The Problem With the Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids to Patients With Chronic Pain

First, let’s define our terms. What exactly is “evidence-based medicine” or EBM? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group communicated in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) that EBM “de-emphasizes intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale as sufficient grounds for clinical decision making and stresses the examination of evidence from clinical research.”

Now, let’s dig in.

For those of you who may be unaware, in 2016 the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published a guideline for prescribing analgesics for chronic pain. The guideline was ostensibly only meant for primary care physicians but in the wake of all of the hysteria surrounding analgesic medications, millions of patients have been forced to lower their dose to 50 to 90 milligrams based on the unscientific “Morphine Milligram Equivalent” or MME, while many others have been forced off of analgesics entirely with devastating consequences.

What is the Morphine Milligram Equivalent (MME)?

One of the linchpins of the CDC’s controversial guideline is the MME, but what is it? The MME is essentially a conversion chart that was created to guide providers on the different “strengths” of certain analgesics compared with morphine. Only, as many physicians and scientists have pointed out, CDC did not take bioavailability, half-life and metabolism, drug to drug interactions, or genetics into account when they developed the MME.

As Dr. Josh Bloom Ph.D., the Director of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Science at the American Council on Science & Health (ACSH), points out:

“Although the conversion table seems to be straightforward enough, it is based on an assumption that all opioids behave similarly in the body. But this assumption could not be less accurate. Once we see the profound differences in the properties of the drugs and the difference between individuals who take them it becomes clear that not only is the CDC chart flawed, but the MME is little more than a random number.”

Dr. Bloom also made it clear that “flawed science yields meaningless results,” and as I pointed out in “Providers Not Allowed Fully Autonomous Decision Making,” this is exactly why bureaucrats should not be developing “best practices” or guidelines for physicians for nationwide implementation and calling it “science.”

I strongly encourage all of you to read “Opioid Policies Based On Morphine Milligram Equivalents Are Automatically Flawed” because it gives an absolutely incredible explanation for why the MME is unscientific in terms most will understand via simple analogies.

Methods Used During Development Phase Cast Doubts on Guidelines’ Validity

Richard Lawhern, Ph.D. wrote in August 2016 in the National Pain Report that he had located some of the “research” that was used to justify and develop the guideline and provides some very compelling arguments which cast doubt on the methods used in the development phase:

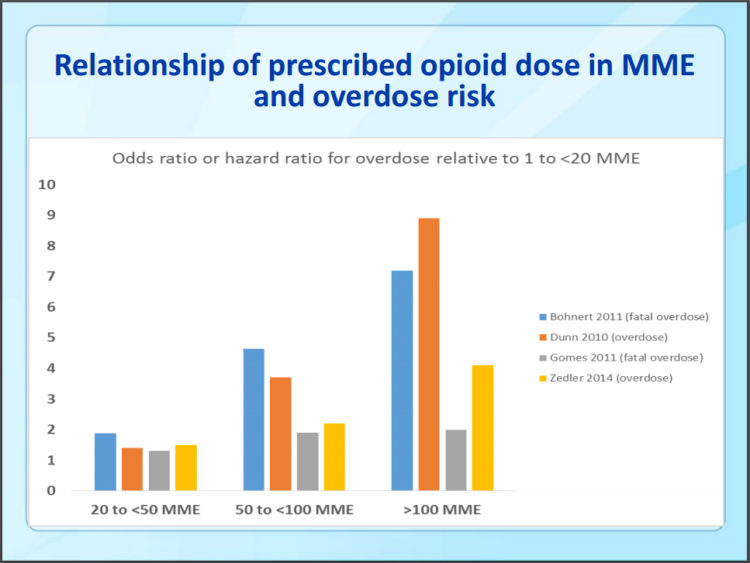

“Deborah Dowell, a Senior Medical Advisor in the CDC Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, wrote a briefing of the Consultants Working Group’s major recommendations that includes a summary chart labeled ‘Relationship of prescribed opioid dose in MME and overdose risk.'”

Dr. Lawhern goes on to point out that in this chart:

“…four published studies are compared. Apart from the unexplained protocols behind those studies, the results are internally inconsistent and wildly at variance between the four. One study of reveals a leveling off of overdose risk at 50 mg Morphine Milligram Equivalent Daily Dose, while the others claim a significant further increase in risk at 100 MME or higher.

What we don’t know is HOW MUCH higher the dose increase was in each of the four studies, OR on which opioids.”

Dr. Lawhern also wrote in ACSH in March 2017 in regard to both Congress mandating use of the Guideline by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) seeking to mandate it for insurance reimbursement, that this was happening “despite the fact that the methodology of MMED is itself considered a meaningless medical mythology by many experts in the field.”

A deceptive bureaucratic maze adds deep insult and possibly criminal intent to this obvious injury. Many of the core assumptions of the CDC guidelines are supported by only the weakest medical evidence — and others are clearly contradicted by the evidence. Medical professionals have published sharp criticisms of the CDC guideline and of the anti-opioid biases of consultants who wrote the document. A recent paper in Pain Medicine [ref: Pain Med (2016) 17 (11): 2036–2046] offers analysis that shows the writers of the Guideline deliberately distorted the evidence they gathered.

