Imagine you have a linen closet that’s absolutely full. It’s stuffed full of linen, mementos and all of the embarrassing things you keep hidden from guests. You just received a new sheet set and some towels from your parents as a gift, and you’ve got a date coming over any minute for dinner.

In your haste, you shove the new stuff in the closet, displacing your other items and stuffing it in any way that it fits. You quickly slam the door before it sends everything tumbling out.

Your date arrives, but you can’t stop thinking about the linen closet that’s barely holding everything back. You imagine the door creaking under the weight of all of the extra stuff you shoved in it, and spend your date thinking about everything tumbling out and engulfing you. Every noise in the house sounds like the door giving way. You get worried when she excuses herself to the bathroom and has to walk past it on her way there. In the end, it was the threat of everything falling apart and the knowledge it was possible that ruined the date. It’s pretty easy to say in this instance that you should “just stop worrying” about it and accept whatever happens if your date sees the worst case scenario. But replace closet with brain, and linen with a life-threatening or traumatic event.

It becomes a different story.

This is not a bad descriptor of how living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can feel, especially for the most severe cases. How do you keep a life that is a constant, waking nightmare contained?

Basically this but in your brain, all the time, and you think everyone wants to open it.

Basically this but in your brain, all the time, and you think everyone wants to open it.

For those experiencing this debilitating mental trauma, this is one of the most constant fears, elevated social anxiety and distress, sometime even paranoia — caught between the dread that you are hurting and burdening people, or the dread that they will hurt you. For something so critical and destructive mentally, socially and physically, it is still massively misunderstood by the public, and still being fully researched and understood by neuroscience (like much of the brain and its function).

So, what are we talking about?

Far beyond anxiety and depression, it is defined as being triggered by an extreme stressor, such as:

- life or death events;

- exposure to harm;

- witnessing harm;

- learning of harming to a loved one or other forms of secondary exposure.

Its effects are greatly invasive — memory flashbacks, recurrent nightmares, severe emotional distress, physical reactivity and aversiveness of feelings, thoughts, situations and people. The person with PTSD will often avoid every triggering circumstance they can due to this aversion, which can leave them utterly trapped and lacking socially.

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash

Photo by Aarón Blanco Tejedor on Unsplash

The brain becomes reset in its cognition (thinking and processing) to function towards the negative at all times. This can include extremely negative and depressive thoughts about themselves and their world; memory retention, especially around traumatic events, becomes diminished or lost. They will likely blame themselves for everything, but especially their own trauma and suffering. In severe cases, impulsive aggression and fear or anger, and self-isolating behavior becomes more obvious and dominating of their mood, and they truly struggle to learn from, or experience positive feelings, thoughts and situations.

PTSD can fundamentally rewire the brain and how it responds to the outside world.

The way they react to the world is utterly altered.

Their whole world is fear and anger: out-of-context and explosive aggression, irritation or panic; increased risk-taking, destructive or self-destructive behavior; constant craving sensation or danger to contextualize what they feel; yet easily startled and panicked; diminished or destroyed capacity for focus, concentration and context; and disrupted sleep .

All of this is deemed in the DSM-5 (the standard textbook of mental disorders) to be a diagnosable, treatment-urgent state of PTSD if these symptoms are persistent for longer than a month and not caused by intoxicants of any kind.

Regardless of diagnostic protocols, this disease is utterly cruel and insidious, especially because it damages a person’s capacity for social connection and function. This is the exact thing they need for healing and support, as well as their occupational capacity, which is, over the long term, a requirement for stability and personal progress. Crueler still are the dissociation events, which only further limit the capacity to connect to help and realize a sense of safety and well-being.

Dissociation comes in two flavors:

- Depersonalization: An “out of body” experience of the most nightmarish form; being utterly unaware of, or unable to relate to, the self, separating the victim from their own experiences, needs and motivations.

- Derealization: or “the matrix effect.” The loss of their attachment to reality; disconnection from everything and their environmental needs and self-defenses; distortion of views and awareness.

And this is in no way a hidden, rare or untraceable, fringe disease. Many will experience PTSD in their lifetime.

So how do all these terrible things happen?

One of the most extraordinary factors of PTSD is the physicality of the disease. Actual physical, cellular damage is caused to the brain, the gut and the components of the nervous system — but most especially the brain.

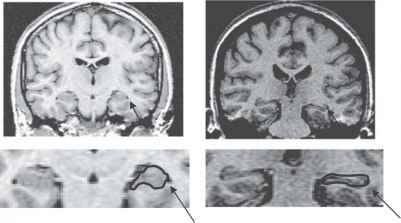

On the left, a healthy brain. On the right, the brain of someone with PTSD.

On the left, a healthy brain. On the right, the brain of someone with PTSD.

Grey matter degeneration: As you can see in the image, the grey matter of the brain is shrinking, areas of vital functioning — especially executive functions — are diminished and damaged. The greyer, faded appearance compared to the bright white of the healthy brain, speaks to a diminished neural density and quality. The brain is devouring itself in an overload of stress chemistry. The hippocampus (which is highlighted above) shrinks, and the amygdala goes into overdrive.

PTSD literally causes brain damage.

The hippocampus is responsible for forming new memories, spacial awareness, and much of the fight or flight response. The amygdala is responsible for decision making and emotional response.

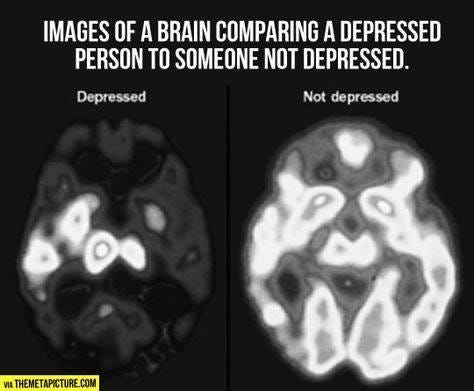

Images of a brain comparing a depressed person (left) to someone who is not depressed (right).

Images of a brain comparing a depressed person (left) to someone who is not depressed (right).

You can see in the second image the seriously deregulated and erratic signaling of a depressed brain… and PTSD is significantly more pervasive. Damage leads to the limbic system and amygdala hyperactively firing, erratically firing, or perhaps in extreme cases, not at all. The frontal lobe becomes powerless to regulate emotion. Fear, discomfort, anxiety and rage are the order of the day with no hope of relief without significant intervention.

This depersonalization leads to a horrific consequence of PTSD, especially for victims of domestic/family violence: they literally lose their voice. Beyond losing their sense of personal integration and identity, a key language centre shuts down. During a recall of a traumatic event, or a re-exposure, many literally cannot speak. Thus so many survivors speak of “speechless terror.”

Unsurprisingly, with so much physical trauma to the brain you can see the results in those living with PTSD: fearful, depressed or “vacant” affect; daydreaming or shut down events in public; shaking and tremoring; explosive or panicked reactions to any new stimulus and more.

Article originally published on reflex.org.au

Photo by Nik Shuliahin on Unsplash