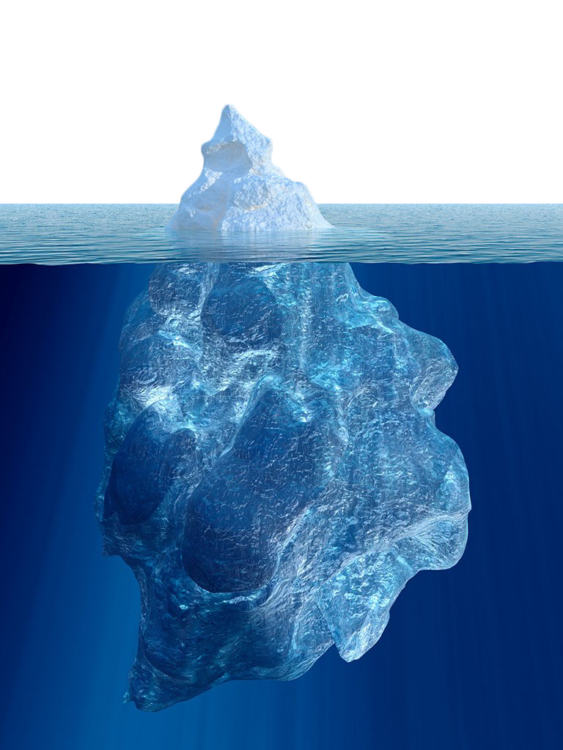

As someone who has been diagnosed with a rare, autoimmune, progressive and chronic liver disease called primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), it is incredibly important to me to participate in clinical trials whenever possible. Without participation from the rare disease patient population, we can never hope to achieve effective treatment or possibly even a cure for our disease. In my case, having PBC is a double-edged sword. PBC destroys the small bile ducts within the liver over time, leading to scaring (cirrhosis) and eventually end state liver disease (ESLD, also known as liver failure) in some, requiring a transplant. It’s an autoimmune disease, but biologics that work for ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s don’t effect PBC or stop the damage being caused. Rare diseases are often like icebergs — what you can’t see can indeed hurt you.

Clinical trials start with very complicated ideas and simple organisms until they reach a level where they can be used in humans. A researcher at UC Davis in California developed a way to cause a disease, which is essentially the same as human PBC in mice. It’s known as a mouse model. That mouse model is now a key instrument in ongoing research efforts around the world. This same researcher is the first one I came in contact with when I first was diagnosed. He held an informational meeting and requested blood samples from attendees if they were willing. I signed the consent form and gladly donated the blood for his research.

I had entered the world of clinical trials and studies. Clinical trials involve the use of some type of device or medication to treat a patient. Clinical studies are typically observational in nature and don’t require taking medication under development but may include blood, urine or saliva samples, non-evasive testing or other procedures or examinations.

A commercial for UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital that resonated with me, used the ad line: “Amid a thousand maybes and a million nos, we believe in the profound and unstoppable power of yes.”

This is the core of clinical research. Many ideas never get off paper to actual testing. Those that do are heavily regulated for safety and efficacy, patients are closely monitored throughout the trial and in the most common scenario, are assigned in a “double-blind, placebo controlled trial.” Neither the doctor nor you will know if you are given the actual medication or a placebo until after the trial is over. This ensures there is no bias for or against the treatment, often known as the “placebo effect.”

If a clinical trial makes it past the first couple of stages and into a stage 2B trial level, a small population of patients are recruited to take the medication under development for a period of time, typically 12-16 weeks, but sometimes up to a year. These results are then carefully analyzed to determine benefits to the patients, safety and meeting the goals of the trial. From there, larger and longer studies are conducted, some lasting many years (5-10 years) to ensure there are no long-term surprises that were not seen in the shorter trials. This entire process is overseen by FDA.

An example of why this process is so necessary is the drug fenfluramine/phentermine (commonly known as Fen-Phen). It was an anti-obesity (diet) drug that seemed to work very well in many people. Unfortunately, fenfluramine was later found to cause valvular heart disease and pulmonary hypertension in significant numbers, so the FDA requested that Fen-Phen be pulled from the global market. Had long-term studies and post-marketing reporting not been in place, patients using this diet drug could sustain significant injury to their heart or lungs.

Long-term clinical trials cost a pharmaceutical company millions of dollars, and when you are talking about a rare disease where less than 50,000 patients exist in the country, or an “ultra-rare” disease where they may be less than a dozen patients world-wide, you can quickly see the relevance of clinical trials and capturing actual patient experiences during development. Yet, if those dozen patients don’t participate in clinical trials for treatments, they will never have hope for effective management of their disease.

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), 95 percent of rare diseases have no approved treatment. The National Institutes for Health (NIH) lists over 7,000 rare diseases, the majority of which are pediatric diseases and >70 percent are genetic. Many of these are life-altering or life-threatening diseases, including my own, PBC. Due to the progression of my PBC, I now have cirrhosis (no, cirrhosis is not only caused by excess alcohol consumption) and quite possibly face the prospect of needing a liver transplant to live within the next couple of years.

This is why I participate in clinical trials. It’s not likely that it will stop my disease from progressing, or even causing my death. I participate because I have lost too many friends to disease processes such as cancer, liver, lung, kidney and heart disease. Without understanding how a medication treats a disease, what the risks are versus the benefits and what a treatment level and length is required, we could not bring new medications to the public to save lives, and improve the quality of life for so many.

I am enrolled in a clinical trial now that is an open label, phase 3 trial, after having previously participated in the phase 2 trial. This particular clinical trial is a minimum of four years long. I received the placebo the first time around, now I am taking the actual medication. I have participated in a half-dozen trials and another seven studies. It gives me a sense of purpose to help the bright minds working on effective and safe treatments. It takes time and a commitment, both of which I have. For all the others alongside who are also in clinical trails, my appreciation is boundless. You are simply the best. Some enroll because it is the only option for life-saving treatment, even though the chances are very low at success. Others, like me, know it won’t change my life, but it could dramatically change someone else’s. It’s a rewarding way to help my fellow PBC patient community members, and potentially others.

Being a clinical trial volunteer participant is not for everyone. But for those who can, I personally recommend you explore the options and see if you can participate. We need as many of us as we can get to be able to drive research, treatments and hopefully someday cures forward.

Getty image by Vladimir Borovic