10 Lessons From the Memoir of Marsha Linehan, the Creator of Dialectical Behavior Therapy

When I was in dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) for a year, we regularly watched Marsha Linehan — its creator — in her “Crisis to Survival” skills videos and the opinion of her was mixed. She was at times a polarizing figure. Perhaps this was an antipodean bias against her (perceived) grating Tulsan accent, or over-the-top manner. But for me, I loudly declared my love. I felt she was the ultimate wise mind

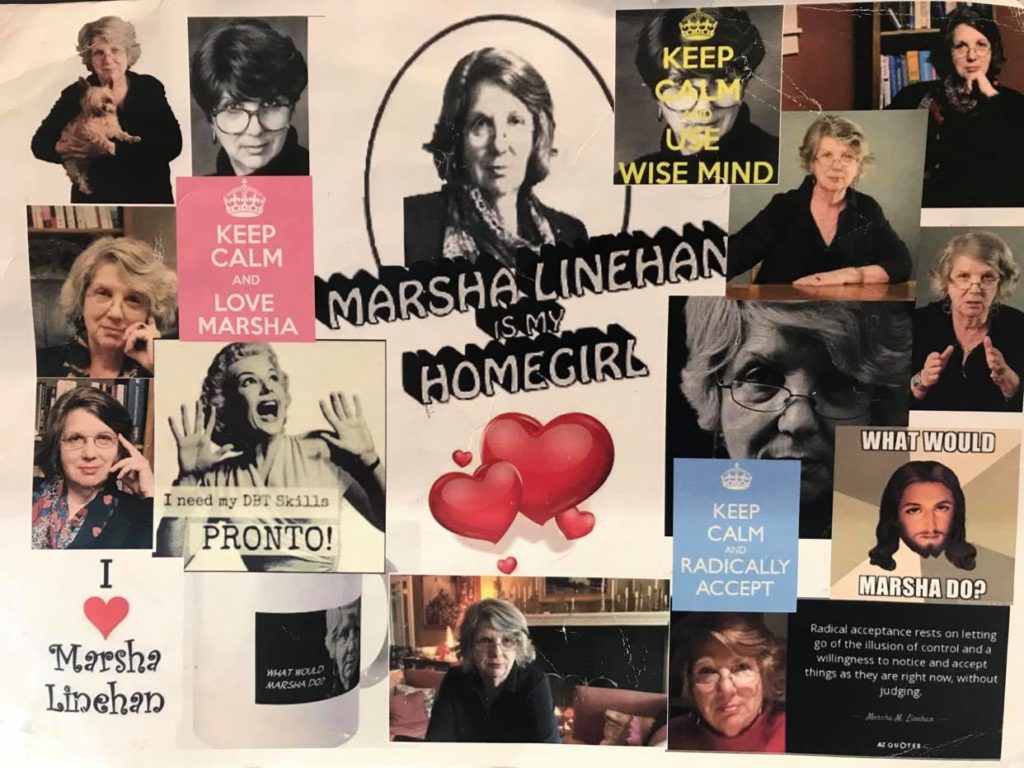

You see, early into the therapy, I had found out that Marsha herself had been in a psychiatric hospital in her late teens. Toward the end of her stay, she made a vow to get herself and then others out of hell. This impressed me so profoundly. My fellow DBT participants did start to wonder if mine was the borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptom of all-or-nothing idealization. One joked, in my birthday speech, that if Marsha popped the (marriage) question, I would consider going to the “dark side” — I’m gay. My beloved DBTers also made the Marsha posters for me, shared in this article.

And so, when I got hold of her memoir “Building a Life Worth Living” last week, I read it mindfully: with the same intensity of focus and attention to detail that I approached my DBT. I finished it in a few days and then quickly read it again. Like her therapy, her memoir is personal and pragmatic. It is easy to read with mostly short, simple scientific-like sentences — nothing to block the power of her life story. I was deeply moved and inspired. I already want to put Marsha’s life lessons into use and share, with you Mighty readers, 10 points that have stayed with me after reading. I am sure many of you have done, are doing or will do DBT. Of course, my 10 points are no substitute for reading the memoir yourselves. I hope I can inspire you to do so. Spoiler alerts do apply.

Here are my 10 takeaways.

1. Marsha is one of us.

When she was 18, she was admitted to the Institute of Living in Connecticut because of social isolation and depression which developed, once in the hospital, into full-blown self-harm and suicide attempts, to the point where she was secluded for months and considered one of the “worst, most disturbed and most untreatable” patients. She stayed there for two years and one month, and during that time she was given loads of drugs and a version of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

The scenes of seclusion, where she was once placed for three months, are upsetting because they just seem to reinforce her behavior rather than treat it. She describes it as being pursued relentlessly by a menacing person who would always catch her. Later, when she begins to develop a behavior therapy for highly suicidal patients, she attributes her skill as both a therapist and a researcher to being able to understand how her clients feel.

But does/did Marsha have borderline personality disorder?

Marsha addresses this question by saying although her memory is terrible as a result of the ECT and medication, her sister and a longtime friend strongly believe she did not exhibit BPD symptoms until the time she began her traumatic hospital stay. Marsha herself says this is correct — that she did meet about five criteria when in hospital — but that basically ends the discussion of her borderline diagnosis, apart from the fact that journalists now refer to her as having BPD after her “coming out.” (See point four.) It seems she doesn’t want to be defined by a diagnosis, and this becomes important when she later develops a behavior therapy. She does struggle for a while with self-harm and suicidal impulses, but after her 21st birthday, she has an experience of spiritual enlightenment. She repeatedly treats her symptoms with spiritual enlightenment, devotions, meditations and experience with God.

2. Marsha’s mother never really approved of her.

And her father also didn’t approve of her after the hospital stay. Marsha did not meet the accepted “thin and delicate” feminine look and subservient character for a girl of that time. She was irrevocably damaged by her invalidating mother. Her mother tried to mold her into an ideal of femininity she believed would allow her to have a successful life, but Marsha was the antithesis of this ideal. Throughout her life after the hospital, she struggled with the legacy of her mother’s invalidation, her condemning disapproval. This leaves her with searing pain.

3. Marsha’s vows to pull herself out of hell, and then help others get out of hell.

This is a vow she makes directly to God while sitting at a piano in the psychiatric hospital. It is indeed a higher calling. This calling saves her life and shapes the rest of her professional life. While in the hospital, the vow helps her to pull herself out of hell so as not to be sent indefinitely to a public hospital. Her vow then forces herself to work, move out of home away from her parents and Tulsa, to night school and finally into university. Crucially, her vow extends beyond herself which becomes the focus of the rest of her life. In fact, the groundbreaking behavior therapy she ends up developing is very much rooted in her spiritual experiences both as a Catholic, and later as a Buddhist Zen Master.

4. She did not disclose her story until late in life.

This is remarkable but not really surprising. I find it extraordinary that she was able to hide the scars on her arms. On the one hand, this shows a formidable strength of character — to hide her history from her colleagues when some would ask what happened, and from the many other academics who wanted DBT to fail. But this is also upsetting: why should she have had to cover up her medical history? When she was honest in her application for a graduate program when asked to explain her missing years after school, she was rejected from universities without really a plausible reason.

Still, I long for a world where someone who designs a new behavior therapy can be truthful about where their motivation came from. In the end, the story of her final “coming out” in front of many she loved and worked with — back at the Institute of Learning, where she had been in hospital 40 years earlier — is very, very powerful.

5. She fell down repeatedly but always got back up again.

This is really bracing but also sometimes hard to identify with. The amount of setbacks Marsha faces feel almost never-ending at various points in her story. Some of these setbacks I’ve already mentioned, both professional and personal, which also include three unsuccessful romantic relationships which devastated her for a time. Through most of them, Marsha would experience great distress, but she would always get back up again. Marsha attributes this to growing up with two brothers, who trained her for life’s bumps. She says, “I learned … that when I got knocked down by them, I should bounce right back up like a Bobo doll.” The origin came from the resilience of her vocational vow, which also required those she was attempting to get out of hell to persevere: “Never give up. It doesn’t matter how many times you fall; what’s important is that you always get up and try again.”

