The People Suicide Prevention Leaves Behind

Sometimes the news isn’t as straightforward as it’s made to seem. Sarah Schuster, The Mighty’s mental health editor, explains what to keep in mind if you see this topic or similar stories in your newsfeed. This is The Mighty Takeaway.

Editor's Note

If you experience suicidal thoughts or have lost someone to suicide, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact the Crisis Text Line by texting “START” to 741741.

Every September during National Suicide Prevention Month, nonprofits and organizations alike make hashtags, create campaigns and hold events to spread awareness about suicide prevention. It’s a beautiful thing (The Mighty does it, too), and with the rise of social media, those who lead these efforts can reach mass amounts of people like never before, spreading information, resources and messages of hope to people who might not otherwise see it.

Still, we must face an uncomfortable truth: the suicide rate hasn’t been going down. Despite how great suicide prevention campaigns can be, their viral nature doesn’t leave much room for specifics and nuance. And despite all the good the internet has done, it can’t reach everyone, and it may, in fact, leave out groups of people who need suicide prevention the most.

Here, we want to explore some of the people who sometimes get left behind from mainstream suicide prevention campaigns. This article doesn’t cover everybody — not even close. But we hope it serves as a reminder that we can’t keep approaching suicide prevention with a “one size fits all” solution. These folks also need information, personalized resources and messages of hope — and we need to do a better job reaching them.

The Overlooked

Although Shawn Henfling says he lived with depression before he had the language to talk about it, it wasn’t until the age of 35 he started thinking he’d be better off dead.

Henfling was the “smart one” in high school. A guy people said had potential. But when he looked back at his life, all he could see was potential lost. At 35, he was living paycheck to paycheck working at a job he didn’t like. He had a family but couldn’t shake the feeling he was a terrible husband and awful step-parent. He was so miserable at work and at home, he would often stop his car mid-commute, not sure which destination he dreaded more.

“None of it fit,” he said. “It was a like having a 1,000-piece puzzle, and every piece was from a different puzzle.”

For men like Henfling, who intellectually know times are changing — that it’s OK to make less than your wife, OK to not be strong all the time — it’s still hard to unlearn society’s expectations.

I had no identity of my own. For guys, your job is your identity, and when you hate your job or when you don’t feel like you fit in, you don’t have anything… I didn’t see myself as a good parent, I didn’t see myself as a good father. I wasn’t filling those traditional rolls. It didn’t matter that my parents didn’t really have those traditional roles, it didn’t matter that I was consciously aware that we don’t have to fill those roles. It mattered that for 35 years watching TV, listening to the radio, reading a magazine, that’s what I internalized… You see it everywhere, it doesn’t matter.

Men accounted for seven out of 10 suicides in 2016. Whether rooted in unaddressed depression, difficulty finding their place in an ever-changing world, a combination of both — or likely, a combination of both and more — Shawn is one of the many men who faced suicidal thoughts as he crept towards middle age. In 2016, the highest suicide rate was between ages 45 and 54.

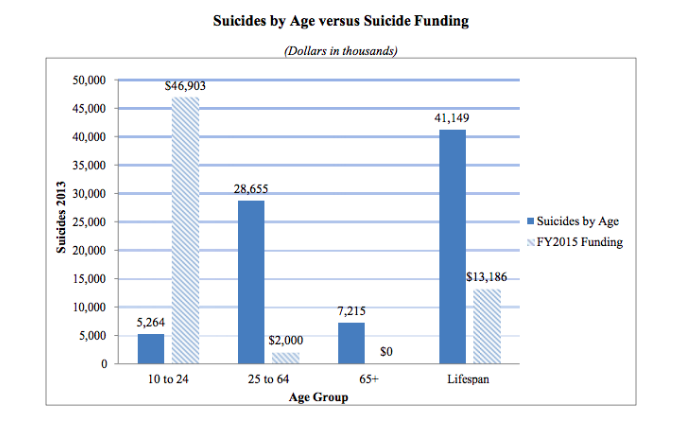

Most of the money spent on suicide prevention is geared toward people who are younger. For example, in 2015, The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) spent over $46,000 on suicide prevention targeted at ages 10 to 24 and $2,000 for ages 25 to 64. No money was spent for people over 65, even though the second highest suicide rate occurred in those 85 years or older. While it’s important to target suicide prevention at young people — after all, early suicide prevention may prevent attempts later in life — we’re largely ignoring a group of people who are dying too early.

