What Is Self-Harm?

Editor's Note

The Mighty’s Condition Guides combine the expertise of both the medical and patient community to help you and your loved ones on your health journeys. For the self-harm recovery guide, we interviewed four mental health experts, read numerous studies and surveyed 2,500 people with a history of self-harm. The guides are living documents and will be updated with new information as it becomes available.

What Is Self-Harm Recovery?

Regardless of what you might hear, self-harm recovery is possible. By understanding the reasons you self-harm, learning new and safer coping skills to manage intense emotions, and seeking support from a qualified mental health professional, you won’t need self-harm any more.

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: For Young People | For Adults | For Parents and Loved Ones | Resources

Medically reviewed by the Child Mind Institute

Who Self-Harms? | Reasons You May Self-Harm | Self-Harm and Its Addictive Nature | Myths About Self-Harm

Self-harm is best defined as causing intentional damage to your body tissue without intending to die by suicide. Self-injury serves as a coping skill to get immediate relief from uncomfortable feelings, whether that’s feeling too much, too little or feeling overstimulated by a difficult situation and not knowing what to do.1, 15 Though many who self-injure live with a mental illness, not everyone who self-harms has a mental health diagnosis.

What Are Forms of Self-Harm?

- Self-harm or non-suicidal self-injury is officially defined as causing intentional damage to tissue on your body

- There are other forms of self-injury. When other types of behavior are harmful, they can fall in a broader category of self-harm

- If you think you’re self-harming, reach out for support from a trusted loved on or therapist for more information

For a long time, the definition of self-harm has been subjective. In the early days, tattoos and piercings were sometimes considered forms of self-injury. With more research, however, the definition of self-harm has changed. A working definition is now listed in the latest edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM 5), which mental health professionals use to diagnose mental illness.

According to the DSM 5, self-harm — or non-suicidal self-injury as it’s referred to by doctors and researchers — is causing intentional damage or injury to body tissue like the skin. Self-harm in this content does not include trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder) or excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Both of these specific types of self-harm already have a distinct label in the DSM under the obsessive-compulsive category. Ingesting harmful things is also considered a separate category of harming behavior.

Is an Eating Disorder Self-Harm?

Eating disorders are also not considered self-harm, though there can be crossover between self-harm and disordered eating. The same goes for substance abuse. Drugs and alcohol can cause damage to your body over time, but they are not considered self-harm without the intent to do immediate damage to body tissue. Similarly, tattoos and piercings aren’t considered self-harm unless the main intent is to damage body tissue.

If you currently self-harm, you may not see a reason why you should stop, especially if self-harm brings you relief that’s hard to find elsewhere. Though you may not see it as causing harm in the long run, self-injury is not a long-term solution for complicated emotions that will likely follow you throughout life.

You deserve love and support, and treating yourself kindly sets a positive example that you can and will get through emotional hurdles. It’s important to reach out for support, whether that’s a licensed mental health professional, someone you trust or finding strength from within on a good mental health day to outline a plan with coping mechanisms for when things get tough.

Who Self-Harms?

There’s no one answer to who self-harms because people of all ages, genders, races, sexual orientations and socioeconomic status may self-injure. Here’s what we do know:

- Some studies show that an almost equal number of male- and female-identified people self-harm, while others suggest the ratio may be closer to three females for every one male.1, 3, 4

- In general, research has shown that individuals who identify as female begin to self-harm at a younger age, engage in the behavior longer and use more dangerous forms of self-harm

- Those who identify as male are more likely to self-injure while under the influence of a substance or in social situations.3

- People who identify as LGBTQ are especially at risk for self-injury. An estimated 47% of females who identify as bisexual self-harm4

How Many People Self-Harm?

Self-harm may be underreported because there is still a lot of stigma and misunderstanding among the general public and even medical and mental health professionals. However, the best numbers we have about how many people self-harm include3:

- About 5.5% of adults are estimated to self-harm

- 17.2% of adolescents self-injure

- 13.4% of young adults up to age 24 self-harm

- Recently, experts suggest the number of people between the ages of 10 and 14 who self-harm may be increasing4

- About 1.3% of children ages 5 to 10 self-injure8

Here’s what you should know if you’re a young person who self-harms.