6. Marsha is honest about her flaws.

Maybe some of my DBT friends were right. Throughout her whole life, Marsha’s mouth is described pejoratively: her brothers called her “Million Ton Mouth Girl” and there are a number of occasions she describes her mouth turning people off. She was quick to give her opinion, unrelenting in her arguments and demand for evidence, couldn’t keep her judgments to herself and could even be socially insensitive, especially in her bent for behaviorism. It sounds like many of these things may not be so negatively regarded today, and surely also help explain how she achieved her great success. Lastly, the founder of DBT admits that it took her decades to learn to be politically savvy.

7. DBT was originally designed for suicidal people, not necessarily for people with borderline personality disorder.

I didn’t realize that BPD was not targeted at all. Marsha writes that she has never been interested in BPD as a disorder in itself and did not begin targeting this personality disorder. This is evidenced when a woman from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) committee, initially reviewing DBT, told Marsha she thought it was a treatment for BPD. At this point, Marsha admits she had barely heard of the disorder. Instead, she was interested in treating suicidal and self-harming behaviors, or other “out of control” behaviors: “I treat a set of behaviors that gets turned into a disorder by others.” This is ironic, given how DBT has become the dominant treatment for BPD, which the evidence shows to significantly work. It seems that just as Marsha doesn’t readily identify as a person with BPD, she admits her therapy wasn’t initially designed specifically for those living with BPD.

8. It is a behavior therapy, not a psychiatric or psychodynamic treatment, which has a unique, human touch.

DBT was developed to have a close, genuine and equal relationship between therapist and client, rather than focusing on “fragilizing” the pathology of the client. Marsha wrote the DBT manual in a “personal rather than academic voice,” removing any unhelpful medical jargon which is perhaps why most of those who use the manual refer to her as “Marsha.”

9. Acceptance/change is the original, core dialectic that DBT is founded on.

“At the core of DBT is the dynamic balance between opposing therapeutic goals: acceptance of oneself and one’s situation in life, on the one hand, and embracing change toward a better life, on the other.”

The dialectic is, therefore, the fundamental synthesis between the two. DBT asks you to accept, even radically accept, your situation including in the past, and then from that position move toward change. You cannot change your behavior before accepting the behavior isn’t working for you. And more fundamentally, DBT itself can’t work unless you accept it. You have to want to change.

I was aware of many dialectics when doing DBT, but I now realize this was the most important.

10. If I can do it, you can do it.

At the very beginning of the memoir, there is this standalone sentence on its own page. A mantra for us. This is what Marsha often says to her clients, and now I wonder how we can fulfill it.

What is it that Marsha did, that we can or even would want to do?

Definitely, clawing herself out of hell at a time when people, even her own family, had seemed to have given up on her. And turning that experience of hell into a vow to help the lowest of the lows. Yes, I can do that too. For example, when I was in hospital recently, I helped my friend out of hell on a night when he was acutely suicidal. Can we develop a revolutionary behavior therapy as Marsha did through scrutiny, criticism and rejection? I’m not sure. Perhaps there is only one Marsha! But even when people criticize us — even the DSM-5 devalues our professional achievements — it is rousing to have a fearless leader who scraped herself out from the bottom of the pit and profoundly transformed herself into a success. Crucially, she did that not because she stopped suffering, but rather she used the suffering to help her be successful. Here I really can take heed.

What I take from this is that Marsha is motivated by a higher calling and a love. This is so much more palatable to me than someone who does everything for their own glory.

I wish I had more of her professional tenacity. I wish I wasn’t so devastated by criticism. But Marsha says directly to that: keep going! Never give up!

And I really believe we too can help bring understanding and also help bring people out of hell.

Isn’t that what we are doing at The Mighty, after all?

Images via contributor