Depression and despair can look different on men, coming out not as overt sadness but sometimes in bursts of anger or reckless behavior. This, along with the fact that men are less likely than woman to ask for help, could account for why men get diagnosed with depression at half the rate than women. Gender bias like this hurts everyone. Doctors are more likely to diagnose women with depression — but might overlook other symptoms like pain. A man, on the other hand, is less likely to be diagnosed with depression, even when he presents similar symptoms as a woman’s.

Men are also more likely than woman to use lethal means when they attempt, so by the time those around them realize there’s a crisis, it might be too late. Men who try to kill themselves with a gun have a one in 10 chance of surviving.

The Bypassed

Middle-aged men at risk of dying by suicide are more likely to live in rural communities, where the “cowboy mentality” of rugged independence meets inadequate resources and funding. The suicide rates in rural counties are higher than anywhere else in the country, affecting not just white men but Native Americans as well.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, the gap in the suicide rates between rural and urban areas is growing, and currently, the suicide rate for agricultural workers is five times higher than the general population.

Rhianna Brand, Director of Operations at Grace for Two Brothers, an organization dedicated to suicide prevention in Wyoming, says like many in the suicide prevention field working in rural communities, “We’re all doing seven jobs.” Wyoming had the third highest suicide rate in the U.S. in 2016, and there’s not enough people or money to go around.

“I think that’s pretty consistent if you’re in a rural area anywhere,” Brand said. “There’s just not enough humans to do what needs to be done.”

She says while national groups like the American Foundation of Suicide Prevention (AFSP) have donated resources for certain projects, like bereavement packages for those who have lost a loved one to suicide, AFSP’s big funding events, like Out of the Darkness Walks, are harder for communities like hers to pull off. Usually, half of the funding raised from these walks goes to the national chapter, and spending time to raise funds that will be filtered out is not a luxury her community can afford.

Brand called the state of her local inpatient hospitals horrendous. (“You’re not even allowed to bring your own underwear anymore… It’s literally like you go into prison.”) There also aren’t enough beds. Lately, when she responds to calls about people who died by suicide, she hears the same story over and over again: They were just released from the local psychiatric hospital, they were someone’s former patient, they had been to the ER two weeks ago. Although one and a half million dollars were granted this year for suicide prevention services across Wyoming, this is only after $2.1 million was cut from last year’s budget.

“The national organizations are wonderful,” Brand said, “But I’m really getting tired of people not listening.”

People don’t know. They are so far removed from the situation of rural areas because they’re in a metropolitan area, and all they see are these numbers. But they’re not in it. They’re not seeing the lives that are affected, how much of an impact this is having, how much money it’s costing our state. People are dying. And the system is failing seriously.

For both Henfling and Brand, growing society’s “awareness” of suicide prevention has left their communities overlooked. Henfling said while it matters men like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson have spoken out about depression, for some already in middle age, the awareness is coming too little too late. Many people his age aren’t as attuned to social media, where some suicide prevention campaigns take place.

“Even though society has changed, it takes a long time for people to change,” he said. “The last 10 years in mental health from a societal view have been the most important in the last 50… But we’re not as connected as younger people.”

For Brand, the money being pumped into national suicide prevention campaigns doesn’t fix the fractured system she’s currently working with. While the money organizations spend on research is important and needed, her state needs help now. People aren’t being reached, and the system is too broken to save them.

“We approach everything with a shotgun,” Henfling said, describing mainstream suicide prevention advocacy today. “We shoot out these big wide blasts and we hope that some of it lands. Really what we should be focusing on are these targeted approaches.”

The Underserved

Most suicide prevention campaigns encourage people to get help when they’re struggling with suicidal thoughts — but if the help people seek is unavailable or unaffordable, awareness can only do so much.

For example, for Black people, access to mental health services can be a real concern. According to the American Psychological Association, African Americans are more likely to live in high poverty neighborhoods with limited to no access to mental health services.

Similarly, less than one in 11 Latinos with mental disorders contact mental health care specialists, and 36 percent of Hispanics with depression received care, versus 60 percent of whites.