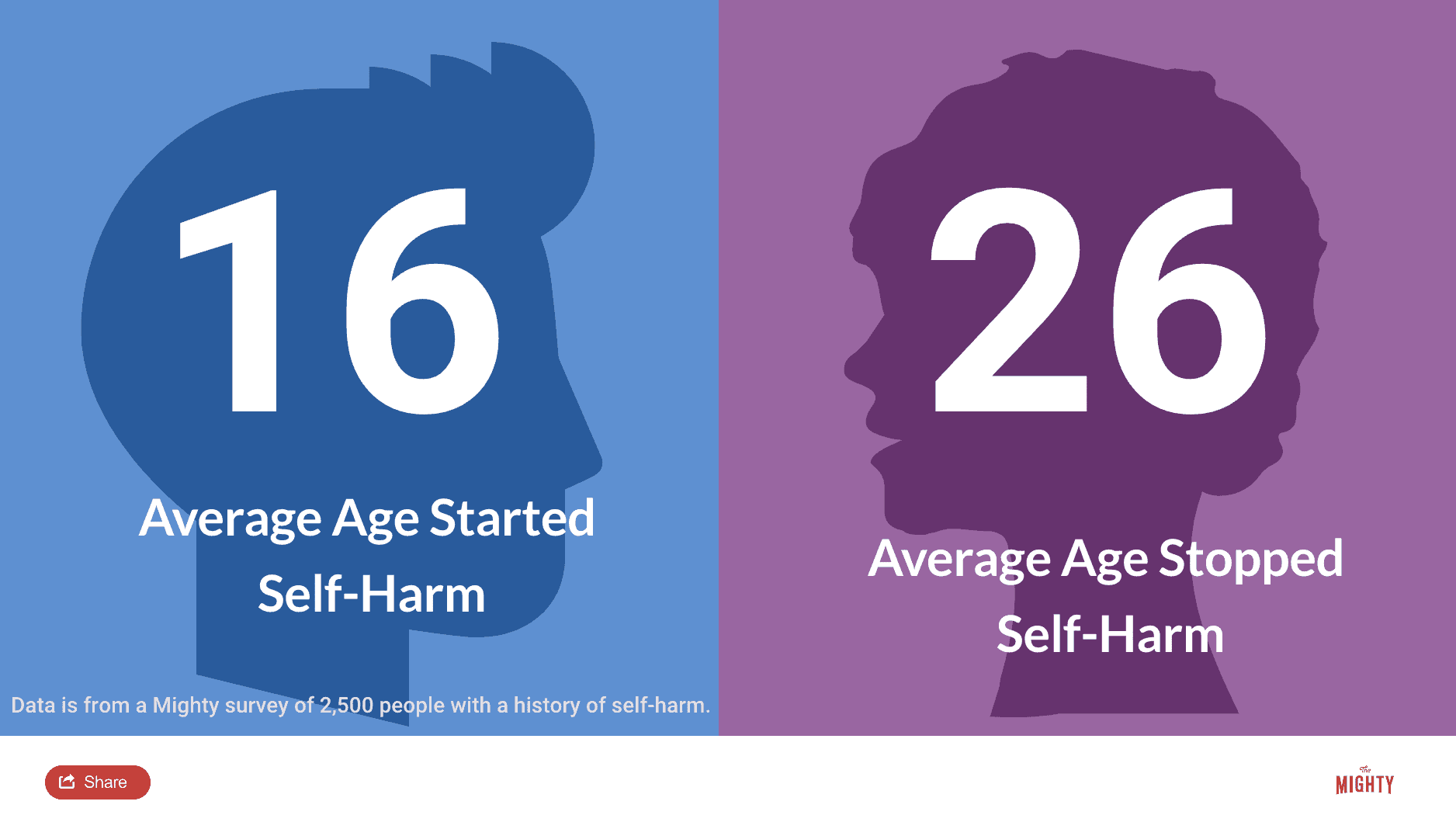

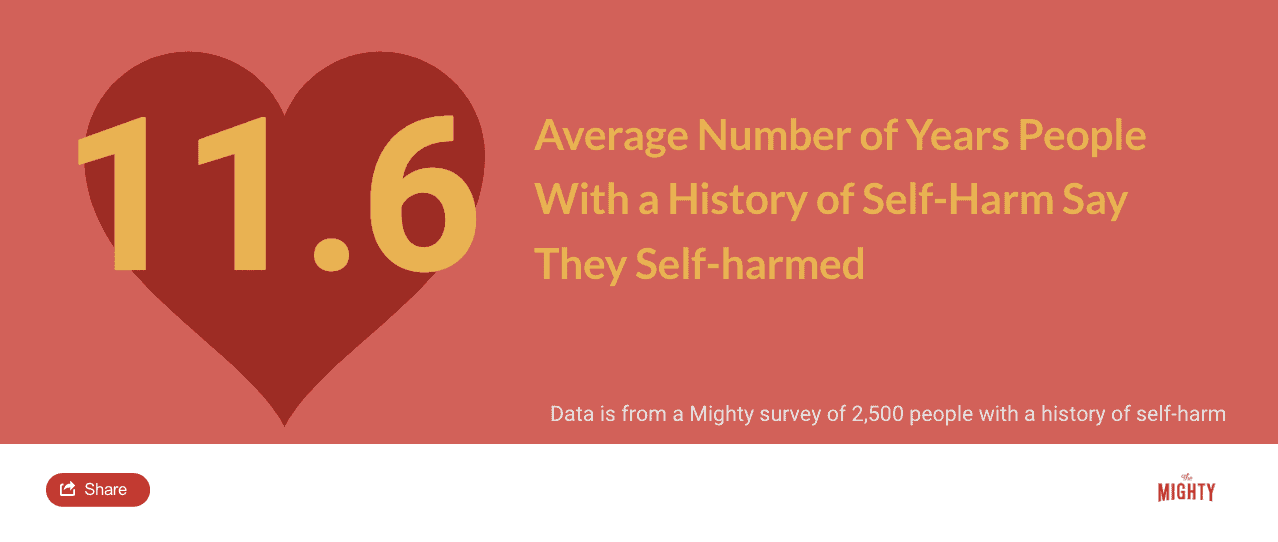

How Long Do People Self-Harm?

Some people will self-injure for years while others may only try it once and then stop. The journey to recover and stop self-harming looks different for everybody, but here’s what we know about how long people self-harm:

- The average age many start self-harming is 15

- A lot of people self-injure for about five years and then stop, though some will continue into adulthood

- Other people may self-injure as teenagers, stop and then start again as adults following a major stressor

- About 25% of people experiment with self-harm once and never try it again

Here’s what you should know if you’re an adult who self-harms.

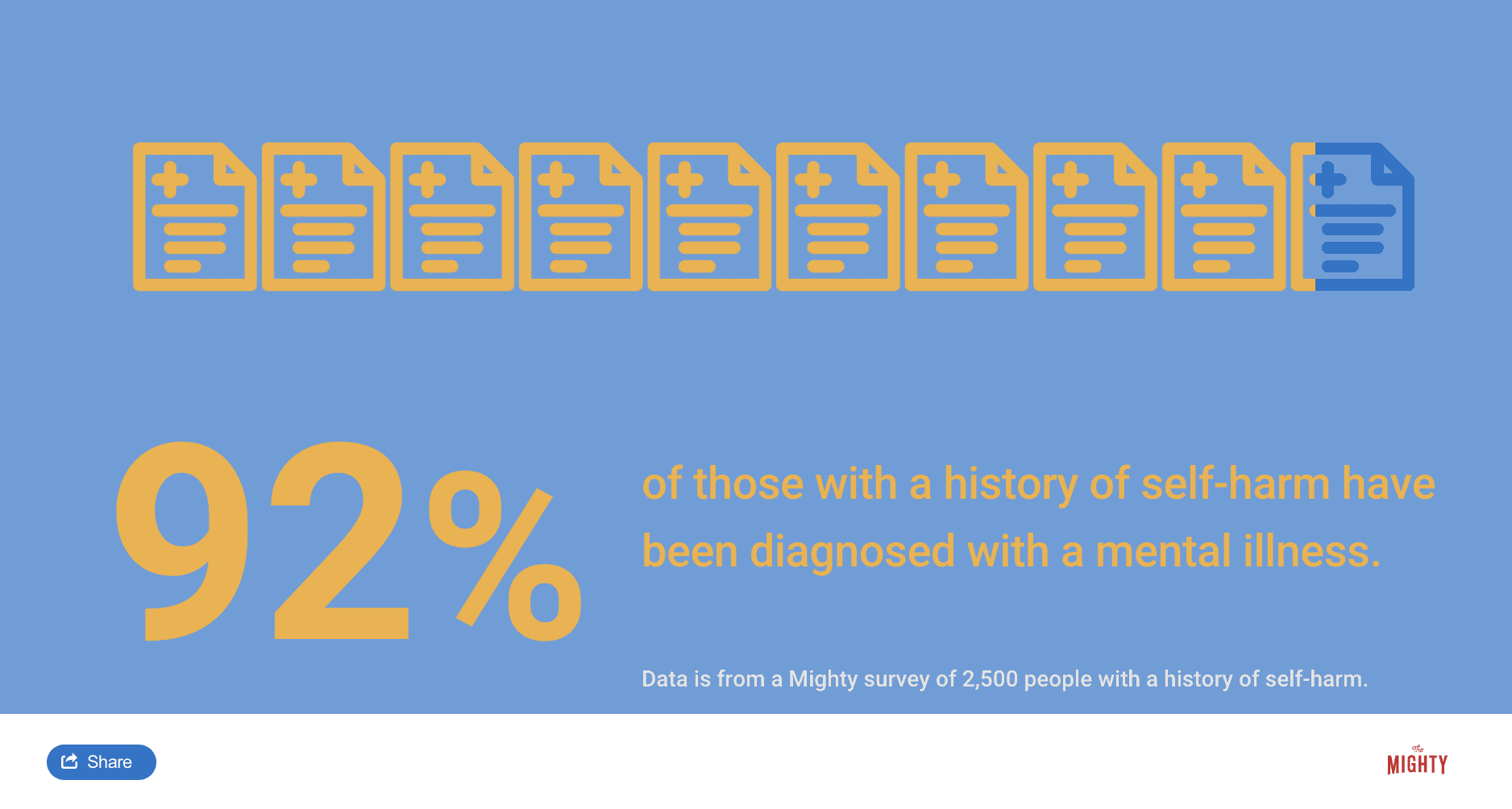

Mental Health and Self-Harm

Just because you self-injure doesn’t mean you are automatically diagnosed with a mental illness. Some people self-injure without a diagnosis of a mental health condition. But there is a strong connection between living with a mental health condition and self-harm.

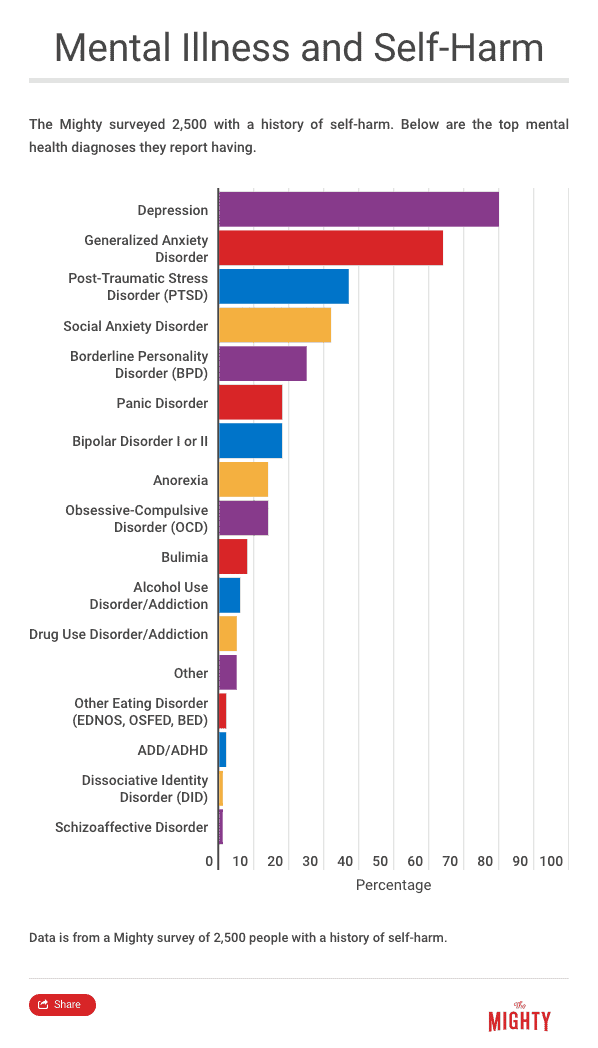

What Mental Illnesses Are Related to Self-Harm?

Self-harm has been linked to a variety of mental illnesses, including:

- Borderline personality disorders

- Eating disorders

- Substance use disorders

- Bipolar disorder

- Depression

Self-harm has long been associated with borderline personality disorder (BPD), the only diagnosis in the DSM that includes self-harm as a potential symptom.1 But experts are learning there’s more to the story. One study found that 80% of adolescent participants who self-harmed didn’t meet the criteria for BPD.9

About 25% of those with an eating disorder self-injure and vice versa.15 In many ways, eating disorders and self-harm can serve a similar function — to manage uncomfortable emotional states.10

Some mental health professionals find that once you address an eating disorder, self-harm might become an area of focus. Or the other way around. You might stop self-harming or be in recovery for an eating disorder but developing healthy emotional coping skills is vital to ensure you stay on the path to healthy emotional regulation.8

Similarly, there’s a strong connection between substance addictions and self-harm. Many times, people report they use substances to change the way they feel, either to dull unwanted feelings or get to a place that feels “high” and therefore a little more comfortable.

Like with eating disorders, substance abuse and self-harm may give you a sense of control over feelings and situations that seem overwhelming and are hard to deal with. It might feel like an escape from painful emotions when you just don’t know what else to do.8

You also have a higher risk of self-harming if you live with depression or bipolar disorder.14, 15 Considering both of these conditions involve uncomfortable mood states, it makes sense that self-harm might become a tool to get some relief from the hopelessness or even numbness of depression or the extreme highs and lows of bipolar disorder.

Regardless of your diagnosis, having a mental illness puts you at a higher risk of self-harm than those without a mental health condition.14

Related:Exploring the Connection Between Psychosis and Self-Harm

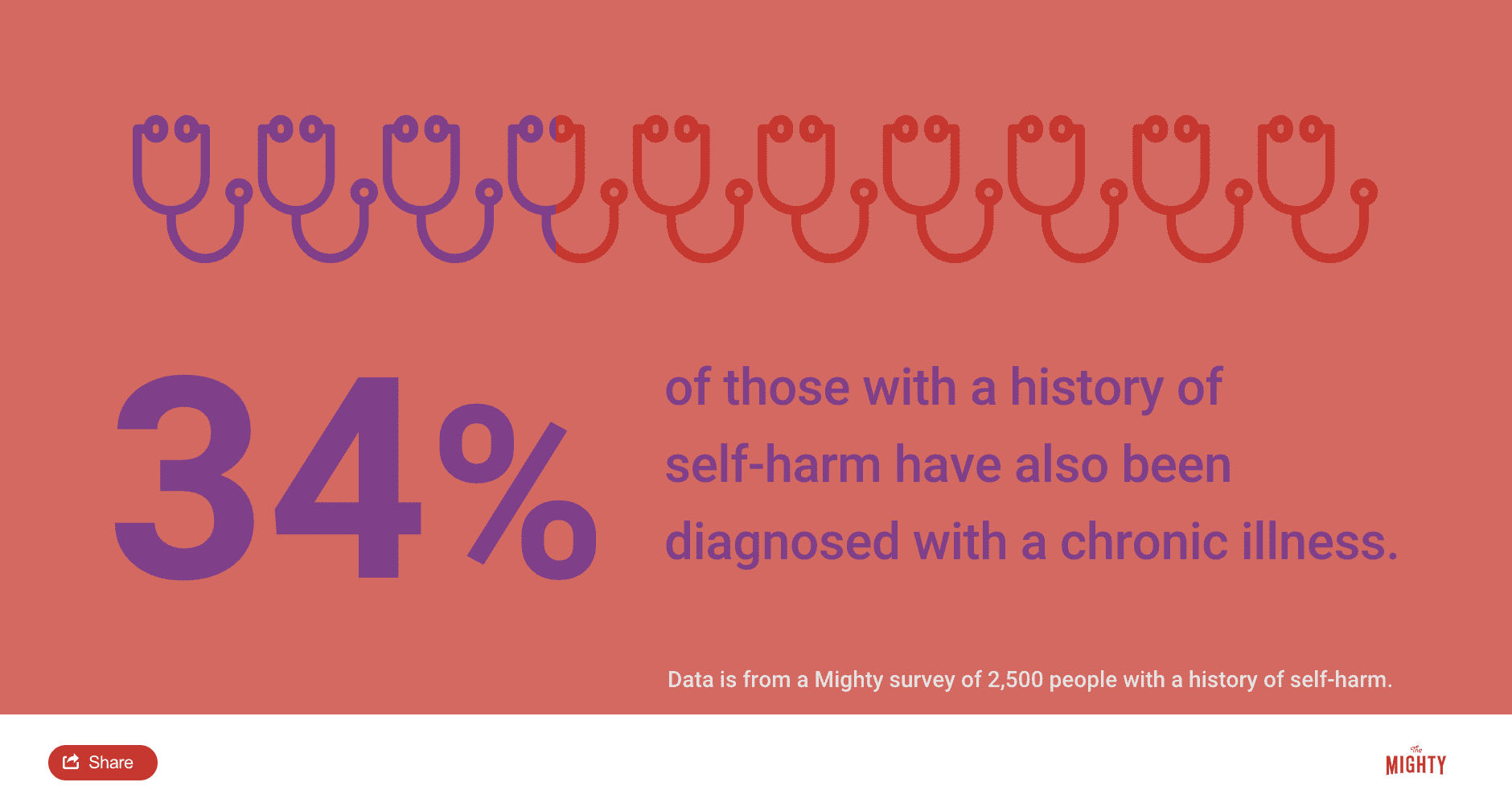

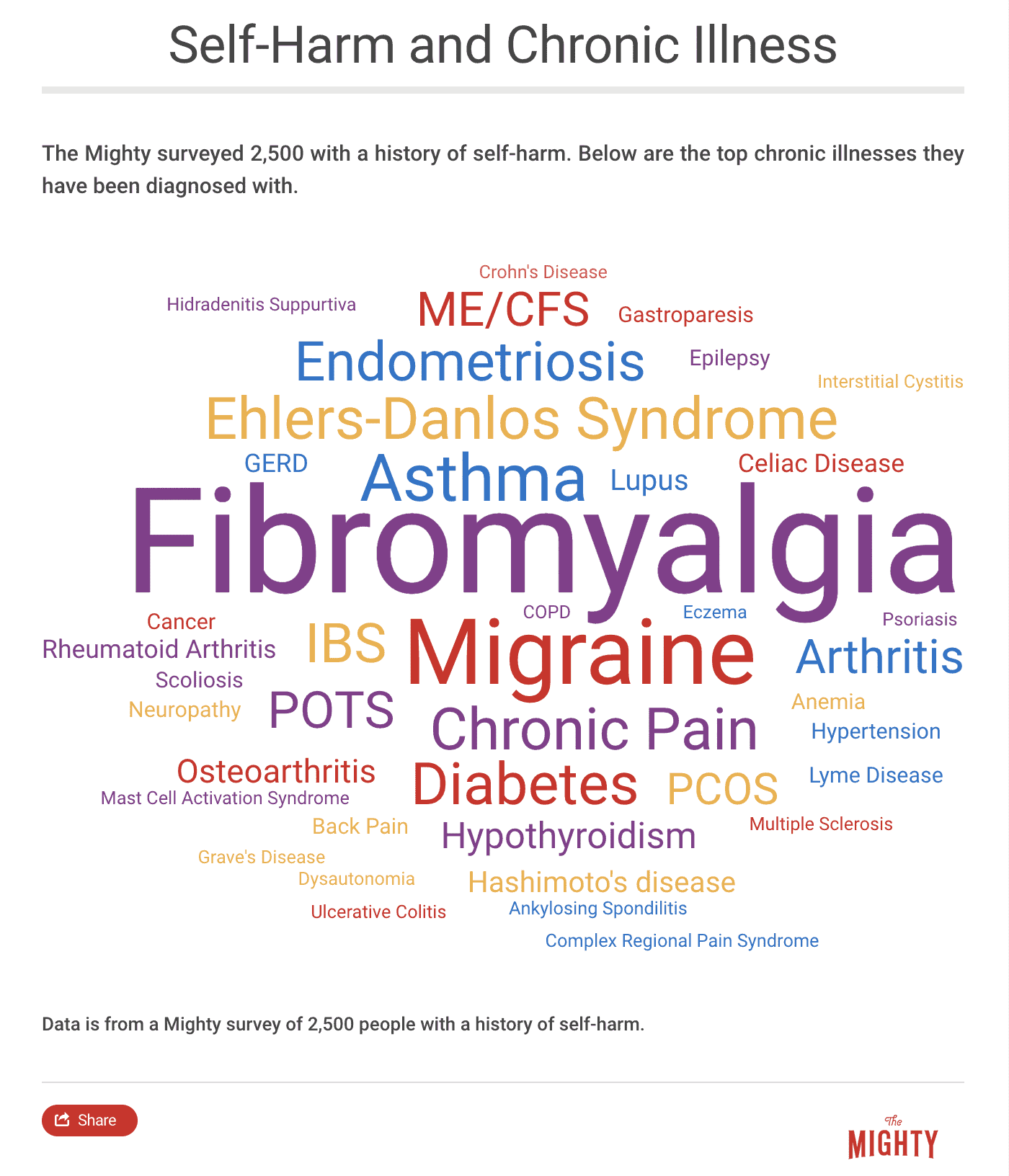

Chronic Illness and Self-Harm

There’s also some connection between self-harm and chronic illness.8, 10, 14 Living with a chronic physical condition can be stressful and lead to many of the same intense emotions or hopeless thoughts that can lead to self-harm. In addition, sometimes you might get mad at your body for being sick, and some don’t know how else to express that anger so they take it out on their body and self-injure.4

Self-harm can also be a way to feel more in control of your body — you decide when to cause physical pain. Other conditions like multiple sclerosis or fibromyalgia have a strong connection to mental illness as a secondary diagnosis.14 So your chronic illness might trigger a mental health condition, which also puts you at risk.

One study found that living with certain chronic illnesses put you at higher risk for self-harm, including:

- Epilepsy

- Asthma

- Migraine

- Psoriasis

- Diabetes

- Eczema

- Rheumatoid arthritis

