These past two months have been hard. Really hard, actually. I’ve been in a “grief spell” where the waves of grief have been unrelenting, towering over me and hitting me with full and merciless force. I’ve been through these periods countless times before but it never seems to get any easier.

Grief was a concept I only associated with bereavement: when someone you love dies. I never knew that grief was something we experience over any loss at all, regardless of how big or how small; and the depth to which we feel it is directly proportional to the meaning which that loss held for us.

Grief never sets in when we are “ready,” not that I even know what that would mean anyway. Who could ever be ready for the losses we endure in our lives? Losses of loved ones, health, friendships, relationships, work, opportunities, hopes, dreams. And as if the loss itself isn’t enough, life doesn’t ease up or pause to let us grieve the particular loss at hand. The needs of those around us and the problems of life do not stop. The left-field overwhelming stuff doesn’t cease to descend upon you at random. Relationships don’t suddenly get easier. People don’t get kinder or more thoughtful. Your partner still needs you to hear and support them. Your children still need to be cared for. Your friends are still going through shit that you need to be considerate of. There are still family events to go to or remember. Other people’s happy events and milestones that you need to celebrate. Appointments to attend. You still need to eat, shower, pay the bills, buy groceries, do the washing. F**k, life can be so relentlessly hard.

Grief doesn’t occur in isolation nor does it come alone. You would think that our brains would just focus on grieving the one loss at hand, but we don’t appear to work that way. Our brains hold a mass of interwoven memories, feelings, and thoughts; we rarely experience just one thought or feeling at a time. As it is, grief isn’t a “feeling,” it is a word we use to describe the mass of interconnected feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that occur when we lose something or someone. Somehow when we experience a loss it triggers this “web of losses,” especially the losses that devastated us the most, that we felt most deeply, that held the greatest meaning. They come back too and we feel them like we lost those things or those people just yesterday. And it makes sense, doesn’t it? Because when we experience a loss or a reminder of loss, we are acutely reminded yet again of the fragility of being human, of the pain we’ve endured, of our inherent vulnerability, of the risk we take when we love or care for someone or something, the risk being that it could all be taken away.

And grief brings its somber companions like depression, anxiety, and existential questions because when we experience loss we are reminded of the finitude of our being, the fragility of our happiness, the illusion of our sense of safety in the world, the erroneous assumption that we are “untouchable.” We are reminded of the vulnerability of our existence, that we can lose… again and again, in the most random of ways and the most awful and unfair of times. And these reminders can make us spin out, leading us to question what the hell life is all about, what the hell is the point… and does any of it even matter? And wow, is it a destabilizing and confusing process.

So, how the heck do you navigate it?

Well, you need to gently let yourself come to accept it, accept that it is here, and feel it — all of it, as often as it arises, for as long as it stays, with as much self-love and compassion as you can muster. There is no way but through when it comes to pain. We can’t avoid it (though we can avoid or deny it for an impressive amount of time, at a significant cost). We need to deal with it, walk through it, even if we can only muster crawling at times. And we need to surround ourselves with the sorts of people who will love and comfort us, empathize with us, and share in our grief.

Unfortunately, we can’t fast-forward the grievimg process. Even when you intellectually “know,” “ah yes, this is grief, I identify and accept this,” you still need to feel it emotionally and in your body — all of it. And you need to feel it for as often as it visits and as long as it stays, maybe hours, days or maybe weeks, months or years, but you trust that no matter how destroyed and empty you feel, feeling this pain is your path to healing it.

A Helpful Model of Grief and Healing

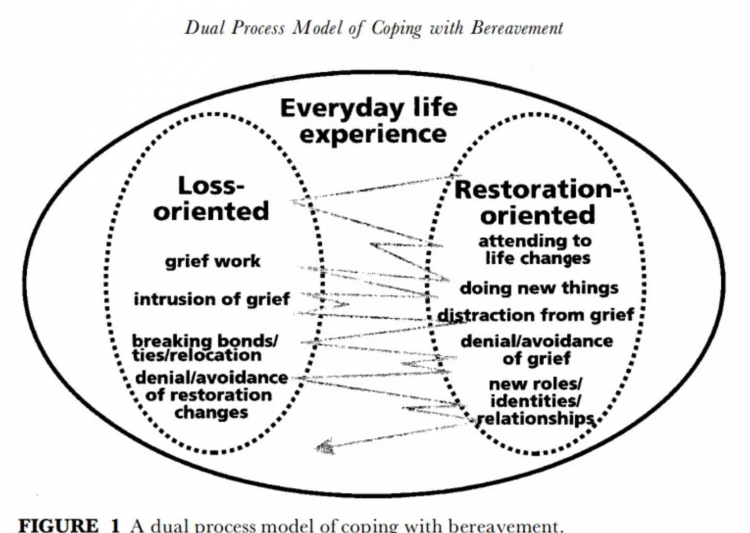

Though created as a model for grieving when bereaved, I have personally found Stroebe and Schut’s Dual Process Model of Grief to be one of the most helpful tools and perspectives for understanding and normalizing my own grief process.

In short, it describes how when we lose someone (or something), we oscillate between loss-oriented ways of living — which we would characterize as “typical grief” (sadness, despair, pain, agony, overwhelm, devastation) — and restoration-oriented ways of living , where we focus on rebuilding our lives. The key points are that:

- Grieving involves spending time in both places — grieving and re-building.

- We can’t control this oscillation, it occurs at random. Sometimes we can spend extended periods of time in restoration places feeling grand, just to then end up a week later back in loss places. It’s OK, it’s normal, and in time we learn how to better identify what “place” we are in. We ride the waves of grief instead of wasting energy fighting them, and we remember that as we do that, we will find ourselves back in restoration-oriented places again soon.

The Good

There are positives that can be found in the landscape of grief. I know that sounds contradictory, but it’s true. But most of these positives can only be found on the “other side” of working through our grief, of riding the waves, of bearing through the oscillations, of doing the work.

- We massively grow in our emotional intelligence. We learn to experience our full range of human emotions. We realize that we can hold 10 different feelings at a time and it is OK and it is normal.

- We come to be more understanding and accepting of others.

- We have more empathy.

- We feel more connected to others because not one person is immune from loss in this life.

- We peel back life, we peel back the layers of ourselves, we become more honest, we become clearer about what matters and who matters and what doesn’t and who doesn’t.

- We become more grateful and more present to what is.

- We love more deeply — both ourselves and those around us.

- We accept that we are never the same and are challenged to create ourselves anew.

- We realize that we can survive the darkness and that there is always some patch of light to be found, a patch for us to start again and re-create again.

I’ve come to deeply prize these things. I, like anyone else I’m sure, just wish I could short-cut the pain to be able to claim them more easily.

So will it ever end? Well, the short answer is no, I don’t believe we will ever truly “finish” all our grieving or “get over” our losses for good. And I think that’s completely normal and OK. For as long as we live and feel and love and are engaged in this world, we will risk and suffer loss, and we will grieve, and we will rebuild, re-grieve and re-build over and over again because that is what it means to live, that is what it means to be human. My hope is that we will love ourselves through it, through all of it, and that we will be able to share it, that we will learn to grieve and rebuild, together, that we will learn to help heal each other and find some peace and solace in that.

If you resonate with the things I write about, please follow me here.

This story originally appeared on Medium.

Getty image via Vladimir Vladimirov

This story originally appeared on Medium.