Why Is Accessing Mental Health Care Still So Hard for Someone Like Me?

Why does accessing mental health care still have to be a struggle for someone like me?

The other night I found myself jarred out of my sleep at 2 a.m. again crying and terrified from the nightmares. I quietly got in the shower and tried to wash everything away, trying to ground myself in the present, an automatic routine I’ve done for the past 20 years even before I knew what the words trauma and PTSD meant. As I get back in bed, I am angry and concerned that I haven’t had much luck locating mental health treatment resources as a biracial black transgender man with multiple disabilities including autism, chronic illness, complex PTSD and depression. I’ve been searching for months, especially as I have been struggling with major life transitions, stress, a racial pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic.

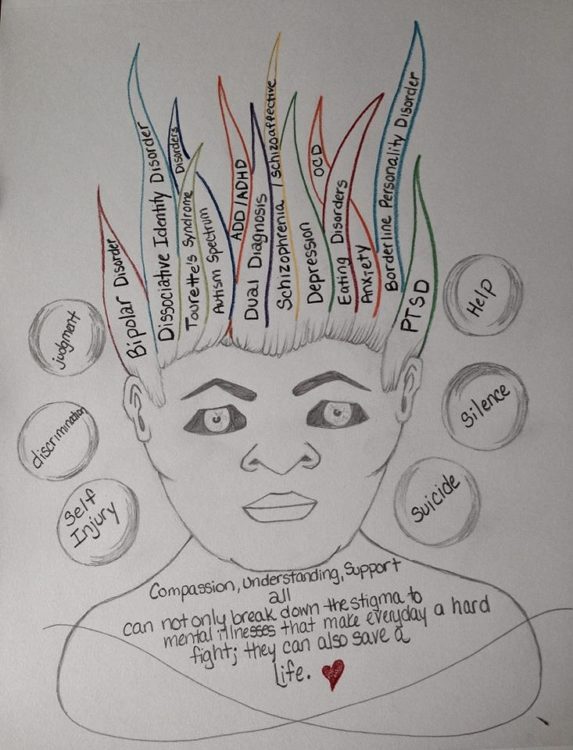

But trying to find a therapist who takes my insurance, is trauma-informed, has cultural proficiency training, is LGBTQIA+ friendly and has experience across different areas of my identity is challenging. The struggle to locate equitable and supportive mental health therapy and resources as a person who belongs to multiple marginalized groups leaves me often feeling like I was made wrong. This is especially when I am seeking help in a western society that is not equitable for minorities and mental health resources are interlaced in ableism, a lack of cultural proficiency and a lack of a holistic whole-person approach. Wow, even now thinking about this, the words of diagnosis and knowing what support I am looking for mixed with how far I have come in advocating for myself reminds me of how in many ways navigating accessing quality mental health care and resources is just as hard as it was 17 years ago when I was thrown into the system without any awareness or understanding of what any of it, including mental health, even was.

Each day in the background, I am thankful I made it here to another moment.

Each day in the background, I also wonder if coming of age in the mental health system contributed to the progression in my neurodegenerative disease and recent diagnosis of young-onset dementia. I have worked on lessening how hard I am on myself and acknowledging that even when I was coming of age, I was still fighting for my health and my life — just in a system that unfortunately did more harm to me than good. Even from that first terrifying encounter 17 years ago, my freshman year of college away from home when I was having my dorm room broke down by the police, handcuffed, put in a cop car and dropped off in the emergency room, handcuffed to a bed being rolled down to the adult psychiatric unit three months after my 18th birthday with no identification, separated from my family and committed to the psychiatric unit for the next week that set the path for what would come next.

The roller coaster ride of a different kind began. A roller coaster that would take me 14 years to get off and still leaves me fighting the impact today. I traded in my hopes and dreams for weekly doctor appointments, therapy appointments, group therapy appointments, support groups, cycling through different combinations of antidepressants, antianxiety, mood-stabilizing and antipsychotics medications that when counted in my file added up to 38 psychotropic medications in a span of seven years. The physical and cognitive impact related to side effects and adverse interactions with my neurodegenerative disease were endless, requiring more therapies, doctors, medications and assistance with swallowing, speech and using mobility assistance devices. I felt like I wasn’t getting an equitable chance at life or treatment as the roller coaster ride just kept revolving nor did anyone, including me, seem to have the awareness or knowledge of how my autism and my other disabilities, the different parts of who I am that are marginalized, and my trauma and sexual assaults played a roll in how I struggling to access the right supports in the mental health system and was declining instead of healing and thriving. The whole process left me feeling increasingly like I wasn’t made in a way that could be helped, that I was a mistake and that I would never find a way to get better.

It wasn’t until the fall of 2016 when I was given a resource for a trauma-informed outpatient therapist who was LGBTQIA+ affirming and also had experience with individuals living with autism and other disabilities that I was able to get off the roller coaster and begin a different path more aligned with holistic health, transformation and connection to my authentic self. I started gaining a better understanding of who I was as a person and how my differing abilities and my past trauma impacted my overall interactions, health and living. I also began to see how this interacted with other parts of who I am as a person, and how these parts made up the whole of who I am engaging with the world around me and trying to access support. Over time I not only discovered what self-advocacy was but also became my best advocate.

In becoming my own best advocate, I discovered ableism and intersectionality were things I have always navigated in different ways on a daily basis including in different spaces, school, predominately White communities, with mental health resources and health care access. I reflected on my experience having a SAFE exam and rape kit done while being interrogated by three police officers for three hours at the hospital, who asked me to educate them on how my disabilities impacted my ability to fight back against my assailant by repeatedly demonstrating while verbally explaining. I have just scratched the surface of the layers of navigating ableism and intersectionality within an ableist society within the mix of racism, sexism, transphobia and homophobia, and more that is also deeply embedded in the institutions and branches of systems that serve the society I live in, including the mental health system.

I have seen growth in areas such as income-based resources, cultural proficiency training, trauma-informed training for health practitioners and the importance of creating an affirming environment. However, I also know there is still a long way to go to make mental health care more equitable and accessible for minorities, especially minorities who belong to more than one marginalized community like me. The first step in addressing and removing the barriers that exist in accessing quality mental health care related to ableism, intersectionality and accessibility for minorities and marginalized communities is to acknowledge these barriers exist in the first place. It can’t be addressed until we see it as an issue that needs to be addressed, both within our own communities and larger communities and institutions we exist, interact, work, live and receive services in.