However, based on responses from 2,500 people who responded to The Mighty’s self-harm survey, most said their self-harm was not related to their chronic illness. 14

Autism and Self-Harm

Autism is associated with a form of self-harm generally called self-injurious behavior (SIB). The reasons you self-harm if you’re on the spectrum could be a little different than how the DSM describes it.

For example, if you’re on the spectrum, you may self-injure because13:

- You’re dealing with a medical issue like an ear infection

- A reaction to an overwhelming specific event or stimulus

- To self-regulate through repetitive motions

Regardless, like all self-harm, SIB can cause significant distress, lead to bullying or social misunderstandings or have medical consequences.12

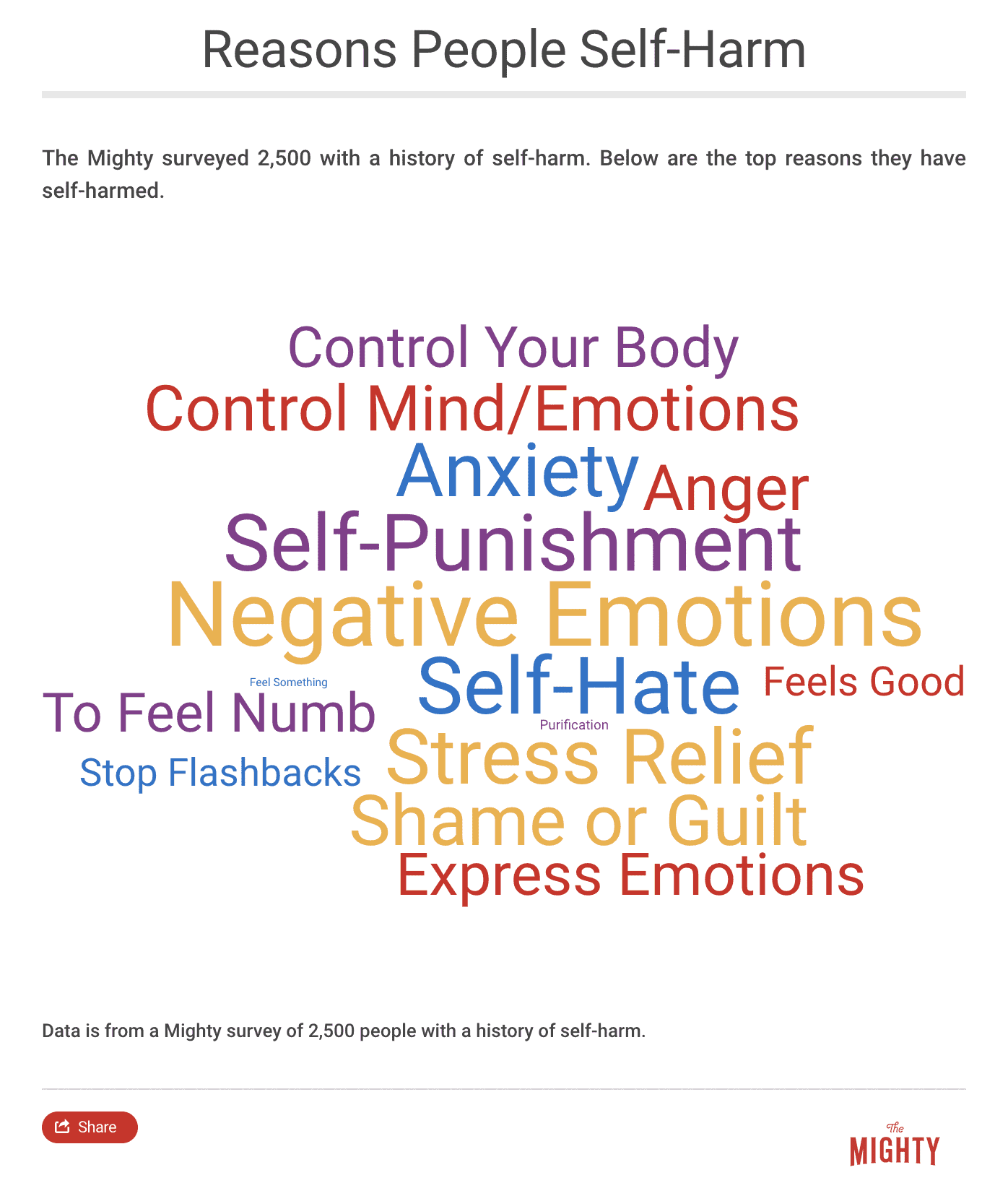

Why Do People Self-Harm?

The DSM and mental health professionals might use phrases like “emotional regulation” to describe why you self-injure, but you probably already know it’s more nuanced. One time you might feel too much, another day too little. After a big fight with a parent or partner, you just want to express what you couldn’t say during the argument. The reason you self-harmed might have been different each time. What your reasons likely have in common is the desire to feel better.

