Tell anyone that you live with a condition that makes you feel as if you are engulfed by flames every day, and they would assume your condition is a curse, through and through. To some extent, they would be right. Living with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a hefty burden to bear. My nervous system interprets all incoming stimuli as a red alert pain signal, be it light touch, sound, or genuine trauma. In addition to this, my brain spends so much time normalizing pain for me that it doesn’t have enough energy or focus to function like a healthy brain. This means it often drops the ball on other systems, which causes brain fog, loss of limb awareness, muscle spasms, tremors, and more. I live at a daily pain level of an eight or higher, and need the full time assistance of a service dog in order to function on a daily basis.

Now that you know all that, you probably think there is no way that I could possess anything but hatred for my condition. Except I don’t hate it, not completely.

I hate the pain. I hate when the spasms make me drop a cup. I hate that my life as a horse trainer got ripped away from me before I even had a chance to make a name for myself. I hate that the constant pain and unpredictable flare-ups means that it isn’t safe for me to drive. I hate that I’m 25 and already feel much older than my age.

Despite all that, though, getting CRPS has given me several gifts that I never would have experienced had it not been for the pain. One gift stands out among the others, and that’s what I want to share here.

Baseball. If you had asked me how I felt about baseball eight years ago, I would’ve told you that it’s a boring sport and a waste of time. If you ask me today, I’ll tell you a piece of my soul will always belong on a baseball field. I’ll tell you that I wouldn’t be who I am today if it weren’t for baseball. And I’ll tell you that my four years with baseball will always be some of the best years of my life.

In 2011, I stopped riding horses because the pain from my CRPS was too much to bear while riding and caring for horses. My whole life was about horses. I travelled 800 miles across the country to attend an equine college, I spent probably 12 hours each week at the barn, if not longer, and most of my friends were horse people. When I chose to stop riding, I felt like my heart had been shattered. I didn’t know where to go, what to do, or what to hold onto. To make it easier for me, I also stopped going to the barn, and didn’t want to hear my friends’ stories of good or bad rides. A few understood, but most of them shut me out for not “riding through the pain.” They told me I was weak, that I was a coward for not dealing with “a little pain.” I was abandoned by the only world I knew.

Around the same time, the marketing department at college started having me shoot sports games on campus for work study money. I grew up doing action photography of horses, so sports seemed like a good fit. The first baseball game I attended, I shot from outside the fence. I knew nothing about baseball. I didn’t know what positions to shoot, or where to look for action shots. I didn’t even know what constituted a “point.” I was completely baseball illiterate.

I turned in my shots to my supervisor the next day, and she was blown away. She shared my photos with the head of the athletic department, who was also impressed. I had stumbled into a natural talent. My timing was excellent, I captured the emotions of the players, and I shot stationary position photographs that were perfect for news releases. Before I even knew what was happening, I was placed in the dugout with the team, shooting every game that season.

Baseball became my new home. I bonded with the players over lunch, at practice, and at games. There was no where else I’d rather be. If the team had assigned study hall, I was sitting right there with them writing papers, reading books, or editing my photos. If there was outdoor practice, I’d be in the dugout or outside the fence trying out new angles, new lenses, and laughing with the guys. Over the course of four years with the team, I came to see many of the team as my brothers. They knew I was “injured” but that didn’t matter to them. What mattered to them was that I showed up, put forth my best effort, and was a damn good photographer. I caught moments of their college careers that they will forever be able to look back on and remember the good ‘ol days.

At that time, I didn’t have a diagnosis. Doctors were stumped. I didn’t even have medication to help me push through the bad days. I had ice (at the time I didn’t know that was a bad call), a wrist brace, a playlist of flare-up music, a team of brothers, and a whole lot of grit. On any given game weekend, I spent 14-16 hours total (Saturday and Sunday) shooting doubleheaders. The pain was only in my right wrist and shoulder at the beginning, but by the end of my baseball time it was in my ribs, back, neck, and jaw.

