For the past ten years, we’ve had a saying. “It isn’t cancer.” We don’t say it often. It’s reserved for serious things that need a little perspective. We said it a few months ago when my 16-year-old, Isabelle, got into a car accident a week after getting her license and the damage was more than the car was worth (she and the other person were ok). We said it a few years ago when our goldendoodle, Obi, was attacked by a pack of coyotes and needed to be stitched up from head to paws. And I said it a few weeks ago when my husband was worried that the animals were getting at his compost bin. All serious things. But not cancer.

Because pediatric cancers takes seriousness to a new place. One that you can’t imagine. A place that I swear has monsters. My daughter, Emily, had stage IV high-risk neuroblastoma in 2010. One of the worst pediatric cancers a four-year-old can be diagnosed with. The odds of survival are 50/50. To beat it, kids are treated with the harshest therapies in the arsenal. Emily needed six rounds of chemo to shrink the tumor on her adrenal gland and then an eight-hour surgery to remove it. The neuroblastoma was still everywhere, so she had two back-to-back stem cell transplants, which almost killed her. After her transplants, she had 21 rounds of radiation and then six months of an experimental antibody therapy. We spent over 300 nights in the hospital.

It would be difficult to convince me that there could be anything worse than what we lived through. A health crisis, especially one that involves your child, has the power to bring you to your knees in a way nothing else can. It makes you stop, pause, and question everything. It makes you compare it to other really bad things.

Like the coronavirus. A health crisis with parallels. Uncertainty. Germs. Social distancing. And missing important dates, like birthdays and holidays. I’ve watched and listened to people, ones I know and ones I don’t, struggle with the unfairness of it all. They’re depressed, anxious, and angry. They want to know when it will all be over. They want answers. I understand. I’ve been there.

For days and weeks and months after Emily’s diagnosis, I struggled to comprehend that Emily had stage IV neuroblastoma. It didn’t seem possible. My daughter couldn’t have cancer. Other people got cancer. Not Emily. But the doctors kept telling me that indeed she had cancer. Its unpredictability nearly killed me. Anxiety became my normal state of being. My heart beat fast when I was driving in the car or washing my hair in the shower. My mind struggled to make sense of what was happening. I needed answers that no one could provide. I once tried Googling my questions but that only made me feel worse.

During Emily’s stem cell transplants, I’d wait for doctors’ rounds like a higher power was coming to tell me her fate. Pediatric oncologists knew things that I didn’t and I wanted answers to the questions I thought about from morning until night. When will her kidneys recover? When will her white blood cells go up? When can we go home? But most of the time they’d say, “We’re going to need to wait and see.” And that seemed unfair. I had waited 24 hours for answers and they gave me nothing. Basically they said: WE DON’T KNOW.

During treatment, I learned how to properly wash my hands. I didn’t go anywhere without hand sanitizer. Every place seemed dangerous. My fear of germs was only secondary to my fear of cancer. It seemed as though there were liabilities everywhere that could result in Emily’s death. Avoiding them was a job unto itself. But no one in the functioning normal world seemed all that concerned about them. But my mind went wild with the places they were. On my car keys and steering wheel. On the clothes I wore, the handles I touched, and on my shoelaces that would often come undone. I feared germs more than I feared gaining weight. It was that real. When we were given the rules of Emily’s transplants my germ worry turned into a germ phobia. Opened bags of chips or anything else in a bag or box was to be thrown away within 15 minutes of opening it. To-go pizza could not be cut with the knife at the pizzeria. Soft serve ice cream was a no. Deli meat was a no. No visitors. No homemade food from anyone. I stopped touching door handles, community pens, and other people’s keyboards. I wore gloves everywhere and would “borrow” a box of gloves from the hospital to keep in my car when I needed to run into CVS for a script. Normal things were made hard because of the caution I needed to take.

To make matters worse, we had to social distance to keep Emily “safe.” In treatment, it was called isolation. We didn’t have small gatherings. We didn’t eat out. We didn’t socialize with friends. We didn’t let anyone in the house except for the VNA nurse. I went to work because the bank still expected me to pay my mortgage even though my kid had cancer. At work, I kept my distance from people and made them aware that I couldn’t be exposed to their germs. I asked cashiers to sanitize their hands before running through my grocery items. We took our shoes off before going in the house because hospital floors (and just about any floor) carry awful pathogens and bacteria that could have made Emily sick.

Our family became one unit; one person’s germs were everyone’s germs. We sent Isabelle to school and put the school nurse and her teacher on alert that we needed to be aware of any illness in the school. When we were told that a student had the stomach bug we kept Isabelle home. When it was the chickenpox we kept her home again. A social day was being able to have a blood transfusion at the Jimmy Fund Clinic instead of being isolated in the hospital or home. But Emily was on precautions, so Isabelle, Emily and I would cram into a patient room (the size of a regular doctor’s office room) and watch Sponge Bob and Cinderella on a portable DVD player over and over for about six hours. Even the good days wore me down.