To Get Relief From Emotional Pain

The most commonly reported reason for self-harm is to feel relief from intense emotions like5:

- Sadness

- Anxiety

- Frustration

- Anger or rage

Some people also self-harm as a way to regulate intensely positive or “high” states such as mania.5 Other times your emotions might feel like a giant “blob” and you can’t tell them apart.10

It’s also sometimes easier to deal with physical pain as opposed to emotional pain. When emotions are that intense, self-harm may feel like it decreases the intensity of your emotions to a more bearable level.8, 11

You might not know any other way to express or process intense emotions to feel better without self-harm. However, self-harm provides only temporary relief, so it’s important to find ways to cope with those intense emotions over the long-term that keep you safe and healthy.

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Write your feelings out in a journal

- Go for brisk walk

- Play a game on your phone

- Blow bubbles

- Listen to music

To Stop Feeling “Numb” or “Empty”

You might self-injure to feel anything at all. You may feel “empty,” “numb” or dissociated, or like the world around you isn’t real, like you’re in a movie.11, 15 You may experience a floating sensation where you don’t feel real either. This isn’t always comfortable, and at times you may have found the intense physical sensation of self-harm brought you back into your body to feel more solid or real.

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Pick a random object and list everything you could use it for

- Bite into a lemon or lime

- Use your favorite essential oil or scented lotion

To Punish Yourself

Self-harm might be a way you have punished yourself when you have had intensely negative thoughts about yourself, like you’re not good enough or worthy of being in your relationships. Self-injury might seem like a way to express self-loathing or self-criticism because at times you think you deserve the pain to punish yourself for perceived flaws or errors.

Self-harm can shift your focus from repetitive, unbearable thoughts to physical sensations. Research shows using self-harm as a punishment is likely the second most common reason people self-harm.11

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Take a cold bath

- Dance

- Make a list of all the good things about yourself

To Stop Suicidal Thoughts

Many people don’t understand the difference between self-harm and a suicide attempt — self-harm is intended to make you feel better, not to cause death. Sometimes when you experience intense suicidal thoughts and don’t know any other ways to cope, you may have relied on self-harm to avert or stop suicidal urges and protect your life.11

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Call or text a friend, family member, therapist or suicide helpline

- Cuddle or play with a pet

- Watch your favorite comedy

- Journal about your feelings and experiences

To Express You Need Support

If you’ve ever self-harmed, there’s a good chance at one point or another somebody accused you of self-injuring “just” for attention. However, self-harm isn’t attention-seeking. It’s support-seeking, a way to ask for help when you can’t find the words.

Self-harm can serve as a way to communicate when you feel you don’t have the words to ask for help and a way to express intense feelings like anger or fear of abandonment.8

Related: What I Want to Tell the Person Who Said I Only Cut Myself for Attention

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Write a letter to a person you want support from to express your needs even if you never mail it to them

- Visit a friend and make a plan to go to your favorite restaurant or do your favorite activity together

- Make a list of your favorite things to do with friends

To Feel In Control

In difficult or traumatic situations, you may feel like you have no control over what happens to you or your body. When you self-harm, however, it can seem like you’re reclaiming your body by causing injury to yourself instead of waiting to be hurt by someone else. It may feel like you’re able to take back your power. You might even find yourself thinking that nobody can hurt you as much as you hurt yourself.

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Make a to-do list for your week; don’t leave anything out

- Practice yoga

- Take a shower

- Clean your room

To See Your Pain

When you’re in a lot of emotional pain, you may be really good at hiding so nobody else even knows you’re struggling. Sometimes it’s really important for you to be able to see the pain. Physical injury caused by self-harm is a way to make emotional pain look and feel real, which can feel validating and become a visual representation that you are taking some kind of action to solve what’s wrong.8

Emotional pain is difficult to quantify or measure for yourself or others, so your wounds and scars are a way to prove, even to yourself, that what you’re going through is hard, especially if it feels like nobody else understands.8 It also becomes a visual representation that you are taking some kind of action to solve what’s wrong.8

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Draw using colored pencils, markers or crayons to express what you’re feeling

- Write about your experience

- Curate a music playlist

The Ritual of Self-Harm

The steps you go through before and after self-harming might also be part of what makes you feel better. Many people, for example, will have a certain order to do things in around self-harm, like a ritual.15

The routine may become part of how self-harm calms you down. Just going through the motions — perhaps because you know there’s relief coming — becomes part of why self-injury works for many people.8

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Work on a craft project

- Practice meditation

- Cook your favorite meal

To Heal Your Pain

When you’re in emotional distress, it’s normal that you might long for someone to heal the pain you’re feeling. Or you wish there was a way you could take away your own pain. That’s why you may find that taking care of self-harm wounds is another way that self-injury might help you feel better. Not only can self-harm make emotional pain visible, but by tending to wounds and watching them heal, you can vicariously heal the emotional pain they represent.8

