Biology Homework Assignment Asks Students to 'Solve' a Rape

Editor's Note

If you’ve experienced sexual abuse or assault, the following post could be potentially triggering. You can contact The National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 1-800-656-4673.

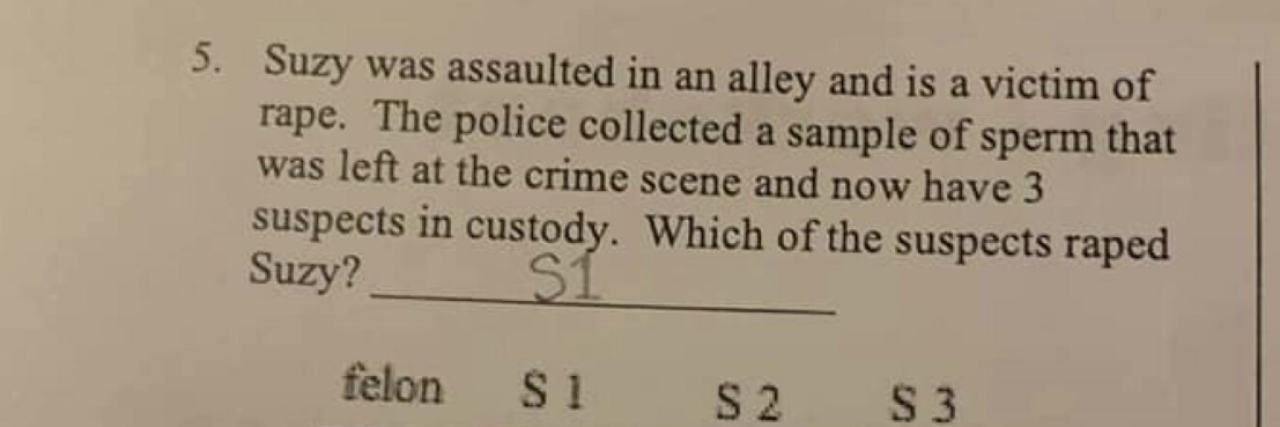

A story about a very unusual homework assignment given to high school freshmen near Houston, TX made national news on January 13. Students were asked to “solve a rape” by analyzing the DNA of suspects in question:

“Suzy was assaulted in an alley and is a victim of rape. The police collected a sample of sperm that was left at the crime scene and now have 3 suspects in custody. Which of the suspects raped Suzy?”

Question about rape ends up on biology homework assignment for 9th-graders at Klein Collins HS https://t.co/FVaSo0JXis pic.twitter.com/eNdf8oJ8QU

— KPRC 2 Houston (@KPRC2) January 14, 2020

According to local reports, when a few students spoke up about the assignment, parents were outraged and the school in question, Klein Collins High School, reportedly took corrective action against the teacher. “The assignment is not part of the District’s approved curriculum and is by no means representative of the District’s instructional philosophy,” the district said in a statement.

As a survivor of sexual abuse and advocate for survivors of sexual assault, I am extremely disappointed that despite the #MeToo movement and increased public discourse about sexual assault, we still haven’t come very far in how we discuss this subject, particularly with our youth.

Instead of actually teaching students about sexual violence, this question reduces a complicated and horrendous crime to a seemingly innocuous science experiment.

For many students, rape and sexual assault are not faraway, hypothetical situations. According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), 1 in 9 girls and 1 in 53 boys under the age of 18 will experience sexual abuse or assault at the hands of an adult.

CDC data from 2017 shows, 7.4% of high school students have been “physically forced to have sexual intercourse when they did not want.” To put those numbers in context, in a school of 500 students, based on those statistics 37 teens will be raped.

Of the students who’ve dated, 6.9% experienced sexual dating violence, meaning they were forced or pressured into partaking in a sexual activity they weren’t comfortable with.

And sexual assault isn’t just happening to high schoolers outside of school. Although schools currently have no national requirement to track or disclose instances of sexual violence, The Associated Press reported 17,000 official reports of sex assaults by students in schools from fall 2011 to spring 2015. While most peer-on-peer sexual assault occurs in the home, school is the second most frequent place it occurs.

Thanks to Erin’s Law, 37 states require public schools to teach a prevention-oriented child sexual abuse program. However, parents may opt-out if they don’t want their children to participate. While this is progress, especially for victims of sexual abuse, only 24 states and the District of Columbia mandate sex education. Out of those states, only eight states require mention of consent or sexual assault.

Ironically, Texas isn’t on that list — so it’s possible students who were exposed to that rape-themed biology homework question had not received any formal education or guidance about rape and sexual assault. Education about sexual abuse and assault must start in the home and in our schools at an early age for it to have any kind of meaningful impact on how society at large handles the issue. Without a solid foundation in both body safety, autonomy and age-appropriate sex education, our youth are at risk of not only becoming victims but perpetrators of sexually fueled crimes. We can do better.

Besides the basics of teaching about consent and sexual assault, schools don’t have a great track record for how they handle real cases. For example, just a few months ago, a 9-year-old girl in Maryland was told by a teacher to just “stay away” from the boys who threatened her with rape and simulated sexual acts over her clothes. If this is the response students get when they speak up (think: “Boys will be boys.”), it’s not surprising so few victims of sexual violence speak out about their assaults. Not only is our judicial system grossly ineffective at prosecuting sexual offenders, but victims are also often dismissed and blamed for the assault.

What can we do to combat this issue? End the stigma of talking about it. Parents, I’m talking to you. I understand that it may feel uncomfortable to bring this subject up with children. But can you afford not to? Children can tolerate discussing this subject, but the long-term effects of sexual violence on victims can be life-altering, including addiction, self-harm, PTSD, depression and suicide. We must do what we can to eliminate this epidemic.

Regardless of your political, religious, cultural, ethnic or socio-economic persuasions, there are many resources available to help teach these topics in age-appropriate manners within frameworks that can be adapted to your sensibilities. For younger children, it’s imperative that we discuss things like the anatomically correct names for genitalia, private parts, good touch vs. bad touch and “safe people,” the adults a child can trust to tell if they are violated in any way. Early intervention is key to long-term healing and prevention of victims becoming abusers themselves.

For older children, sexual education is critical. Whether we’d like to believe it or not, teens are having sex. Kids need to know what the long-term effects of that kind of exposure mean for the future. They need to be taught consent. Boys, in particular, need to develop healthy concepts of what intimacy between two people really means so that they don’t think that sex is supposed to be violent or disrespectful of women. And, I’d like to note here that sexual violence can be perpetrated by women as well and that men can also be victims. Let us not silence boys by perpetuating stereotypes of toxic masculinity.

Sexual violence is everyone’s problem. The only way to eradicate it is to take it seriously and to start talking. Stand up for victims, don’t denigrate them. Hold perpetrators accountable for their actions. And above all, don’t allow others to disregard or minimize the issue of sexual assault the way this biology teacher did.

You can watch Monika telling her story here: