This year would have been my dad’s 25th Father’s Day. Even though I had only talked to him once in the year before he passed away, I know above all else, he took the most pride in his kids, and there was nothing he loved more than me and my brother. Sometimes it was hard to remember this, as he became increasingly difficult to talk to. The last time I spoke to him, I was pissed off, but before I hung up the phone, I told him “I’m so angry at you, but I love you,” his voice softened and he replied, “I love you, too.” This is the only comfort I’m left with — the knowledge that he knew I loved him, that he loved (and still loves) me, and that he is finally at peace.

A little more than a month after this, on April 4, 2016, my dad — the man who never tired of kayaking, golfing and cracking jokes — died by suicide.

I grew up surrounded by words like Lithium, Antabuse, Zoloft, Seroquel and Abilify. The names of medications swirling around in my adolescent brain. The older I got and the more I understood, the more afraid I became. I denied my own mental health issues. I was angry, frustrated, sad, confused. I didn’t understand why Dad couldn’t take his medication like he was supposed to. Why he couldn’t give up drinking. Why he would lie to the ones he loved. Why he couldn’t do what he was supposed to so he could get better.

I cried when my mom had to explain what ECT was. I cried every time Dad had to pack his suitcase and stay at the hospital. I cried every day for weeks after he died. Cried so hard I almost vomited. Body-wracking sobs. I cried when people found out but no one called. When it felt like no one cared that he was gone or how much I was hurting. I cried when I was blamed for him taking his own life. I cried for my mom’s pain and my brother’s pain, as it was left unvalidated. I cried for all of the things he would miss. I cried for myself and then felt selfish. I cried for how much he had hurt and how badly he had wanted to be happy. I cried because I don’t know that he ever was.

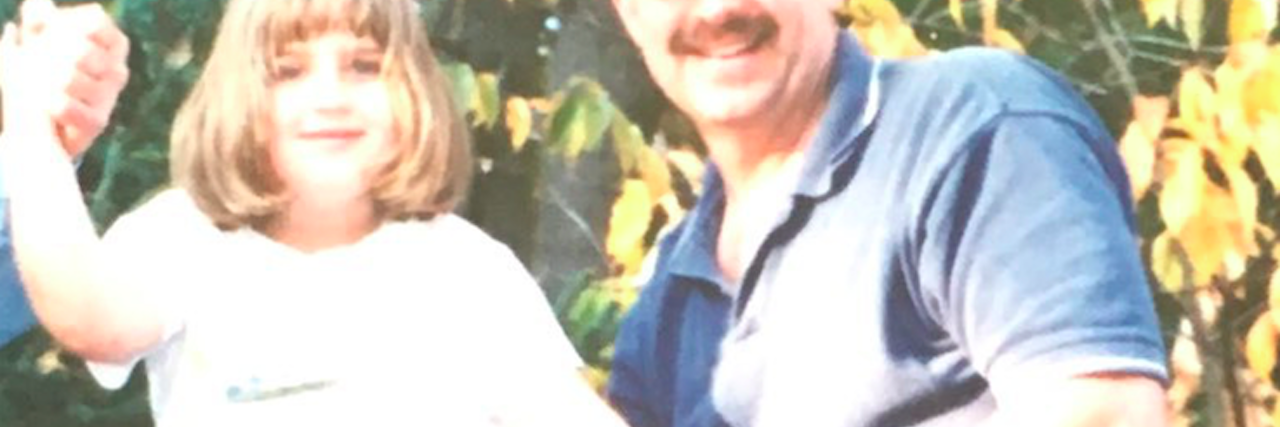

As a kid, he was my hero. He was funny and weird. He loved his family. He could build doghouses and birdhouses and fill bike tires. He coached soccer teams and had a nickname for his car. He could walk along the bottom of the pool and made up songs. He carried me inside when I broke my leg and took great pride in his tuna-noodle casserole recipe. He loved grilling, spending time outside and sitcoms. He gave me his green eyes and ridiculously curly hair. He had crooked pinkies and a dimple in his chin — both of which I inherited. He frequently found reasons to remind me my sense of humor was one of my greatest gifts, and he wore his Emerson sweatshirt every time he visited me at school. My hero.

