What 'Tiny Pretty Things' Got Right About Trauma — From an Ex-Ballerina

Ballet… it’s one of the most magical art forms. Ethereal figures gliding across the stage, light as feathers, transporting us to different worlds through grande jetes and pirouettes. It all looks so beautiful that it’s easy to forget that under all the costumes and make up are young men and women who have literally sacrificed everything for the opportunity to be on that stage.

The show “Tiny Pretty Things” on Netflix offers a glimpse into this more sinister side of the ballet world. A psychological thriller soap opera, the show centers around the attempted murder of one of the most promising ballerinas at a prestigious ballet school in Chicago. While the plot of the show melodramatically depicts the chaos that ensues amongst the dancers and staff in the aftermath of the tragedy, the show itself does actually shine a light on the dark side of the world of ballet.

As a former aspiring ballerina, I found myself triggered by many of the themes explored throughout the series, flooded with memories of how the underbelly of this 400-year-old art form is fundamentally patriarchal, abusive and maintained through the strict manipulation of human beings into tolerating regular maltreatment. Here are some of those themes:

Dancing Through Injury

“No pain no gain” is a mantra that every dancer knows all too well. Not just normal muscle soreness from hard work, but dancing through injury. I can’t tell you how many sprained ankles and torn muscles I danced through. Pain medication, Salon Pas patches, liquid bandage and any other kind of pain management was a regular part of my routine. My feet were almost always raw and bleeding from rubbing against my pointe shoes. At one point my heels were so bad that even with bandages on, by the end of the show my pointe shoes were completely soaked through with blood. And the thing that’s most disturbing about it is that I had learned to just ignore the pain. Pain tolerance becomes almost a badge of honor, proof that you have what it takes to excel. One particular injury on the show really hit home. Bette, one of the nepotistic protégées of the group, endures a metatarsal fracture in her foot. She refuses to quit dancing even though the pain is intolerable. I had that exact same metatarsal fracture on my left foot in college while dancing the lead in a modern dance piece. We rehearsed for so many hours a day that I could barely walk, but I wasn’t about to give up the part. I sucked it up and did the show. To this day my left foot still feels slightly off from all the scar tissue left behind.

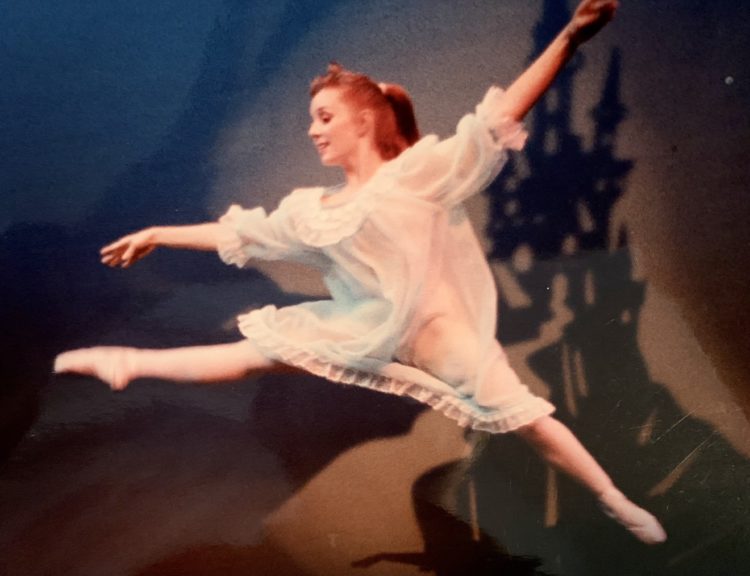

The author, from her dance days

Eating Disorders

Even if not all dancers develop full-blown eating disorders, many develop disordered eating habits and a deep sense of hyper vigilance regarding their weight. In the show the dancers are regularly weighed, comments are made by teachers and choreographers about them being fat, the girls talk about having to watch what they eat to stay thin, we see one of the male dancers regularly purge and in one scene, Bette stares at a plate of pasta like it’s the Devil incarnate.

