Editor’s note: If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. This piece also references a gay slur and discusses violence. If you need support now, you can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741-741.

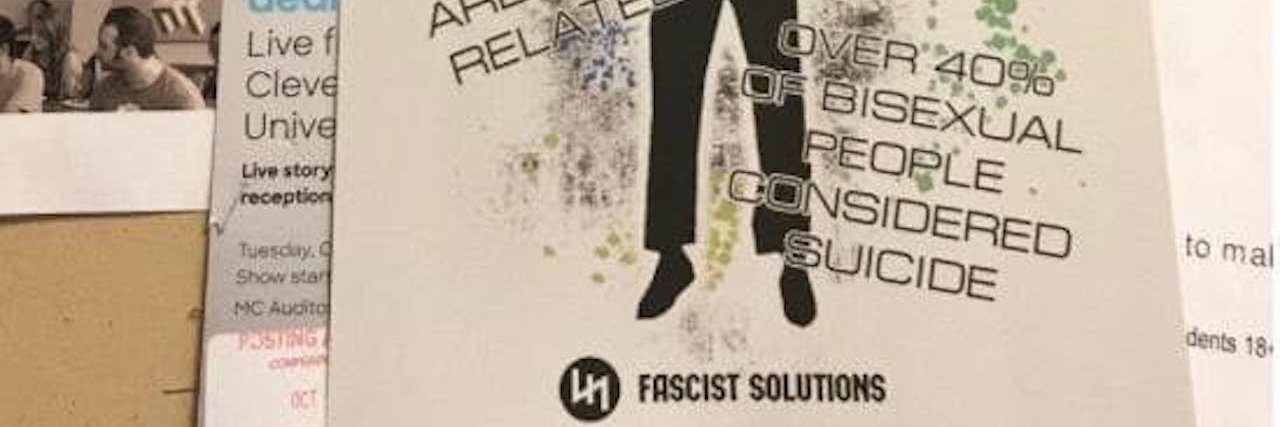

It sounds harsh, and it may feel wrong, but telling someone to kill themselves is technically protected by the First Amendment. Of course, just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s not hurtful, or even dangerous. Students from Cleveland State University learned this when their school refused to take down hateful anti-LGBTQ posters hanging on campus, citing that because CSU is a public university, they were protected under the first amendment.

this isn't upholding of freedom or neutrality @PresBerkman this is cowardly endorsement of violence and there will be blood on your hands pic.twitter.com/TbqXzaCIIF

— jack ???? (@Pamtre_) October 17, 2017

The posters used suicide statistics to encourage people in the LGBTQ community to die by suicide, with the text: “Follow Your Fellow F*ggots.” When concern was raised about the hateful message, CSU President Ronald M. Berkman sent an email to the university:

Dear Students, Faculty and Staff,

At Cleveland University, our foremost priority is maintaining a welcoming environment that provides opportunities for learning, expression and discourse.

CSU remains fully committed to a campus community that respects all individuals, regardless of age, race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation and other historical bases for discrimination.

CSU is also committed to upholding the First Amendment, even with regard to controversial issues where opinion is divided. We will continue to protect free speech to ensure all voices may be heard and to promote a civil discourse where educational growth is a desired result.

Be assured that a spirit of inclusiveness will always be central to the very identity of our University.

Many students thought his response lacked compassion, and some claimed “protecting the First Amendment” wasn’t reason enough to keep the posters up.

CSU: this is a disgrace and you should be ashamed of your inability to support and protect your students.

— Stephanie Haught ???? (@smhaught_art) October 17, 2017

this isn't upholding of freedom or neutrality @PresBerkman this is cowardly endorsement of violence and there will be blood on your hands pic.twitter.com/TbqXzaCIIF

— jack ???? (@Pamtre_) October 17, 2017

I am aghast that you are implying that free speech protects speech that invites causing harm, it doesn't, you are failing your students.

— Adam Philip (@AdamMPhilip) October 22, 2017

Your defense of this hate speech, makes you complicit. You've abandoned your responsibility to protect your students.

— Jamie The Human ????????????????️???? (@jcooper311) October 21, 2017

While CSU hasn’t responded to The Mighty’s request for comment, Berkman shared a second statement with students after the negative reaction to his initial one.

He wrote:

I wanted to acknowledge that yesterday I failed to express my personal outrage over a recent incident involving an anti-LGBTQ+ poster that was recently posted on campus.

While I find the message of this poster reprehensible, the current legal framework regarding free speech makes it difficult to prevent these messages from being disseminated.

Dear CSU community, please join me for an open meeting tomorrow to discuss a recent incident involving an anti-LGBTQ+ poster on campus. pic.twitter.com/ae1u7wBty3

— Ronald M. Berkman (@PresBerkman) October 17, 2017

According to David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing free speech, Berkman’s statement is technically right — as horrible as they are, these posters are protected under the First Amendment.

“Hate speech doesn’t have a definition under the law, but I think what most people think of as hate speech is protected under the First Amendment. The mere fact that something is hate speech doesn’t mean that we can silence it,” Snyder told The Mighty.

According to Snyder, we tend to forget how broad the First Amendment is partly because of how much time we spend on social media. While Twitter and Facebook both have their own definitions of hate speech and guidelines about what can and can’t be posted (although one could argue they’re not great at enforcing them), a public university has to play by the government’s rules, and technically, telling a group of people to kill themselves isn’t against the law, no matter how deplorable it may be.

