Addressing My Mental Health as an Asian-American Amputee and Childhood Cancer Survivor

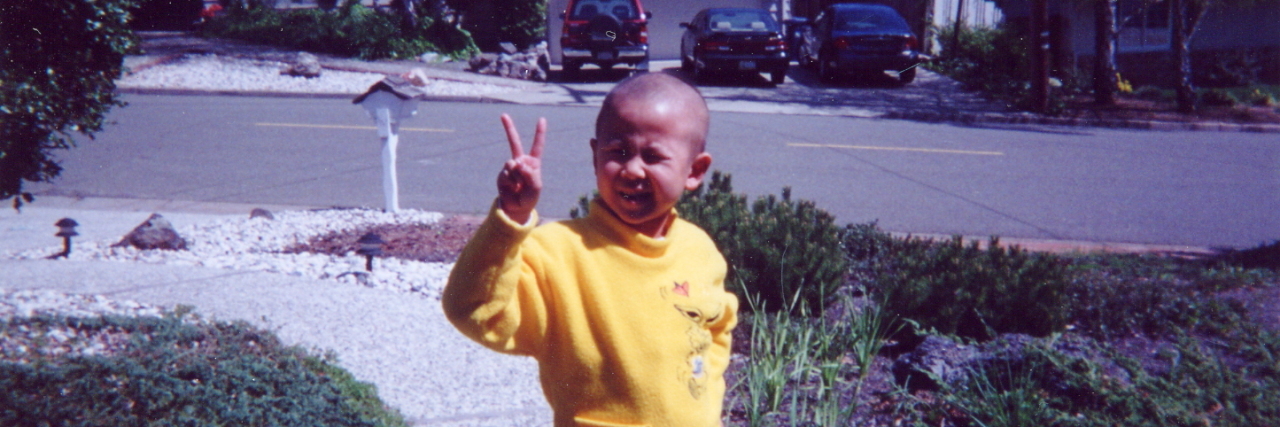

A few months ago, I hung up the phone and sighed in defeat for what felt like the hundredth time. Since the end of 2020, I have been on the search for a therapist for the first time in my life. At this point, I had repeated and memorized the summary of the past 26 years of my life: “I was diagnosed with osteosarcoma at the age of 5, and they later had to amputate my leg at the age of 6. I know I have struggled with anxiety, and I am pretty sure that my childhood history with cancer has caused me some form of PTSD. I would also like to work with someone who also has a cultural understanding of growing up as an Asian-American. So… do you think that we can work together?”

You might be wondering: why was I just starting to look for help? The answer is easy: I didn’t think I needed it. Growing up, I thought I was pretty lucky: I beat cancer, I only lost one leg (and am still pretty mobile with my prosthetic leg), and I am now in good physical health. I could feel my privilege of being alive and beating cancer when I saw so many friends and family like me go through cancer recurrence or even lose their battle against cancer.

As a childhood cancer survivor and amputee, I have always felt pretty self-conscious of my medical history and my visible disability. The conversations with strangers always go the same way:

“How did you lose your leg?”

“Cancer?! At that age? You poor thing!”

“I’m so sorry for your loss.”

While most people mean well, I have learned that there is a very clear difference between sympathy and empathy. Honestly, it just makes me laugh sometimes. “I’m sorry for your loss?” I mean, my residual left limb thanks you for expressing your deep compassion for its lost other half; otherwise, please save that for someone else. As you can probably tell, I tend to resort to humor or sarcasm as a coping mechanism. It’s funny and a bit sad when you think about it; whenever I feel uncomfortable about people staring at my leg or feeling sorry for me, I will make a joke or just internalize it to make sure that they were comfortable and didn’t feel awkward, disregarding how it may have made me feel.

I’ll be frank: I am 100% aware of when people are looking at me and my leg, and I am uncomfortable 100% of the time they are looking at me. I can see when adults pull their children away from me, thinking that it’s rude to ask (it’s not at all; I am happy to answer all of your kids’ questions so we can normalize disabilities in conversations). I cringe every time someone does a double-take at my leg. It’s been 20 years since I became an amputee, and it hasn’t gotten easier, but I’ve learned to do a pretty good job at hiding my reactions.

It took me a very long time to even realize that I was allowed to seek help. Mental health isn’t a common topic in Asian households. Our family certainly cared for each other’s health and wellbeing, but the topic of mental health and how we were feeling never really came up. After my diagnosis and amputation, “how are you feeling” meant “how are you doing physically?” If something was bothering me mentally, I didn’t know how to process it, because I didn’t even know what it was and what it meant. I eventually learned to shrug it off and internalize my feelings, as it felt like it wasn’t a big deal and I needed to be grateful for even having the option of feeling any sort of way.

When I was growing up, I learned that my name in Chinese roughly translated to “Sunshine.” I remember my parents telling me what it meant, and proudly saying how fitting it was, considering I was always so positive and upbeat despite everything that I had been through. I always had mixed feelings about my Chinese name growing up. I have had people make fun of the pronunciation when I would finally share it; I have had people make fun of my middle name when they saw it on official school documents (my middle name is actually the pronunciation of my Chinese “first name”). When I heard that my name meant something so positive and so warm, I found a new pride in it; however, with that pride, I took the translation almost too seriously. I was already a generally positive person and already wanted to ensure that my peers were not uncomfortable with my visible disability. Now, I felt some sort of obligation to live up to my given name and continue to spread positivity, even if I wasn’t feeling it.

There were a lot of external pressures outside of my family environment that made it difficult to seek help. The expectations and pre-established beliefs created by the Model Minority Myth made me feel as if I was held to a higher standard than my non-Asian peers. These dangerous stereotypes portray Asian-Americans as “model minorities” — highly intelligent in academic settings and successful in their careers. Growing up, academically, I didn’t fit the “model minority” stereotype; I was just average at all subjects. In addition, I didn’t even meet others’ standards physically; I was missing one leg and could barely participate in sports that required walking or running. Addressing my mental health issues on top of my misfit into societal standards just made me feel even more weak; Megan “Sunshine” Liang it is.

It has taken me practically 20 years to realize that it’s OK to not be OK, even despite how much you’ve braved and overcome. It took immersing myself into a community of amputees to learn that my experiences and feelings were valid and not unique to myself. It took reading stories from other Asian-Americans who also did not fit in the mold to realize that I didn’t have to fit any societal standards that others tried to put on me. Now, I always talk about the importance of community to the point that I sound like a broken record. Having a community can do wonders for validating not only the experiences that you may find unique to your disability, but the feelings you might have internalized or even vocalized about existing as a person with a disability. It felt even sweeter when I joined Asian-Americans with Disabilities Initiative, or AADI, this summer. Being a part of this community that understands your entire experience and feelings of having multiple marginalized identities is so important.

My search for the right therapist continues, but I oddly feel more at peace with myself than ever. It’s OK to not be OK, and it’s OK for you to take time to realize that. In the meantime, I’m going to work on finding a more authentic definition of “Sunshine” and try to embrace it as I move forward.