Even when people of color do live in areas with decent access to mental health services, they may have a hard time finding a provider wh looks like them or shares their experiences. Also, discrimination can exist in a therapeutic setting. A 2016 study found that therapists are less likely to call back and offer an appointment to people who “sound like” they’re black or from a lower-income background.

Then, for those who do reach a point of being suicidal, because of how the mental health system is set up, the police may be called. While interacting with police can be a scary experience for anyone — especially when you’re feeling suicidal — it can come with more risks for people of color. In 2015 and 2016, one in four police shootings involved a person with a mental illness. In 2016, the victim was black in 24 percent of police shootings.

Police shootings, discrimination and racism are all real reasons people of color might struggle with their mental health — regardless of any diagnosed mental health condition. Jasmin Pierre, who founded The Safe Place, an app for the Black community to talk about mental health, said mainstream suicide prevention campaigns often fail to mention the specific issues that can affect Black Americans daily. “Racism, police brutality, colorism… all of that really affects our mental health,” she said.

Sara Williams, a Ph.D. Student whose research focuses on gender, sexual identities and suicide attempt survivors, echoed similar concerns for those in the LGBTQIA+ community. General suicide prevention, while important, she argued, doesn’t often cover what the LGBTQIA+ community needs, despite the fact that young people in the LGBTQA+ community are five times as likely to have attempted suicide compared to their heterosexual peers.

Mainstream suicide prevention efforts tend to neglect some of the very specific issues that contribute most significantly to increased rates of suicide among the LGBTQIA+ population, which range from social-environmental issues to physical health issues and limitations in access to care.

Factors like childhood trauma from bullying, mistreatment by family members and social isolation can all be factors that influence the suicide rate in the LGBTQIA+ community. Also, according to the National Alliance of Mental Illness, “Health care providers still do not always have up-to-date knowledge of the unique needs of the LGBTQ community or training on LGBT mental health issues.” Forty percent of transgender adults reported having made a suicide attempt — a rate 26 times higher than the general population — and access to health care of all kinds is still a major issue for the transgender community.

So when we tell these groups of people to “get help” — it might not be so simple.

Suicide is complex, and different communities — as well as different individuals — have different needs. Whether it be lack of access to care or the reality of discrimination, suicide prevention can’t ignore the context in which people live in. Pierre though, says she is often called “racist” when she talks about mental health from a black perspective, like she’s excluding white people by talking about what the black community specifically needs.

“We are forgotten about a lot,” she said. “Oftentimes, I feel no one cares about how everything that goes on in our environment really affects us.”

The Forgotten

Jenny Andrews — who also goes by Jenny Big Crow — lost her first friend to suicide when she was 13 and has since lost three more. She grew up on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. It’s not only the poorest county in the United States but has the lowest life expectancy as well.

According to statistics produced by the tribe, the teen suicide rate is 150 percent higher than other places in the United States. In general, Native Americans have the second highest rate — which is shocking when you consider they only make up about 2 percent of the total population.

Andrews is a suicide attempt survivor herself and says she feels ignored by mental health campaigns and suicide prevention efforts.

“People don’t even realize we’re here,” she said. “A lot of the issues going on with my people, you don’t hear about it. We don’t have a voice.”

Along with issues like poverty and rampant alcoholism (about 85 percent of families on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation are affected by alcoholism), Andrews says, historically, her people have been stripped of their identity. Her great-grandfather, only three generations away, was forced to attend government-run boarding schools so he could “assimilate” into American culture.

“We lost a whole generation of identity and our culture, and we were taught to look at it as bad,” she said. “Thankfully, we’re in a place where we’re trying to get our culture back. But even then, it’s such a struggle. You struggle with all the things that happened to our people.”

Culturally, Andrews explains, there’s a huge stigma surrounding mental illness and therapy. Because their community is less individualistic, “If one person goes to counseling or therapy, it looks bad on the whole family,” she said. Also, even if you do see a counselor within the tribe, confidentiality is a huge problem. People talk in such a tight-knit community, and she says younger people have expressed fear that if they talk to a counselor, the whole tribe will know what they talked about.

As far as what her tribe needs from the suicide prevention community, Andrews says first and foremost, she simply wants acknowledgment — both of what her people are going through and the mental health resources they lack. But, she also thinks awareness needs to be spread about how beautiful and vibrant her culture is. That it’s not all doom and gloom. That there is hope for tomorrow.