Here’s the thing: heroes aren’t immune to pain. Maybe it’s worse for them. They’re supposed to be strong, to help provide for their family; heroes aren’t supposed to feel broken. They’re not supposed to struggle to get out of bed, to need meds to help get them through the day. That’s what the world told him and he believed it. The thing about believing you’re not allowed to hurt is that you also believe you’re not allowed to get help. You might even believe you’re not worth the help you’re offered. I wish he had known I wasn’t ashamed of his illness and that I would have been proud of him for getting help. One of the things I admired most about him was that despite all of the pain he felt, he kept living.

I wasn’t ashamed, but he was. He didn’t want anyone to know. He tried to hide it. My childhood was filled with cancelled plans, white lies and excuses to friends of the family, leaving early. I didn’t invite friends over and I didn’t leave the house if that meant leaving him alone. I isolated myself because I believed I could make him better. I spent much of my life trying to save him. I wanted him to live so badly and believed his life was my responsibility. My greatest fear for as long as I can remember was that he would take his own life. I’m adjusting to a life where my greatest fear has come true.

Pushing someone to live when they don’t want to is draining. I would have done anything to save him. There came a time when — after therapy sessions, my own mental health diagnosis, years of taking my medication as prescribed, after my parent’s divorce and going away to college — that I realized I could help him but I couldn’t make him live. It was both terrifying and a relief.

Every day is a struggle to accept his life wasn’t my responsibility and his death wasn’t my fault. It’s trying to remind myself my mom, brother and I tried so hard, for so many years, to help him get better and make him happy. That it wasn’t his choice to leave me. That he wanted so badly to stay, to be better. That his death was not selfish. That his intention was never to hurt the ones who loved him. It’s adjusting to talking about him in past tense. It’s meeting new people and realizing they’ll never know him. Thinking about a future in which he doesn’t exist. Reminding myself his demons are not mine. Remembering I am worth taking care of, worth being helped, worth loving. It’s a constant push towards believing I am enough.

Suicide, depression, and bipolar disorder took the man who was supposed to watch me graduate, walk me down the aisle, make a toast when my brother gets married, hold his future grandchildren. I was supposed to introduce him to new friends, and eventually, to the man I will someday marry. He was supposed to hear the joyous chorus of “Grandpa!” at family celebrations. He was supposed to remind me to keep my sense of humor, even in my darkest days. He was supposed to be on the other end of the phone when I dialed his number. He wasn’t supposed to be buried by his children, brother and parents less than four months after his 55th birthday. Wasn’t supposed to be eulogized by a woman who couldn’t even pronounce our last name. The forever goodbye was not supposed to come so soon.

Now, a little after two months after his death, I had to face the holiday that was dedicated to celebrating him. I watched as Facebook friends posted pictures of their dads. I was jealous. And I’ll admit it — this post was for me. It was selfish — something I had to write. But it’s also for him and the countless others who lost their fight. I refuse to let his life end with his death. It’s for the people still struggling. For the families and friends who lost and for those who will lose someone too soon. I wrote this because I won’t be silent — I can’t be, because silence is deadly. To cut myself off from the world, to lie about how I lost my dad, that would be selfish. I will shout from the rooftops that he suffered, that he could’ve been saved. I will write and talk about suicide and mental health. I will point out the disgusting lack of mental health resources and the cuts to funding. I will fight the stigma and remind people they are worth every good thing that happens to them, and that the bad things don’t define them. I will tell anyone who will listen that every bad day passes, that everything gets better. I will share my story so no one feels alone. On Father’s Day, I went mini-golfing with friends — a way to feel close to my dad on a day I wish I could spend with him. I celebrated his love of golf and the happy childhood memories that are now bittersweet. And then, on Facebook, I posted a picture of Dear-Old-Dad.

If you or someone you know needs help, see our suicide prevention resources.

If you need support right now, call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.