In Rural Utah, Preventing Suicide Means Meeting Gun Owners Where They Are

Editor's Note

If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

A gun show might not be the first place you would expect to talk about suicide prevention — especially in a place like rural northeastern Utah, where firearms are deeply embedded in the culture.

But one Friday at the Vernal Gun & Knife Show, four women stood behind a folding table for the Northeastern Counseling Center with precisely that in mind.

Amid a maze of tables displaying brightly varnished rifle stocks, shotguns and the occasional AR-15 assault-style rifle, they waited, ready to talk with show attendees.

“Lethal access to lethal means makes a difference,” said one of the women, Robin Hatch, a prevention coordinator with Northeastern Counseling for nearly 23 years.

Utah has one of the highest rates of suicide in the U.S. And from 2006 to 2015, 85% of firearm deaths in the state were suicides. According to Utah’s health department, suicide rates vary widely by location. For example, the suicide rate in this corner of Utah is 58% higher than the rest of the state.

Suicide by gun is a particular problem: The rate in rural areas is double that in urban areas, according to state officials. A major factor is the easy access to firearms in Utah — and the grim fact that suicide attempts involving guns have a higher mortality rate than by other means.

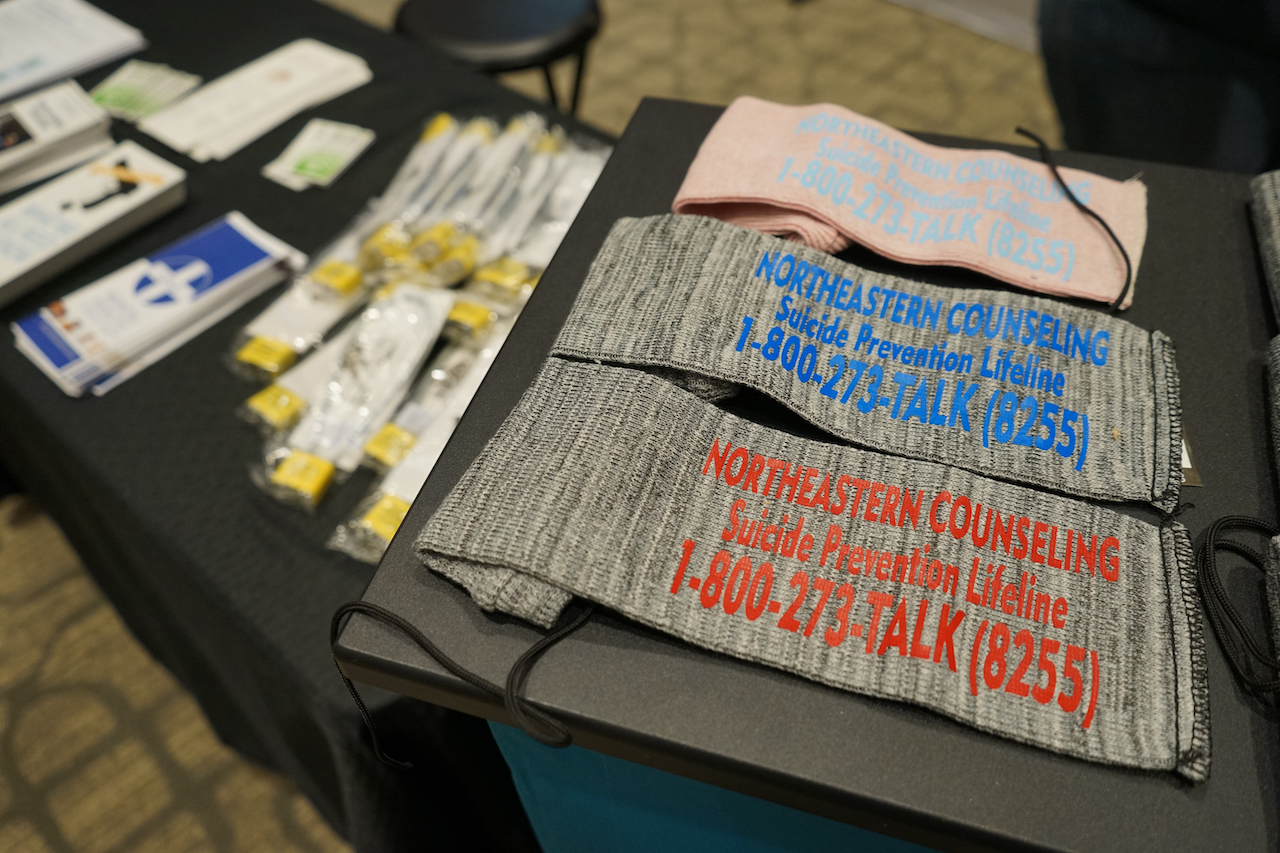

This was the first time Hatch and her colleagues at Northeastern Counseling did outreach at a gun show. As the auditorium filled with firearm sellers and hunters, the counselors stacked their folding tables with neat piles of free cable locks that thread into a gun to prevent rounds from being loaded, and water-resistant gun socks screen-printed with the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number.

The idea behind distributing both devices is to slow a person down during a moment of crisis. “Anything that we can do to get people off track a little bit, thinking something different,” Hatch said. “We believe that will help make a difference in our suicide rates.”

Unpredictable Employment Adds Stress

Northeastern Utah is home to oil and gas fields, cattle ranches and the Uintah and Ouray Indian reservation.

Health experts say factors contributing to the area’s high suicide rates include limited access to mental health services in rural communities and the unpredictability of the ranching and oil and gas industries. The boom-bust cycles, along with physical and mental stress, take a toll on workers.

“Injuries and accidents, keeping your job, having a job tomorrow — it’s so up and down,” said Val Middleton, a former oil and gas safety instructor at Uintah Basin Technical College in Vernal. “The guys don’t eat right, typically. No exercise, hard work, long hours, no sleep. That’s what adds up. The divorce rate is high, really high. The family life is low.”

Add high gun ownership and the risks rise.

Dee Cairoli is the pastor at Roosevelt Christian Assembly in a nearby town. He also works part time as an NRA concealed-carry handgun instructor. When hosting classes, Cairoli explains how gun owners can intervene if another gun owner shows signs of a mental health crisis.