I feel like we’re a forgotten people… It would be a good idea to not just focus on the bad — but to highlight the beautiful parts of our culture as well. That would give teens and youth and people pride on who we are.

The Misunderstood

This summer, a study found that autistic adults who “camouflage,” or attempt to appear as neurotypical as possible, have a higher risk for suicide.

Although Joelle Marie Nourse was happy the study brought some attention to suicide in the autism community, the findings made her say, “Well, no shit.”

“A. Yeah, we want to kill ourselves. and B. It’s because you make us do things that go against ourselves,” she said. “You make our goal of our life to pretend to be like other people, and you literally punish us in every way possible if we don’t want to do that, or if we don’t aspire to be so.”

Nourse is autistic, bipolar and has obsessive-compulsive disorder. She says for most autistic people she knows, the suicidal thoughts started when they were young. Even if the language was vaguer (like, “I want to disappear”), autistic children sometimes learn from a young age they must change themselves to “fit in” with the world around them. Not only does this pressure start early, Nourse said, but it’s also nearly constant.

This is literally every minute of the day. Like this is supposed to be our goal. Walk normal, and talk normal, and make normal facial expressions… You don’t get a break unless you sit in the closet, but then that’s not normal. It’s really messed up. You just end up hating yourself.

Up to 50 percent of autistic adults have considered suicide, but how this suicidality is expressed may differ from “typical” suicide warning signs. Nourse said in her personal experience, autistic adults are less likely to inform others they need help because of how “black and white” and logical their thinking can be. It’s more likely for an autistic adult to make the decision to kill themselves once a “certain line” is crossed. Nourse explained:

I think for a lot of autistic people, it’s not, I’m going to inform people I need help, because of where my line is. I cannot get out of this pain. I have no other way to get out of it. It’s not like I want to die, but I have explored all other options… They’re not going to necessarily drop a lot of hints once they reach that point. They’re going to be like check, check check, OK now.

While some unfairly assume people on the autism spectrum are unfeeling and apathetic, this couldn’t be farther from the truth. Nourse said people who are autistic often have a rich, and even intense, internal world. Sometimes, though, autistics are taught how they cope with these emotions are unacceptable. Stimming, for example, is sometimes discouraged, even though that’s how many on the spectrum deal with feelings of frustration or overwhelm.

“We’re under such extreme pressure to seem ‘normal,’ but then when we use our coping skills, which are usually kinds of stimming and finding our own ways to socialize, we’re told that’s not OK either,” Nourse said. “It’s basically because it makes everyone else uncomfortable.”

There’s a lot of misunderstanding about what autism is and isn’t, and with the autism community’s complicated (and vastly, critical) relationship with big autism organizations like Autism Speaks (in 2016, the former director of public health at Autism Speaks joined AFSP as a senior director), Nourse says she understands why some in the suicide prevention community might be apprehensive to tackle suicide among autistic people.

What she personally wants is acknowledgment. Acknowledgment that suicide among autistics in a problem that needs to be addressed and acknowledgment that suicide prevention for autistic people isn’t just about crisis intervention but about how autistic people are treated their entire lives.

“It’s embracing people, it’s supporting people, it’s honoring people as who they are and not having them suppress who they are,” she said. “We need to embrace people and what they need to do for themselves. Stop telling people to deny themselves, because it’s killing them.”

Identity-Specific Resources for Suicide Prevention

This piece only scratches the surface. When it comes to preventing suicide, every individual has different needs, influenced by where they came from and who they are. When we spread information during National Suicide Prevention Month and beyond, we can’t forget to consider this context. We can’t tell people to get help without making sure help is available for them. We can’t tell people there is hope without making sure hope is tangible in the environments in which they live.

In some ways, suicide prevention is beautiful because of how universal the messages can be: We need you here. We want you to stay. You are worth it. When we combine these powerful messages with more specific ones — working with people in the communities who need it most — we’ll be able to reach more people and do more good.

If you’re looking for more information, here are some identity-specific resources to explore.

- Don’t Forget People With Disabilities When You Talk About Suicide Prevention

- Why We Need to Include Chronic Pain in Suicide Prevention

Men’s Mental Health

Minority Mental Health

- The Safe Place

- Therapy for Black Girls

- Healing Melanins

- People of Color & Mental Illness Photo Project

- National Asian American Pacific Islander Mental Health Association

- Native Communities of Care