Kumari, U., & Tan, E. K. (2009). LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease: Genetic and clinical studies from patients. FEBS Journal, 276(22), 6455-6463. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07344.x

- Liu, G., Boot, B., Locascio, J. J., Jansen, I. E., Winder-Rhodes, S., Eberly, S., . . . Scherzer, C. R. (2016). Specifically neuropathic Gaucher’s mutations accelerate cognitive decline in Parkinson’s. Annals of Neurology, 80(5), 674-685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24781

- Liu, R., Guo, X., Park, Y., Huang, X., Sinha, R., Freedman, N. D., . . . Chen, H. (2012). Caffeine Intake, Smoking, and Risk of Parkinson Disease in Men and Women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 175(11), 1200-1207. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr451

- McCallum, K. (2016, June 10). Muhammad Ali’s Advocacy for Parkinson’s Disease Endures with Boxing Legacy. Retrieved from https://parkinsonsnewstoday.com/2016/06/10/muhammad-alis-advocacy-parkinsons-disease-endures-boxing-legacy/

- The Michael J. Fox Foundation. (n.d.). Retrieved June 14, 2019, from https://www.michaeljfox.org

- Moisan, F., Kab, S., Mohamed, F., Canonico, M., Guern, M. L., Quintin, C., . . . Elbaz, A. (2015). Parkinson disease male-to-female ratios increase with age: French nationwide study and meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 87(9), 952-957. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2015-312283

- Moniuszko, S. M. (2018, July 31). Alan Alda reveals he has Parkinson’s disease, was diagnosed more than 3 years ago. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/people/2018/07/31/alan-alda-reveals-he-has-parkinsons-disease/869856002/

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (n.d.). Parkinson’s Disease and Environmental Factors. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/materials/parkinsons_disease_and_environmental_factors_508.pdf

- Oczkowska, A., Kozubski, W., Lianeri, M., & Dorszewska, J. (2013). Mutations in PRKN and SNCA Genes Important for the Progress of Parkinson’s Disease. Current Genomics, 14(8), 502-517. doi:10.2174/1389202914666131210205839

- PRKN gene – Genetics Home Reference – NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved July 2, 2019, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/PRKN

- PARKIN; PARK2. (n.d.). Retrieved July 2, 2019, from https://www.omim.org/entry/602544

- Parkinson disease – Genetics Home Reference – NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved May 23, 2019, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/parkinson-disease

- Parkinson, J. (2002). An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. Journal of Neuropsychiatry, 14(2), 223-236. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.14.2.223 (Reprinted from Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1817, London)

- Poewe, W., Seppi, K., Tanner, C. M., Halliday, G. M., Brundin, P., Volkmann, J., . . . Lang, A. E. (2017). Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3(1). doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.14

- Reeve, A., Simcox, E., & Turnbull, D. (2014). Ageing and Parkinsons disease: Why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Research Reviews, 14, 19-30. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.01.004

- Refai, F. S., Ng, S. H., & Tan, E. (2015). EvaluatingLRRK2Genetic Variants with Unclear Pathogenicity. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1-6. doi:10.1155/2015/678701

- Rietdijk, C. D., Perez-Pardo, P., Garssen, J., Van Wezel, R. J., & Kraneveld, A. D. (2017). Exploring Braak’s Hypothesis of Parkinson’s Disease [Review]. Frontiers in Neurology. Retrieved July 3, 2019, from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2017.00037/full

- Robertson, D. R., & Smith-Vaniz, W. F. (2008). Rotenone: An Essential but Demonized Tool for Assessing Marine Fish Diversity. BioScience, 58(2), 165-170. doi:10.1641/b580211

- Scutti, S. (2017, November 17). Jesse Jackson diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/17/health/jesse-jackson-parkinsons-bn/index.html

- Shimura, H., Mizuno, Y., & Hattori, N. (2012). Parkin and Parkinson Disease. Clinical Chemistry, 58(8), 1260-1261. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2012.187054

- Shulman, L. M. (2002). Is there a connection between estrogen and Parkinsons disease? Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 8(5), 289-295. doi:10.1016/s1353-8020(02)00014-7

- Tanner, C., Kamel, F., Ross, G. W., Hoppin, J. A., Goldman, S. M., Korell, M., . . . Langston, J. W. (2011). Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson’s disease. Environmental Health Perspectives, 119(6), 866-872. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002839

- Tinker, B. (2016, June 09). What killed Muhammad Ali? Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2016/06/09/health/muhammad-ali-parkinsons-sepsis/index.html

- Willis, A. W., Schootman, M., Evanoff, B. A., Perlmutter, J. S., & Racette, B. A. (2011). Neurologist care in Parkinson disease: A utilization, outcomes, and survival study. Neurology, 77(9), 851–857. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e31822c9123

- Young-Onset Parkinson’s Disease. (n.d.). Retrieved June 27, 2019, from https://www.michaeljfox.org/news/young-onset-parkinsons-disease