At a low point during treatment, when I had nothing left to give, I yelled at my six-year-old daughter, Isabelle because she couldn’t stop coughing. It was late at night and I was scheduled to go to the hospital the next day and couldn’t bring her germs with me. Around the same time, my husband got sick and needed me to stay at the hospital for an extra week so that Emily wouldn’t be exposed. My heart sank. I was desperate for my own bed, bathroom, homemade food, and more than three hours of sleep. But then I felt selfish for thinking of my own comfort because Emily’s emotional health was suffering and nothing I did seemed to help.

Emily knew that her friends and her sister were at school and that she was in the hospital. She asked why she couldn’t see them. She asked why she couldn’t leave the hospital. She sobbed because she missed school and her teacher. She cried because she was desperate to see Isabelle but H1N1 restrictions were in place and no kids were allowed in the hospital. “I’m never going to be able to see her again,” she sobbed. “And I’m never going to be happy ever again.” Being apart wasn’t good for their well being. Or mine.

And then we had to get savvy about dates. Like Easter. And birthdays. Emily “celebrated” her 4th and 5th birthday in the hospital. I was angry on her 4th. I was more angry on her 5th. Yet there was nothing I could do other than change the day we celebrated it. Her 4th birthday was anticlimactic because she was getting hit with massive chemotherapy. My husband told me that I cared more about celebrating it than she did. He was right. But on her 5th birthday, she was on the trial part of her treatment, so we waited a month and had a big party in our backyard when she was finished.

Yet the only thing that mattered when Emily was sick was making the cancer go away. Nothing else mattered. Not Isabelle’s grades at school. Not my hair that desperately needed highlights. Not the upkeep of our house. The only thing we thought and cared about was a healthy, cancer-free Emily. We didn’t care about little things. And everything else was little.

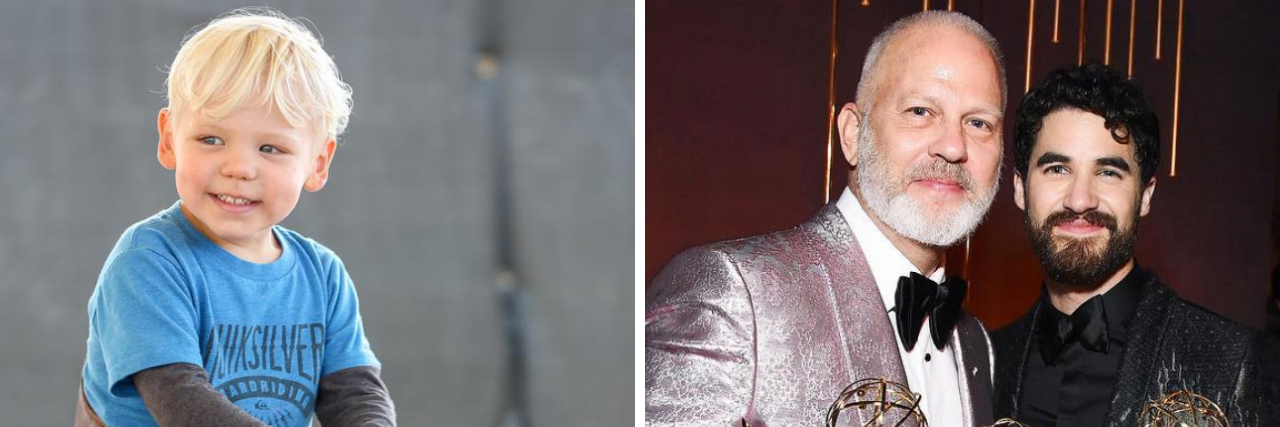

And after 18 months, Emily was deemed “cancer-free.” But the cancer left a trail in its wake. She was left with stage three kidney disease, a 65% bilateral hearing loss, estrogen of a post-menopausal woman, stunted growth, hair that didn’t grow back in well, and wobbly teeth that won’t support braces. The cancer is gone. But not without reminders that it came. And that it could return.

I’ve listened to people complain about the pandemic. I get that they’re upset because they’ve been unable to eat out or go to a movie for months. I understand that wearing a mask is uncomfortable and that keeping socially distant in a store is almost impossible. I know that people want to be able to get their hair cut, go to the gym, and sit down and enjoy their coffee at a Starbucks. I want those things too. But they’re little things. Inconveniences. Things that we can live without. It’s hard to “see” this without perspective. cancer gifts you with it. Perspective may be the one positive thing that cancer leaves behind.

Perspective has allowed me to see that the pandemic is bad. But cancer is worse. Be grateful if you can’t tell the difference.