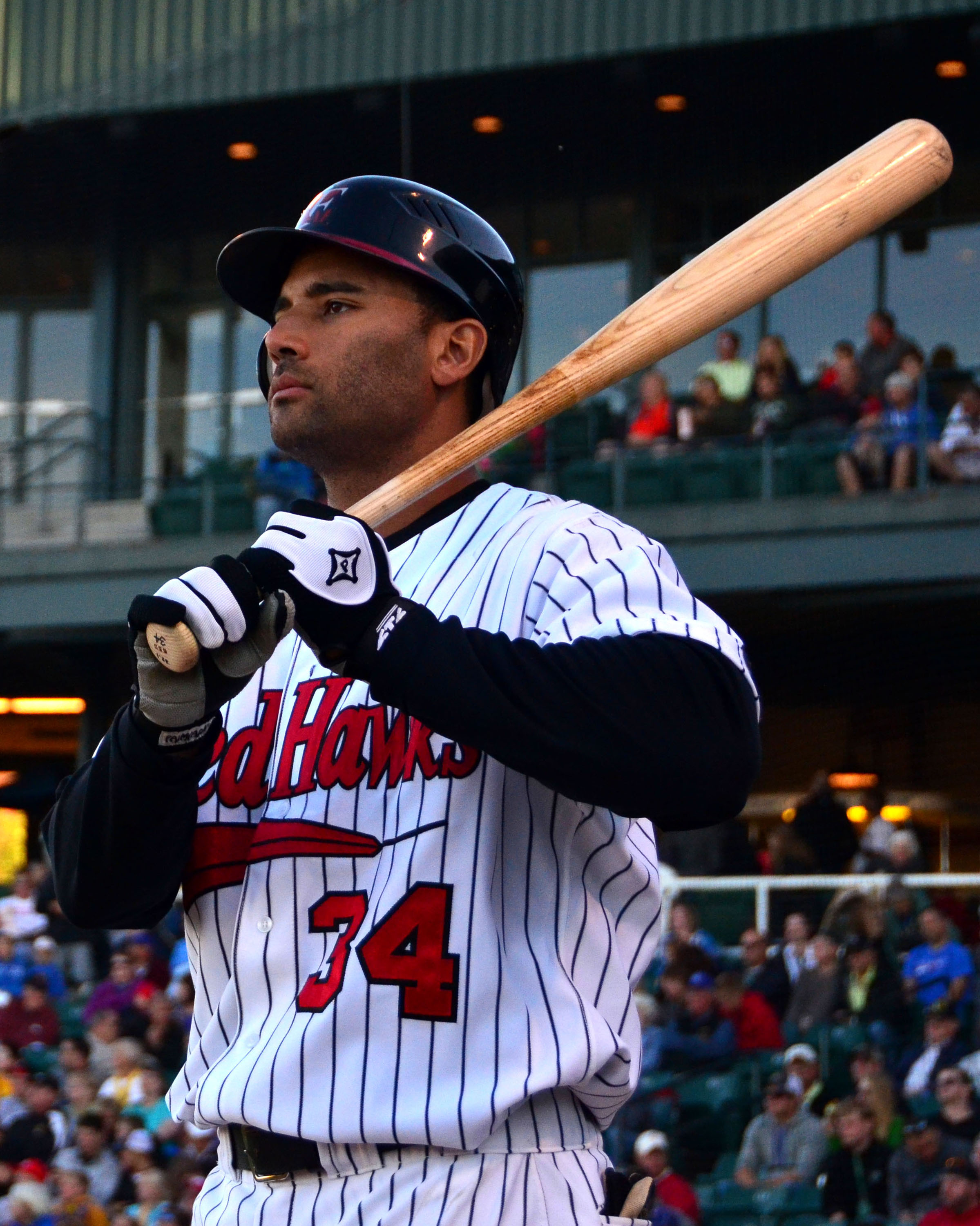

Since I couldn’t ride anymore, I decided I wanted to be a professional baseball photographer. In my free time, I studied the game photos of other professional photographers, and then would try to duplicate them as my way of learning. I asked our baseball coach to help me find baseball internships for the summers, and he did. I held two photography internships in college, one the summer after my sophomore year, the other after junior year. Both were incredible experiences, but the last one was the most profound for me because it wasn’t collegiate level…it was a professional team. It was there that I worked under a boss who was compassionate towards my pain condition, I made a new friend who became a sister to me, and found my ultimate happy place – shooting pro baseball from the roof of the stadium. All I have to do is close my eyes, and I am transported back to the roof at sunset, looking out over the entire field, and feeling totally at peace.

For four years, I dealt with the pain, and had experiences that can never be matched. While I shot for a total of three teams, my heart will always belong to my college baseball team. They are who I started with, who I grew with, who taught me the most about battling, and who helped me figure out who I was without horses. Coach told me once that if he could pay me, and keep me with the team forever, he would do so in a heartbeat. I made a little money selling photos to the team, but it was never about the money for me. Shooting through the pain, and dealing with the flare-ups later were all worth it to feel alive and whole for a few hours each day.

Remembering my time with baseball is remembering the laughter, the walk up songs, the goofy grins the players would flash me, the sarcastic comments in the dugout, all the foul balls that almost killed me, the concussion on the first base line that I kept shooting through despite the pain, staying up until 3 a.m. editing photos, all the miles I drove to be at away games, the taste of sunflower seeds on my tongue, the smell of fresh cut grass, the sound of turfs clacking on the concrete floor of the dugout, and the feeling of absolute calm right before a game started. It’s remembering the games we lost, and the games we won by a landslide. It’s remembering the times I was called a “good luck charm” or the first time I was called “a part of the team.” It’s remembering the day coach publicly recognized me as part of the team on senior day, when he gave me a black, Louisville Slugger with my name and position as team photographer engraved on the bat.

It’s been years since I shot baseball. After college I was offered an unpaid position shooting for a AAA minor league team in North Carolina, which was a huge deal. The public relations director wanted me based on my portfolio alone, and for a few weeks I rode the high that came with such an incredible offer. After much thought, I reluctantly turned it down because the pain was spreading and growing in intensity. I knew I would never have been able to withstand the pressure of shooting pro while juggling another job and severe chronic pain. By the end of my baseball career, I could barely hold my camera up for 30 minutes, and lost the quick reflexes for freezing the jaw-dropping action shots. Looking back, the pain was worth it. The spreading, the growth of intensity, and the loss of who I used to be as a horse trainer were all worth it because baseball gave me more than I dreamed possible.

Baseball taught me a lot. I learned great stamina for shooting. I learned to leave everything behind when I entered the field, because the right here, right now was all that mattered on game day. I learned how to internalize the pain, and then shut it out. I began learning how to accept help. I learned that I am more than a sum of my horse skills. I learned what it feels like to have brothers. I learned how to smile again. I learned how to battle.

Before baseball, I was raw, angry, and broken. The game, and the teams I worked beside sanded down my rough edges, restored my hope and ability to laugh, glued me back together, and showed me that I am capable of anything – especially the unexpected.