Why I Hope the 'Lucifer' Showrunners Will Be 'Better Angels' When Depicting Disability

As a loyal “Lucifer” fan, I had been so excited to watch the show’s Season 5 (part 1) on Netflix… until I watched the first few minutes of episode 2, “Lucifer! Lucifer! Lucifer!” As the archangel Michael talks to himself in the mirror, we see his true nature, both physically and morally. Michael, it seems, is a modern-day Richard III, a worn-out caricature of a villain whose scoliosis and other physical differences are supposed to telegraph a corrupted internal nature.

I see Michael’s arm hanging carefully to one side. I notice how Michael puts his jacket on with the affected arm first. I hear Lucifer talking about his brother with the “sloped shoulder.” I can’t focus on the plot anymore. All I can do is look for other clues about Michael’s arm in the way he carries himself and moves. Does Michael have what I think he does? Is that really where they are going?

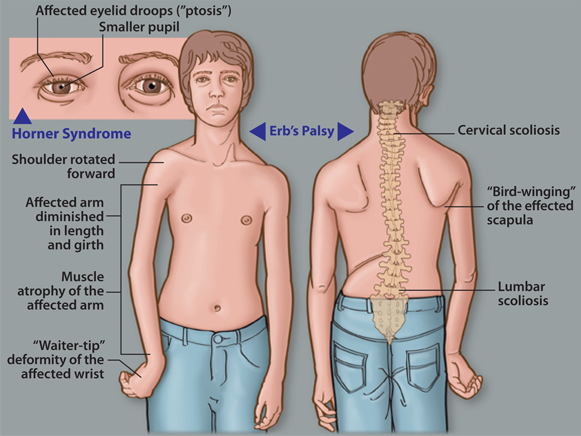

You see, I’m the mother of a 4-year-old child with an obstetric brachial plexus palsy (OBPI) — my daughter was permanently injured while she was being delivered. As a result, she has a paralyzed left arm and has undergone two surgeries, weekly therapy, dozens of braces and electronic stimulation therapy.

The injury impacts her entire body — her balance, her breathing and her core strength. She carries her unaffected shoulder higher than the other. She started to develop scoliosis because of her condition. She puts on her jackets and shirts by putting the affected arm in its sleeve first. But maybe this isn’t what the showrunners plan. Maybe they have something else in mind for Michael.

It’s just that I keep a close watch on arms. Most parents of children with OBPI do too. We know about legendary actor and jacket-flipper extraordinaire Martin Sheen and Super Bowl ring-wearing NFL player Adrian Clayborne. We look out for others who are like our kids, because OBPI is such a rare and stigmatized condition. Imagine explaining to a new acquaintance at a birthday party that your child was injured at birth, and that’s why she uses her mouth to open a gift bag.

We were once stopped in a restaurant by another OBPI family because they “couldn’t help but notice…” We shared a lot of hugs and tears over chips and guac that evening. A good friend of mine was pulled aside at her son’s track meet when another OBPI family noticed “how he was carrying his arm.”

Our children’s disability is sometimes easy to see, but hard to find in common with others. That’s why many OBPI families often have a sacred and almost immediate bond when they run into each other. That shared experience and support helps us to get through days when we experience overt discrimination, or the smaller, but also painful cuts that come from ignorance or lack of compassion in daily life.

Many OBPI parents I know will tell you that it hurts most when our children pick up on how they are different from other kids or when our children are actively excluded from things other children get to do. For example, watching a dance class not adapt choreography so your child can fully participate, or hearing another little girl wouldn’t let Eva on the tire swing with her because Eva had a “bendy arm.”

Children often want to know, why them? Whose fault was it? Why didn’t Mommy or Daddy stop the accident? If Mommy and Daddy are angry about the accident, does that mean that they are angry at their child? Mental health therapy can help to answer these questions and help parents deal proactively with the trauma of the birth accident.

As parents of children with disabilities, we must therefore be especially careful in what we expose our children to as they grow. We seek out and show them disability-inclusive entertainment like “Llama, Llama” and “Paprika” (also on Netflix and frankly, great shows for any child to watch to encourage inclusiveness, understanding and compassion). We take care to introduce them to positive examples of people with limb differences doing amazing things.

While Eva, at “4 and a half,” as she likes to remind me, is too young for “Lucifer” right now, there are many teens with limb differences who might be watching. I wonder what they think of Michael, and how Michael’s disability might make them feel when the whole world already tells teens to look a certain way to fit in.

Show writers Ildy Modrovich and Joe Henderson haven’t explained yet why Michael has, in an Entertainment Weekly reporter’s ill-chosen words, “a lazy arm.” They do say they feel Michael will be a hero at the end of the story.

I would simply ask that they consider everyone in their audience for their ultimate message. What has made “Lucifer” compelling entertainment from the beginning is the concept that good and evil are not so clearly defined by looks, stereotypes, or old-fashioned ideas. A demon can be a hero. The Devil himself can be a force for justice.

I hope that Season 5, Part 2, will speak to all of our better angels, those with disabilities and those without.

Image via Netflix.