Coping mechanisms that might help if you feel this way:16

- Take a warm bubble bath

- Drink warm tea or hot cocoa

- Cuddle up on the couch with a blanket or stuffed animal

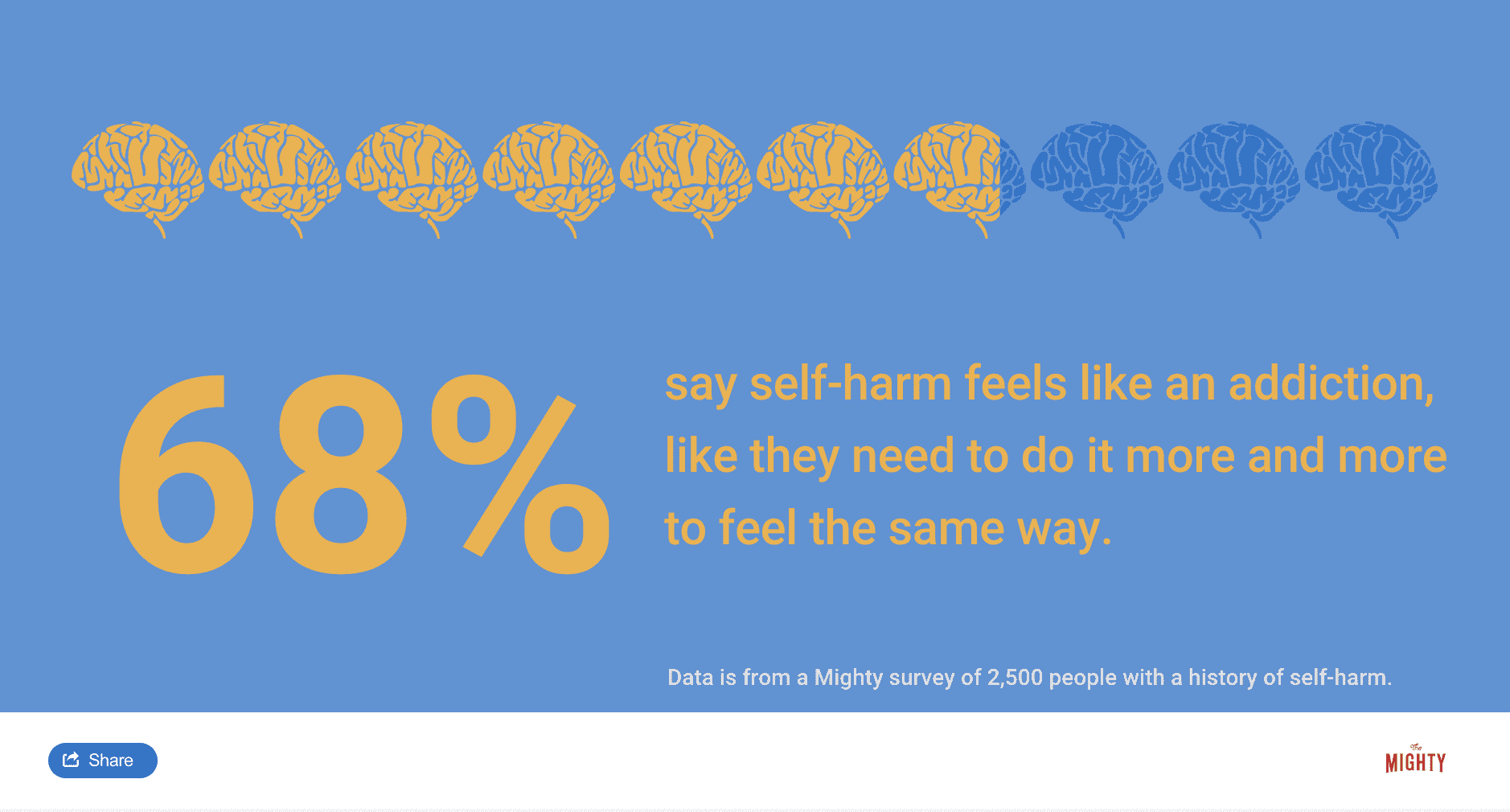

Is Self-Harm an Addiction?

Have you ever noticed that sometimes self-harm feels almost like an addiction? It might become the only way you know how to calm down. Over time it could take more and more self-injury to get the same relief. It becomes a habit, and you become dependent on it — you can’t imagine making it through life without it. When you want to resist or stop self-injuring completely, it’s not always that simple.15

If this sounds like you, you’re not alone. Many people who self-harm come to rely on it in the same way others describe their addiction to alcohol or drugs: it’s your best friend, you can’t imagine life without it, it’s your go-to when you’re having trouble and it serves many functions.15

Though self-harm can be feel like a highly addictive behavior, in technical terms it’s not.8 One of the core criteria of an addiction is that it’s a substance and it’s “externally generated.”15 Unlike self-harm, substances make us feel better because they are a chemical we add into our system.

The relief you feel from self-harm, on the other hand, is caused by your body’s internal response to pain. Its effects, therefore, are “internally generated.” Self-harm is more about avoiding uncomfortable emotional states rather than attempts to “get high.”10

Another major difference between self-injury and substance addictions are the cravings you might feel. When you have a “craving” for self-harm, it’s more likely in response to a specific stressor.15 That could be a wave of intense feelings, a heated argument with a friend, a bad day at work, a triggering trauma response or the out-of-control feeling of being too high during a manic episode.

But if you’re feeling OK and balanced, you’re not as likely to self-harm. It has a pretty specific purpose, and some people can go weeks, months or years without self-injuring if they don’t experience a trigger.15 If you have a substance use disorder, however, you likely crave alcohol, drugs and other substances anywhere and anytime even without a trigger.

Myths About Self-Harm

Despite how much work has been done in the last 20 years to better understand self-harm, there are still many myths out there about what it is and isn’t. Chief among these are that people still think it’s always a suicide attempt, you self-harm only for attention or to manipulate people, it’s only young white women who self-harm, and more. Here are some all-too-common self-harm myths worth debunking.

Myth: Self-Harm Is a Suicide Attempt

Self-harm is generally not a suicide attempt. You may even use self-injury as a way to stop having suicidal thoughts. In most cases, self-harm comes from a healthy, normal human desire to feel better, which is something you can work with.15 It’s very different than, “I can’t take this anymore, I need to leave the planet.”15

Self-harm comes from a strong desire to make your life more manageable. You just need to find alternatives to self-harm to keep you healthy and safe in the long run. That said, self-harm is a very strong risk factor for suicide, one of the most highly correlated risk factors.8, 10, 11, 15

The statistics:

- Studies have shown that approximately 70% of adolescents who self-harm have made at least one suicide attempt9

Even though self-harm shouldn’t be confused with a suicide attempt, it’s critical to get help to prevent growing distress that doesn’t feel like it can be resolved. Self-injury should always be taken seriously.11 The injury itself should be assessed to see if immediate medical care is necessary and resources for treatment should be sought.

Myth: Self-Harm Is Attention-Seeking or Manipulative

Self-harm has long been misunderstood as “just” an attention-seeking or manipulative behavior. However, research shows that self-injury is often done in secret, and those who self-harm might not tell anybody about it at all.8

What the research says:

- Some experts have found that only about 16% of college-age students who self-harm told their therapist about it10

- Many who self-harm and have a wound that requires emergency medical care won’t go to the ER to keep the self-injury secret8

There are often a lot of reasons to keep self-harm secret, which can range from everything from feeling ashamed or invalidated, fear someone might make you stop, concerns that you’ll get in trouble or being hospitalized.10

We can stop this stigmatizing myth about attention-seeking by changing our perspective from “attention-seeking” to instead “support-seeking.” If one of the reasons you self-harm is to communicate to others, even unconsciously, it’s because you’re looking for and needing support from someone who really cares.