CDC consultants performed a literature review on the effectiveness and risks of three classes of treatments for severe chronic pain: opioids, non-opioid medicines like Tylenol, and behavioral therapies like rational cognitive therapy. Based on this review, they declared that there is very little evidence that opioids work for pain over long periods of time. But they neglected to inform readers that they had rejected any study of opioid medications that hadn’t lasted at least a year, then declaring that there was no proof that opioids are effective over the long term. But they did NOT reject studies of non-opioid medications or behavioral therapies that were similarly short.

As the Pain Medicine paper states, ‘To dismiss trials as “inadequate” if their observation period is a year or less is inconsistent with current regulatory standards… Considering only duration of active treatment in efficacy or effectiveness trials, published evidence is no stronger for any major drug category or behavioral therapy than for opioids.’

This didn’t keep the writers of the CDC Guideline from recommending that non-opioid treatments be favored over opioids, despite lack of evidence that they work. Nor did it keep the writers from exaggerating opioid risks — using the term ‘overdose’ no less than 150 times in their biased and unscientific practice standard.”

“Evidence-Based” Recommendations Deviate Significantly from Established Methodology

According to Jeffrey Fudin, Mena Raouf, Erica L. Wegrzyn, and Michael E. Schatman Ph.D.:

‘The CDC used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework for producing evidence-based recommendations; however, the guidelines deviated significantly from the established GRADE methodology without associated justification. There is a significant mismatch in the strength of the recommendations made in the guidelines and the supporting evidence. When considering that all recommendations were based on level 3 or 4 evidence yet eleven of the recommendations were assigned grade A, this is a major deviation from the National Clearing House guidelines on levels of evidence and grades of recommendations.”

What Is The GRADE Framework?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) “develops recommendations on how to use vaccines to control disease in the United States…Once the ACIP recommendations have been reviewed and approved by the CDC Director and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, they are published in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR).”

CDC also says that “the method has been adapted,” unfortunately, as Fudin et al. communicated, they did not provide justification. It’s also unclear whether a framework developed specifically for vaccines is appropriate for application elsewhere, especially considering the way in which it was “adapted.”

The CDC Consultants That Performed the Literature Review

The CDC got quite a bit of help implementing their guideline. One name you’ll want to keep in mind is Michael Von Korff. For those who have never heard of this individual, Michael Von Korff is a Doctor of Science who specializes in research and he is also a sitting Board member (Vice President-Scientific Affairs) for Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing or PROP.

PROP has been an extremely controversial actor in how the narrative about the overdose crisis unfolded in the public discourse, as well as behind the scenes with federal agencies such as the CDC and the FDA. PROP’s attempts at public “education” on opioid analgesics that now dominate the narrative in regard to the crisis have been harmful at best and their ideology relating to opioid analgesics, extreme. I will provide examples of the extreme ideological bias that exists at PROP in future articles, however, Von Korff also served as a consultant to Abt Associates, Inc. and the project team from Abt Associates served as a contractor to the CDC for guideline implementation.

Abt Associates has been invaluable to the CDC in regards to both the development and implementation of the guideline and “quality improvement” (QI) metrics. Those who served as consultants to the Abt Associates project team for CDC’s quality improvement initiative are, as far as I can discern, predominantly from PROP, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, and the Oregon Pain Guidance Group, all of which have demonstrated an extreme bias against opioid analgesics.

The CDC’s conception of morphine equivalents was, again, “adapted” from an idea which was first communicated in “De-facto Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain” which we will discuss in-depth in the near future. What is the significance of this paper? Well, Michael Von Korff was one of the authors of that paper and it may be interesting to note that the Center for Health Studies, Group Health Cooperative (Seattle Washington), Kaiser Permanente, and the University of Washington School of Medicine are the three dominant associations for the authors of that paper, Von Korff and Joseph O. Merrill included.

The Washington State Guideline, The CDC Guideline and Extreme Bias

Von Korff, among others, was also an important voice that was leveraged in justifying the Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain, the Washington state guideline for prescribing which is one of the most radical in the country and developed by the Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group (AMDG). The development of this guideline began in 2007, long before the CDC Guideline, and it has had catastrophic results. Those results should have been studied in-depth before the CDC ever considered releasing a similar federal guideline, but that didn’t happen.

It’s interesting that both the Washington guideline, and the CDC guideline, mention the fact that genetic factors and incomplete cross-tolerance are important considerations when calculating MME for dose reduction, taper, or switching analgesic medications, but they don’t seem to see its significance when it comes to calculating this for a patient that does not respond well to a 50 to 90 mg daily “MME” (or less).

