Today, I find out if I have cancer.

A nurse called me last week to let me know that my mammogram findings were abnormal.

“Most such findings are benign (not cancer),” she said, “but it is important that you have additional evaluations as soon as possible. I’ll connect you to scheduling right now.”

She was eating her lunch. I was walking across campus to the parking garage. It was all very casual.

And yet my world has been spinning ever since.

The phone call I received last week wasn’t just about me, my health, my present, my future. It was also the echo of a call I received nine years ago.

“We saw something on the ultrasound. Most of the time it is nothing, but we recommend follow-up tests.”

Nine years ago, the call was about my pregnancy with my second child. After that call came a series of follow-up tests. The first confirming that I was positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV) — the most common viral cause of disability for babies infected in the womb, alongside reassurance that I was probably infected way before the virus could harm my baby. Then a series of more follow-up testing, leading to a final call from a prenatal genetic counselor to tell me that my results showed that it was impossible to pass the virus on to my developing baby.

My chart, which I printed off and is now kept safely with the growing volumes of my son’s medical records, says it was impossible for my son to be born disabled by CMV.

And yet when my son was born, he was so very incredibly symptomatic for infection with congenital CMV that he was proclaimed to be the mostest impacted CMV kid ever born in the state of New Hampshire that any one of his providers could remember. He’s a miracle, right?

Today, nine years later, I am the mother of three beautiful kids, inclusive of a child with 45 active coded conditions that resulted from that first one he acquired in the womb.

At this very moment, at least for a few hours more, I am also a woman waiting to hear news about my own health future.

And, I am also a professor at a medical school. In addition to anatomy and embryology, I think, write, and teach about communication in vulnerable spaces: students dialoging with peers, and teachers with medical students (who eventually become health care providers communicating with their patients). Most health care providers have very little formal training in communicating diagnoses, never mind the steps that come before the potential bad news. Medical school emphasizes curing and helping patients. Studies have shown that health care providers can feel they have failed the patient if a cure is not possible, and that sometimes these feelings result in offering false hope in a dire situation.

Words like psychosocial care and patient-centered communication are used as the goal, but what are the benchmarks for evaluating effective provider-patient communication in clinical settings? And who gets to decide on what those minimum standards are? Should it be the patient? Can it be?

After digging around in my patient portal over the last few days, I found a passage way down in the multiple pages of appointment instructions (where I’m guessing that many other patients probably never look) and buried in a jumble of other words that said that the results of my diagnostic imaging would be read and given to me immediately during my follow-up appointment. I instantly conjured up an image of me – alone, disrobed in a clinical room sitting on a cold hydraulic table covered in that crinkly white paper, surrounded by white coats, receiving a (potential) cancer diagnosis (knock on wood! spit spit!). I shuddered. This is not how I want to hear a life-changing, potentially life-limiting, diagnosis.

Elsewhere in my chart, it lists the other members of my family as a form of history. When looking at those names, I see more than just “Who else lives in the home?” — I see my partner and support person, the person who is supposed to be next to me on all steps of this journey. I see the people I care for and for whom I must arrange care if I want him to be at this appointment with me. Which I very much do. All of that takes time, planning and resources, especially for a family like mine.

I see the name of my medically complex child, and a deep well of distrust in the likelihood that everything is going to be OK springs up and overwhelms me.

Doctors are going to get the diagnosis wrong, sometimes. But once you have been the patient on the other side of those statistics those numbers don’t mean much to you anymore. And given that someone is always on the “wrong” side of those numbers, can’t the default conversation tool be empathy and support, no matter what the eventual outcome? Because even the psychosocial load of the imagined scenarios for the patient should be enough motivation to phrase that first call differently:

“The results of your tests were abnormal. We recommend follow-up. At the next appointment, your results will be read to you immediately. You can have one other person with you in the room if you’d like.”

What a difference those extra words would make for me now.

The “bad news conversation” is always the beginning of an extended journey for the patient. It should be that way for the health care provider, too. No matter what the eventual results, providers are in a unique position to partner with the patient to change the dialogue right from the outset. The conversation can be better. We can do better.

This is true, no matter what news I hear later today.

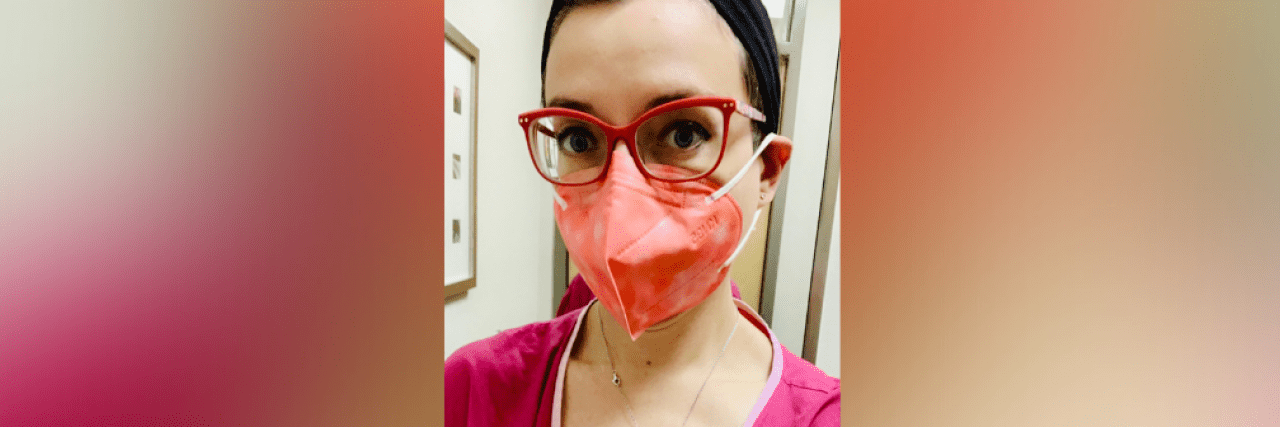

Image via contributor