When You Can Be Held Accountable for Someone Else’s Suicide

In August, a 17-year-old named Michelle Carter was found guilty and sentenced for her role in the suicide of her boyfriend Conrad Roy III, who died in 2014. A series of text messages showed Carter had repeatedly urged her boyfriend to kill himself, and then did nothing when he was in danger. This case is different then the anti-LGTBQ posters, Snyder explained, because of the specificity of the situation and the language. Telling someone to die in the comments on YouTube is different than targeting an individual in such a way that their death can be traced back to your commands and actions.

In a column on Verdict, Sherry F. Colb, a professor at Cornell Law School, explained why Carter’s actions weren’t protected by the first amendment:

If she had written an essay or a book arguing either that suicide in general or her boyfriend’s suicide in particular was warranted, that writing would be protected by the First Amendment, and she could not be criminally punished for producing it. Does a text message receive less free speech protection than a book or an essay? In principle no, but in context, the immediacy of the text makes a difference.

If Carter was simply expressing her viewpoint that Roy should die by suicide, her opinion would be protected by the First Amendment. But, Colb says, inciting imminent violent, like ordering a person with a gun shoot someone, is not protected by the First Amendment. Because Carter repeatedly urged Roy to kill himself and helped him research a method, her words go beyond expressing an opinion.

“Saying ‘shoot him now; it’s the best thing’ is not protected by the First Amendment, even though an essay on the benefits of murder would be protected,” Colb added.

In another case back in 2011, a 47-year-old man named William F. Melchert-Dinkel was charged with two counts of aiding suicide. Melchert-Dinkel, pretending to be a woman, found vulnerable people online and encouraged them to take their lives, going so far as to tell them which methods worked best, the New York Times reported. According to court documents, he had likely encouraged dozens of people to kill themselves.

But those charges were overturned when in 2014 with the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled that “advising” or “encouraging” a suicide is protected by the First Amendment. But, in Minnesota, assisting a suicide is illegal, and eventually, Melchert-Dinkel was charged with “assisting” a suicide.

“Encouraging” vs “assisting” may seem like a subtle difference in language, but under the law, it differentiates between what is an expression of free speech and what is a crime.

Why Isn’t It Illegal to Tell Someone to Kill Themselves?

Twitter user @graysonearle wrote in a response to the anti-LGBTQ posters, “You see a poster like that and your first instinct is to defend freedom of speech?”

Snyder said people typically argue that government and public institutions should regulate this kind of speech… that is until someone they don’t agree with is in charge.

“You might be in the majority now, but what’s regulated in Alabama might result in something very different than what is in California,” Snyder said. “If you’re a liberal, do you want Donald Trump to be defining what hate speech is?”

But many universities do have speech codes that aim to fight against instances of hate speech. According to first amendment scholar David L. Hudson Jr., many of these codes are based on what is called the “critical race theory” of free speech — which argues unrestricted free speech does not adequately protect minorities, and that hate speech discourages minority voices, therefore infringing on their First Amendment rights.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education says that speech codes prohibit speech based on content and viewpoint, arguing, “If universities applied these rules to the letter, major voices of public criticism, satire, and commentary would be silenced on American campuses.”

Where does telling someone to kill themselves come into all of this? First Amendment advocates argue that although universities should be able to put reasonable restrictions on what, for example, gets hung on a college bulletin board (how big a flier can be, how long it is allowed to be posted), content-based restrictions set a precedent we might not want to set, depending on who defines what is considered “offensive” and what is not.

On the other hand, sociologist and legal scholar Laura Beth Nielsen pointed out in a piece for the Los Angeles Times that treating hate speech like “just speech” ignores the real negative physical and mental health outcomes hate speech can cause. While we don’t quite know yet if bullying directly causes suicide-related behavior, we know they can be closely related. Nielsen wrote:

Hate speech is doing something. It results in tangible harms that are serious in and of themselves and that collectively amount to the harm of subordination. The harm of perpetuating discrimination. The harm of creating inequality.

What We Can Do When This Happens in Our Communities

When something like this happens on a campus or a community, we can’t cry “free speech” and be done. While legally Cleveland University’s response was “adequate,” and didn’t promote the speech, it could have gone further in addressing how hateful the message was. As the saying goes, “fight speech with more speech.” This can be especially important when it comes to messages that target an already at-risk population.

According to the Trevor Project, LGBTQ youth seriously contemplate suicide at almost three times the rate of heterosexual youth and are almost five times more likely to have attempted suicide.

“If we see something that’s offensive, even if it’s protected by the first amendment, it does have an impact on campus climate,” Raja Bhattar, Director of the LGBT Campus Resource Center at the University of California, Los Angeles told The Mighty. “If there’s only one message, that’s 100 percent of what you see. But if the hateful message is only one message out of 100, it’s only 1 percent. That’s one way we can protect free speech, but also protect students.”

This means not simply disapproving of speech, but actively overshadowing it — making it clear this kind of speech isn’t welcome. For example, this could mean posting supportive posters next to hateful ones, or in this particular case, making sure the numbers for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255) and the Trevor Project’s lifeline (1-866-488-7386) are readily available.

Even if you can’t physically take down a hurtful poster or prevent people from saying, “You should kill yourself,” we can make sure communities have adequate resources for people who are potentially affected by these messages. This means fighting for accessible mental health resources and actively engaging with people who are suicidal to make sure messages of hope permeate through messages of hate. We can’t let the hate of a few overcome the love and support many can provide.

If you or someone you know needs help, visit our suicide prevention resources page.

If you need support right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, the Trevor Project at 1-866-488-7386 or reach the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741-741.