Being a naturally short, large busted, big boned Eastern European girl, I always struggled with my weight. No matter how thin I was, I never was thin enough. My ballet teacher would comment almost daily on my weight in front of the class, made ultimatums about losing “X” amount of pounds for a part, would pinch my back fat and would constantly attempt to reign in my apparently distracting breasts. At one point I was playing Alice in a ballet version of “Alice in Wonderland” and in order to make me look more “childlike” I had two ACE bandages wrapped around my breasts to flatten them. I could hardly breathe but that was the only way I could do the part.

In college my ballet teacher actually poked me in the stomach and called me the Pillsbury Dough Girl on the very first day of my very first class my freshman year. When I worked at Disneyland they continuously tried me on in the Ariel wig because my coloring was perfect for the Little Mermaid, but I repeatedly got told I couldn’t do the part because once they fit me in the signature seashell bra I “looked like Dolly Parton Ariel.” My body was always wrong. Every audition I went to for summer programs I’d get accepted by companies like the Joffrey, Boston Ballet and Pennsylvania Ballet, acknowledging my talent and technical prowess but always putting in fine print “contingent on losing 10 pounds by the time she arrives.” Make no mistake, I was already restricting calories, taking laxatives and diuretics and exercising copiously to just be as thin as I was. It felt like a futile effort. I could never be what they wanted, no matter how disciplined I was or how hard I worked. It was devastating and it eventually developed into persistent body dysmorphia focused most pervasively on my bust. It’s soul crushing, self-worth destroying and one of the most dehumanizing aspects of being a dancer.

Toxic Environments: Normalizing Physical and Emotional Abuse

The old adage of “negative attention is better than no attention” is a way of life for many dancers. The head ballet instructor in the show is prone to fits of anger and regularly shames students during class, the main choreographer actually gropes the female dancers to elicit the emotional response he is looking for, and at the extreme end of this, the head ballet mistress knowingly has traded underage dancers to entertain men at an elite lounge where they are regularly being sexually assaulted for donations to the school. Again, not all schools or teachers behave like this, but I’ve seen my fair share of dubious behavior verging on abuse. It wasn’t uncommon for me to go home from rehearsals in tears because of something my teacher said to me.

I never said anything or would allow anyone to do so because I didn’t want to jeopardize my future in the company. I was a scholarship student and I couldn’t afford to do anything to lose that scholarship. Ballet is a classist elitist art form that generally is made unavailable to those in lower socio economic strata because the shoes, costumes and classes are so cost prohibitive. I came from a poor single parent family so I was one of the lucky ones. You learn to be OK with having your knees whacked with a stick or your body wrangled into positions that push the limits of your physiological capacity. You become desensitized to being screamed at, called lazy or called names because it’s all just part of the game. On the one hand dance teaches you the value of hard work and discipline, but it also fosters the normalization of abusive behavior which can bleed into every aspect of ones life, even years after you are no longer in the studio.

So why on earth would anyone want to be a dancer? Because there is nothing quite as exhilarating as being able to fly through the air like a bird, land gently like a cat, twirl like a top and have the ability to convey powerful feelings, stories and music through every pore of your body. It’s intoxicating. I loved dancing more than almost anything. And let’s be honest, getting the positive attention from an audience is incredibly seductive. Even those of us who didn’t “make it” look back at our dancing days with a sense of nostalgia and melancholy. I may not be able to do the things I used to physically, but the memories of the choreography and how my body felt doing it will forever be imprinted upon me. I have no regrets, just hopes that the ballet world can evolve to be more inclusive, less elitist, less patriarchal, less fat phobic and ultimately more humane. There’s a world of talent out there yet to be discovered that deserves a chance to be nurtured in a positive empowering way. I appreciate shows like “Tiny Pretty Things” that bring attention to these issues.