You Might Experience This Anxiety Response as COVID-19 Lockdown Ends

Reopening opens up all-new challenges to our mental health and brings a new set of fears.

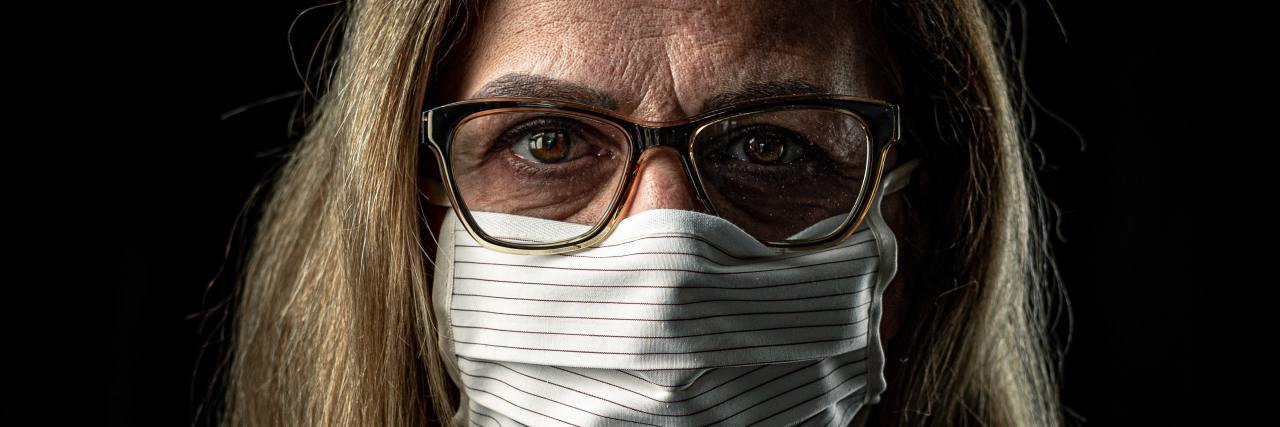

After a nice day at the beach where our social distancing was in place and the risk of contracting the coronavirus (COVID-19) was minimized with all sorts of precautions, a couple of friends and I decided to stop for a drink before heading back home. We found a nice open-air bar at the shore where they had a booth for drinks and another for food, and where the tables were dispersed around the sundeck with enough distance between them. We arrived wearing our masks, and as soon as we entered the bar, most eyes were on our faces. Everyone stared at us as if we were naked at a family reunion, or better yet, as if we were the only ones dressed at a nude beach. We were indeed the only ones wearing a mask and we felt the disapproval of everyone around. The way they stared at us seemed to have the intention of making us feel guilty, as if we were doing something wrong. It was a difficult moment. I watched my friends debate between removing their masks, leaving, or staying with their masks on. We decided to stay, without masks, reasoning that we were respecting social distancing and that the bar was totally open air.

One of my friends was visibly upset. She started ruminating about everyone else’s lack of social consciousness, the preposterousness of judging us for doing the right thing in the middle of the pandemic, the need to let them know the risks they were taking and the risk they were creating to others, and yada yada. From being simply indecisive, she went all the way to becoming a vigilante, and the tension in her body and her thoughts projected a clear image of tension and rigidity. I’m using the word “rigidity” not to critique my friend’s personality, but to point out the neurological phenomena that occurred to her in that instance. When we are presented with a situation where it’s difficult to make a decision about maintaining a sense of safety, our brain may activate two different defense mechanisms at the same time:

1. It would get ready to start a fight/flight response to contest the danger, which in this case is to prevent the contagion from others.

2. It will also try to adjust to being calm, which in this case was to stay for the drink but without the conviction to stay, and submitting instead.

That state is called “freeze.”

Freeze Equals Move/Don’t Move

That type of activation, “freeze,” according to Kozlowska, et al, (2015), is a flight-or-fight response put on hold; she explains it as putting a brake on the activation of the basic motor patterns or flight or fight, like ones you’ve probably heard of: attack, running, treading. This “brake” process prevents the expression of the active defense while it activates the slowing down of certain functions imposing immobility, canceling any movement and forcing the system to stay put.

The result is a mind-body state characterized by a narrow focus of attention; the individual is focused on the threat and is ready to respond, though not yet, which creates a state of rigidity both mentally and physically. In my friend, it manifested as anger against the people who were not wearing masks combined with the frustration to stay, with tension from the inability to adapt and the need to check for danger.

An Exhausting Defense

Having to stay in a state of indecisiveness or forced compliance means that the autonomic nervous system will keep its two branches activated in unison, similar to pushing the gas pedal and the brake in a car at the same time. Imagine if you did that — the car would continue consuming gas without moving an inch.

In your body, that means that a person will be consuming double the amount of energy than in regular circumstances. It also means that the person will be confused about what’s happening internally. The person may feel powerless even when they’re putting so much energy in defending themselves, feeling angry at the danger but also at themselves for not acting on the feelings of fear.

My friend was in pain; she couldn’t understand why we didn’t see her point, and was shocked by the fact that we were still there, participating in one of those moments that have been portrayed several times in the media as reproachable for not doing our part in stopping the pandemic. She wanted to believe that we were reintegrating to “normalcy” by accepting spending the day at the beach, while her system was still believing she was in danger, and felt as if she couldn’t decide — or maybe we didn’t let her decide — whether it was best to stay or to go, confronting a situation where she may have felt that she didn’t have a choice but to wait for us to finish our drinks.