Related: What I Want to Tell the Person Who Said I Only Cut Myself for Attention

Myth: Only People Who Are Abused Self-Injure

Not everyone who self-harms has been abused. While some research has shown that as many as 79% of adolescents who self-injure have experienced maltreatment (neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse and emotional abuse) in their youth, this doesn’t mean only people who have experienced abuse or trauma self-harm.6

Some clinicians who specialize in self-harm found that while some who self-injure were abused, the majority were not.8 And, contrary to popular belief, research shows that sexual abuse is the least likely form of childhood maltreatment to lead to self-harm.6

What the research says6:

- Neglect was found to have the highest correlation with more severe self-harm and to be a high-risk factor for females

- Both males and females were more likely to self-harm if they were physically abused

One potential reason for the high correlation between self-harm and childhood exposure to abuse is the experience can be incredibly distressing and lead to overwhelming emotions or feeling out of control. It’s hard to know how to cope, so people may turn to self-harm to help regulate these intense emotions.

Myth: Only “Emo” Female Teenagers Self-Harm

Anybody can self-harm, regardless of gender, sexual orientation, race or age. It’s not just white “emo” or “goth” teenage girls. People of color, boys and adults self-harm.10

It is true that if you’re under the age of 25 you’re more likely to self-harm, yet 5.5% of adults self-injure. There is no set rule — someone may self-injure at age 13, stop and then start again in their 50s after a major stressor.

Self-harm is a tool you may have learned to regulate your emotions, and the need to manage intense emotions doesn’t discriminate based on your identity. You’re more vulnerable to begin self-harming as a young person while your brain develops and you’re still learning other skills to regulate emotions.

However, any number of factors may make it hard for you to stop self-injuring, especially if you’re still dealing with intense emotions or a mental health condition. To assume self-harm is only something done by teenage girls or a teen fad piles additional shame and stigma onto those who self-harm, which might mean they don’t seek help. It also minimizes the seriousness of self-injury and diminishes people’s actual experiences.11

Myth: Self-Injury Is Not Really a Big Deal

Even if you’ve made minor, superficial wounds while self-injuring, it’s not something to dismiss. Self-harm is a way to feel better and any time it becomes a go-to coping skill, it means additional support is needed. A young person who self-harms “a little” one time may go on to severe self-harm if it’s ignored.

An episode of mild self-harm behavior can escalate to more physical damage that can become more dangerous, even without a desire to kill yourself. You might not even know about the self-harm because it’s kept secret.

Even if someone self-harms once, it’s important to understand why they tried it, what they were hoping would happen and figure out if they need extra support or coping skills.10 Self-harm is a major risk factor for further emotional struggle and a higher likelihood of future suicide attempts.

It may at first seem like your child is “only” self-harming because their best friend does it too, but almost everyone who self-harms continues to do it because it makes them feel better. If the person self-harming wasn’t getting something out of it, research shows they generally don’t just keep doing it as “copycat” behavior, especially because self-harm has real-life consequences like permanent scars.

Related:

- Parents: What to Know if Someone You Love Self-Harms

- 11 Helpful Tips From a Parent of a Child Who Self-Harms

You may find self-harm isn’t taken seriously is at the emergency room or by doctors.10 If you’ve tried to get medical care for a self-harm wound, you may have encountered any number of unhelpful responses, but one of the major ones may have been doctors not taking self-harm seriously.

Most medical doctors don’t receive much, if any, mental health training so they’re just as likely to believe all these myths about self-harm as everyone else. For example, when asked about self-harm first aid, one hospital’s entire ER staff didn’t feel like they knew enough about self-harm to provide basic guidance about wound care and when to get additional help. They just recommended calling 911.

Related:

- 2 Things Doctors Shouldn’t Say to People Who Self-Harm

- When a Doctor in the ER Pointed Out My Self-Harm Scars

- When a Doctor in the ER Questioned Why She Should Help Me

- To the Nurse Who Laughed About My Self-Harm Scars

Self-Harm Recovery Is Possible

Even if it doesn’t feel like it right now, recovery from self-harm is possible. With support from loved ones and a therapist, learning new skills for managing big emotions and difficult situations, and a lot of hard work, there is hope.

You may not want to stop right now but working to learn new ways to manage why you self-harm will help you feel better in the long term. No matter what you’re going through, you are not alone.

Learn More About Self-Harm Recovery: For Young People | For Adults | For Parents and Loved Ones | Resources

Updated Sept. 20, 2019

Sources

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Benarroch, E. E. (2012). Endogenous opioid systems: Current concepts and clinical correlations. Neurology,79(8), 807-814. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182662098

- Cornell Research Program on Self-Injury and Recovery. (n.d.). Self-Injury. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/siinfo-2.pdf

- DeAngelis, T. (2015, July/August). Who self-injures? Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2015/07-08/who-self-injures.aspx

- Edmondson, A. J., Brennan, C. A., & House, A. O. (2016). Non-suicidal reasons for self-harm: A systematic review of self-reported accounts. Journal of Affective Disorders,191, 109-117. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.043

- Fleming, M., & Aronson, L. (2016). The relationship between self injury and child maltreatment. Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/the-relationship-between-self-injury-and-child-maltreatmentfinal-1.pdf

- Franklin, J. (2014). How does self-injury change feelings? Retrieved from http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/how-does-self-injury-change-feelings.pdf

- Goodman, Joan. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- In-Albon, T., Ruf, C., & Schmid, M. (2013). Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for the DSM-5 of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in Female Adolescents: Diagnostic and Clinical Correlates. Psychiatry Journal,2013, 1-12. doi:10.1155/2013/159208

- Lader, Wendy. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Lewis, Stephen. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Minshawi, N., Hurwitz, S., Fodstad, J., Biebl, S., Morris, D., & Mcdougle, C. (2014). The association between self-injurious behaviors and autism spectrum disorders. Psychology Research and Behavior Management,7, 125-136. doi:10.2147/prbm.s44635

- Sarris, M. (2017, February 08). Challenging Behavior in Autism: Self-Injury. Retrieved from https://iancommunity.org/aic/challenging-behavior-autism-self-injury

- Singhal, A., Ross, J., Seminog, O., Hawton, K., & Goldacre, M. J. (2014). Risk of self-harm and suicide in people with specific psychiatric and physical disorders: Comparisons between disorders using English national record linkage. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine,107(5), 194-204. doi:10.1177/0141076814522033

- Whitlock, Janis. (2018). Self-injury [Telephone interview].

- Whitlock, J. & Kilburn , E. (2009). Distraction Techniques and Alternative Coping Strategies. Retrieved from http://selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/distraction-techniques-pm-2.pdf