The Oncology Ward In The Sky

Part 1 of 2 Summer 2020.

Biking west along side roads, I whiffed the hospital complex two blocks away. Industrial cleanser seeps through the black cotton mask. Lock up, walk the final 100 feet. First, disinfect hands. People cluster in an attempt to form a line and follow the signposted instructions. We’re all masked. Security guards mill about, and a nondescript hospital employee guides people where they need to go.

“Do you have an appointment? Where are you headed?”

Centre Intégré de Cancérologie, 14th floor, I’ve got a blood test today.

“Oh, you know you have a separate entrance and elevators right? Here, this way, come with me. By coming in through there, you won’t have to wander the entire hospital and touch stuff that’s “disinfected” even though no one really cleans it.”

Thank you, I say, and ponder the horror of that last statement as I disinfect my hands again though I haven’t touched anything and make my way to the Oncology-Elevators. Two of us are whisked up in a socially-distanced elevator ride. Maximum occupancy of 4, one person per floor-sticker. Upstairs I am greeted by a nurse who asks the usual symptom-probes. The nurse’s right hand brushes up against my palms as she leans in to spray sanitizer and disinfect me once more. I didn’t even press the elevator buttons. A volunteer in a polka-dot bow-tie walks me down the long waiting room to point out the blood work reception desk, which has not moved in the 6 months since I was last here. I was supposed to return sooner, but there’s a pandemic going on.

They’ve been working on adding a third even taller wing to the CHUM. In the waiting room I always look down at the progress. Almost done now. Not just another hole in the ground. I used to get my blood tests done at _Notre-Dame_, an old old hospital opened in 1880. The CHUM built in 2017 has another high capacity blood-draw clinic on the main floor of D-wing, but I’ve never sat there in that glass box within the heart of the skyscraper complex with no view outside for patients. No, for some reason I take the elevator to Oncology. Once though I stayed overnight at the Nouveau-CHUM in an ER hallway on a cot under fluorescents. It was mid-march of 2019. In the morning my managing haematologist was on duty and came to see me at bedside. I said I’m fine. He said _You’re not fine listen to these numbers we’ll up your dose of_ Revolade _and deliver intravenous iron also request an appointment with the gastroenterologist because surely if you’re this anaemic your stomach must be bleeding._ Alright then, I guess. As he discharges me, the doctor jokes about how nice the rooms are up on the 15th floor, as if hospitalization is the right thing to chuckle warmly about. I think he’s well-intentioned and has a good grasp of haematological medicine but I was glad to leave, go home, and spend a month in bed resting while the weather turned warm.

Out the 14th floor waiting-room window I see the sky, the city, beyond. Nearby another patient sits down and opens a book: The Most Beautiful Quebecois Poems. I glance back out and a small brown-speckled spider weaves its web across the glass. From where I’m standing it’s bigger than the construction workers, bigger than the pedestrians, almost the size of the police cruiser two intersections away. Waiting there, refusing to sit, I wonder what good all the poetry in the world will do this single arachnid spinning its home over the city of Montreal.

The blood craw clinic is a resolutely functional and hygienic space. Blood draws occur 7am-3pm M-F. Wait times are short for patients who get blood taken here up high. I ask a nurse how many blood tests a day they’re doing lately. “It depends, but a little over 100.”

We’re checking my auto-immune system, it’s been known to eat away at platelets. Platelets are essential clotting factors, and contribute to homeostasis. When platelets are particularly low, internal bleeding is a risk. When I’m experiencing an auto-immune flare, I get acutely aware of my skin’s surfaces and folds, distracted by specks of the outer world that brush up against it, feeling egg-albumin thin. The circulatory system is a series of veinous corridors, highways, canals, transit arteries carrying blood along. The lightest pressure might bruise and the lightest scrape might tear. So we test. Sharp metal insertion somewhere along the arm. Middling.

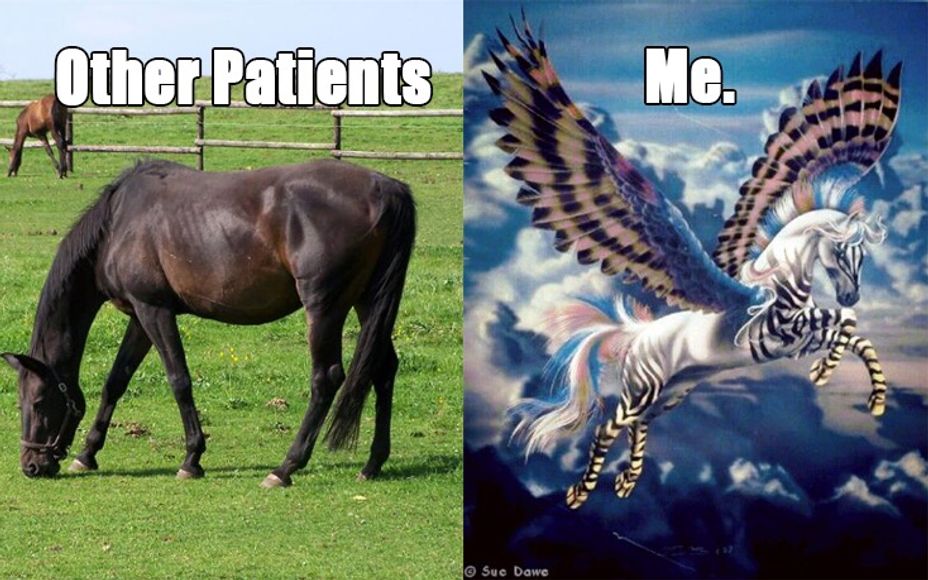

Immune Thrombocytopenia is the medical diagnosis of a bleeding disorder, and the primary symptoms are: bruising in excess of what one would’ve expected for the amount of trauma, or bruises that are totally unexplained. When my daily life is asymptomatic, t