Overwhelming Mixed Signals

One of the main problems we are living through is the confusing information that the media distributes. And not only the media whose job is to inform, but the media that creates content as a way to express opinions or to participate in society with partial points of view and lack of accurate information. It’s almost impossible to know at this point what’s true and what’s not, let alone feel anything close to certainty. We don’t even know what type of virus or illness we are afraid of contracting. There are constantly conflicting reports about whether the mask protects us or others; if young people have a lower risk of getting sick or not; if our pets will get it; if going to bars and hanging with friends could kill us. We don’t know if bars or theaters or the world we knew will cease to exist.

We only know that this has been going on for almost four months and instead of getting better, they say it’s getting worse. We also know it has ruined our social, financial and physical lives. We don’t know who to blame, how to protect ourselves, what to protect from, or why in heaven this is happening to us. We feel confused, lonely, angry, worse off than before and in danger. We want to go back to “normal” and believe that the risk is gone; it doesn’t seem to be the case, and we don’t know if it will.

Our brain can’t digest so much uncertainty; it gets overwhelmed and will try to take us out of that state by removing the control from our will. The brain, doing its thing — as in making us anxious, depressed or rigid — is supposed to be keeping us protected from danger; it doesn’t matter at what social or psychological cost. That’s what is called “defense.”

Freeze as a Defense

I’m using the word “defense” not as a conscious decision or as a personality trait, but as a primitive mechanism wired in our brain to protect us from predators and death. To freeze is actually a healthy defense designed to prevent the fight/flight form getting fully activated; when fight/flight does, it creates a series of changes that are taxing to the body and could create more permanent damage. Staying in freeze mode is a way to give the space to the executive part of the brain to make a more objective evaluation of the threat controlling fear. Some scholars (Bastos, et al, 2016; Volchan et al, 2017) have described it as “attentive immobility” which could be seen as the preparation to flee when escape is available and immobility when escape is blocked.

Being at the bar under this type of defense made my friend stay in a more vigilant state as a way to feel safer. Staying put avoided letting her forget the risk; if she hadn’t, and instead relaxed, she maybe could’ve come too close to the people around her who weren’t wearing masks and could have been centers of infection. It also kept her ready to get out as soon as we finished our drinks. Staying in a mode where you keep assessing risk during the remainder of this pandemic is not a bad idea if you venture out and start incorporating into the world again.

Rigidity as a “Defense”

A possible solution to dealing with the unpredictable level of risk is to become determined to avoid yielding toward another person’s viewpoint; by doing so, becoming fixed in a particular belief you see as the safest, and dismissing all others, is a tactic that could seem helpful. That could appear to be a safe bet while information becomes more reliable.

The trick of that way of defense is that it works by design to motivate the person to continue reading every single piece of news and articles looking to either confirm the validity of that way of thinking, or to find the piece of information that will release them from that exhausting state of fear.

Not staying in a state of hypervigilance could feel anxiety-provoking, even when being hypervigilant is an anxiety state; one of those ironies of our nervous system. Not staying alert could also mean that the person has given up hope, and therefore stops “pushing the gas pedal.” The constant use of the defense: accelerate, brake, accelerate, brake, without moving, harms more than it helps. Keep in mind that this type of “rigidness” as a good thing — because it is a defense — should be a temporary state; keeping the defense for too long develops rigidity as a new habit for the brain to operate and it could become an ingrained trait.

Thawing the Defenses

Even when freeze can be helpful, living with the defense mechanisms active is not the best way to protect yourself. Defenses are automatic and assume a much greater risk than what your cognitive brain can perceive. Fear, even when it’s protecting you, it is still fear, and fear is illogical. Once fear fully takes over, it will make you feel more defenseless than protected.

We still have a long way to go before we can recover our mobility and “normal” routines. One of the best solutions for when we feel “forced” to have both pedals pushed — gas and brake — is to decide if we want to stay in the same place, or if we prefer to move. Making a decision is the best defense:

- If you decide to continue with the brake on, as in keeping yourself in quarantine to minimize all risks, you could stop pushing the accelerator; there is no need to try to move yourself in a direction of normalcy that makes you feel unsafe.

- If what you have decided is to move on to recovering your lifestyle, there is no need to continue braking; you understand the risks and assume the consequences.

In the case of my friend, she could have decided to relax and chill, or she could have yelled at us and demanded to get out of the bar. In either scenario, she would have been making a decision that would have helped her stop living driven by fear.

Struggling with anxiety due to COVID-19? Check out the following articles from our community:

- An Activist-Therapist’s 15 Affirmations for Hope Amidst COVID-19

- Hey You: It’s OK to Grieve the ‘Small’ Things You’ve Lost During the COVID-19 Outbreak

- How Can You Tell the Difference Between Anxiety and COVID-19 Symptoms?

- 7 Things to Do If Social Distancing Is Triggering Your Depression

- 10 COVID-19 Emotions You’re Not the Only One Having

- What It’s Like to Be a ‘Highly Sensitive Person’ in the Time of COVID-19

Photo by Peri Stojnic on Unsplash