“I’ve done it a couple of times as a pastor where I’ve gone to somebody’s house and said, ‘Look, maybe you need to listen to me for a minute. I know what I’m talking about. I promise I’ll keep it in my [gun] safe, but let me have your gun.’”

Cairoli speaks with authority. When he was 15, his father killed himself with a gun.

“It was very tragic, but I never hated the gun. I never blamed the gun. I knew that it was just his desperate moment and that he had just chosen that,” Cairoli said.

He believes that personal tragedy, along with the credibility he brings as a gun user and local pastor, allows people in crisis to trust him.

Not Just A Rural Issue

How to talk about suicide with guns isn’t just an issue in rural Utah. It’s a topic that state Rep. Steve Eliason of Sandy, a large Salt Lake City suburb, also tackles. The Republican has sponsored legislation focused on firearms, suicide prevention and mental health services. It is personal for him, too.

“I’ve lost three extended family members to suicide. All firearm suicides. Young men,” Eliason said.

This year, he worked on bills to fund firearm safety and suicide prevention programs, supply gun locks, create new mental health treatment programs and expand crisis response in rural Utah.

Eliason describes these issues as nonpartisan, but with Utah’s proud gun culture, he’s also careful with his approach. He describes advice he got from a politically liberal friend in public health about how to bring together opposing perspectives about firearms.

“Obviously, there’s kind of two schools of thought on firearms,” he said. “Those two schools of thought, if they were circles, they would overlap into a small oval — that oval is the culture of safety. And she says, ‘I would recommend that you dwell within that oval.’ That’s what I’ve tried to do.”

That perspective led the Utah legislature to appropriate money to fund a study by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in consultation with the Utah Shooting Sports Council.

That study spurred discussions about the problem of firearms and suicide and formed the basis of at least one of Eliason’s 2019 bills, to expand access to gun locks.

Like Eliason’s work at the state policy level, Hatch’s suicide prevention work in her community depends on relationships and trust.

Hatch’s table at the gun show was less busy than others. But the women gave out hundreds of gun locks and gun socks over the course of the day. And attendees said having them there was a fitting way to bring up the subject of suicide and firearms.

“You need to know your community, and you need to address it in a way that your community will accept it,” Hatch said.

If you or someone you know has talked about contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or use the online Lifeline Crisis Chat, both available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

This story is part of a partnership that includes KUER, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Photos by Erik Neumann/KUER