In regard to the Morphine Equivalent Dose Table, AMDG says, “all conversions between opioids are estimates generally based on equianalgesic dose. Patient variability in response to different opioids can be large, due primarily to genetic factors and incomplete cross-tolerance. It is recommended that, after calculating the appropriate conversion dose, it be reduced by 25–50% to assure patient safety.”

Why did the CDC seek out the advice of radically biased addiction psychiatrists and others, who are not trained in pain medicine, instead of actual pain medicine experts; especially considering that some may have had some glaring conflicts of interest? As Dr. Lawhern pointed out, there could be criminal intent at play here and that possibility needs to be deeply explored, and swiftly.

Dissent Against Unscientific Guideline by Professionals Has Been Ongoing

I must stress the importance of remembering that the MME is not based on any current scientific understanding. It’s an arbitrary dosing guideline that doesn’t translate well in the real world when it comes to adequate analgesia for individual patients. It’s a one size fits all approach and human bodies unfortunately just aren’t that simplistic. If they were, the guidelines’ implementation, despite dissent from experts, wouldn’t be so egregious and some news articles were already exploring this dissent on a wider scale less than a year after the guideline was published.

Back in January of 2017, The Boston Globe published an article about how doctors are cutting patients off of analgesic medications, even if it harms them, and communicated that their survey found that:

“More than half of doctors across America are curtailing opioid prescriptions, and nearly 1 in 10 have stopped prescribing the drugs, according to a new nationwide online survey. But even as physicians retreat from opioids, some seem to have misgivings: More than one-third of the respondents said the reduction in prescribing has hurt patients with chronic pain.”

The article goes on to state that “the percentage who believed patients had been hurt by reductions in prescribing differed little among specialties: 36 percent of all specialties, 38 percent of family doctors, and 34 percent of internists” and this was back in early 2017. It’s difficult to say how much worse the problem has become subsequently, how many physicians in all specialties perceive these changes currently, or how many patients have been harmed (or even “saved”) by the guidelines in the wake of its implementation; but it may be prudent for the public to begin more aggressively seeking answers to these questions.

There are currently no metrics to track patient outcomes one way or the other that are patient-reported, or really even otherwise, and that’s a problem. The reductions in prescriptions are touted often as some kind of evidence of the guidelines’ “success,” but that is not the only metric that should be considered when deciding on a treatment option for living human beings who are dealing with serious health problems. Would we do this for the diabetic patient that requires insulin? While insulin abuse is not as common as other forms of substance abuse, insulin can and has been abused by some diabetic patients with often fatal consequences.

The National Eating Disorders Association says, “Diabulimia is a media-coined term that refers to an eating disorder in a person with diabetes, typically type I diabetes, wherein the person purposefully restricts insulin in order to lose weight. Some medical professionals use the term ED-DMT1, Eating Disorder–Diabetes Mellitus Type 1, which is used to refer to any type of eating disorder comorbid with type 1 diabetes.”

“The relation between substance misuse and poor compliance with treatment is well established in both general medicine and psychiatry. Although young patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus may have lower rates of comorbid substance misuse, there is direct evidence that their compliance with treatment is poor. Patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus have an increased risk of developing a psychiatric disorder, particularly in the early course of their illness, and treating the psychiatric disorder improves glycaemic control.”

If federal agencies and the media told the truth, they would make it clear that prescriptions are at an all-time low while overdoses are at an all-time high (and expected to climb), and yet, they still claim that most overdoses are the result of “prescription opioids”; and they continue to tout the “success” of their guideline and dare to call it “evidence-based.” After being exposed to some of the more moderate experts who have loudly dissented to the implementation of the unscientific guideline, do you believe it’s “evidence-based” or is it possible there is another agenda at play here?

Conclusion

This trend in federal initiatives that seek to apply these types of one size fits all approaches may be due to the shift from individualized care to “population health,” which is a focus of current public health practice. Unfortunately, this type of approach has simply been catastrophic. It’s not yet clear exactly how damaging these initiatives have been to human health on a mass scale because appropriate tracking and control systems were never put in place before (or after) the execution of these initiatives, however, we will discuss some small scale studies that are beginning to shed light on just how dangerous these policies have been for patients in the future.

One thing is absolutely clear, this is not how any crisis should be managed and anyone who understands disaster planning knows that one wrong decision has the potential to create further assaultive crises in the midst of an already existent crisis, and that’s exactly what’s happened. The response to one crisis has created another crisis that affects a far greater number of people than the original problem that health agencies attempted to “remediate.”

Physicians, scientists and other important stakeholders have repeatedly cautioned, written and admonished the CDC, they have advocated tirelessly in an attempt to mitigate adverse outcomes due to the guideline and those warnings were ignored; every time. CDC barreled forward despite an avalanche of dissent from professionals and patients and now, we’re beginning to see the fruits of that disregard. I’ve already begun to dismantle the claim that the guideline fosters increased ‘safety’ for patients. Please see “Policies Fail on Small Scale, Yet Forced Nationally” for an in-depth look at the harms that have been foisted on the American people.

Photo by Daan Stevens on Unsplash