Finding My Authentic Self at the Intersection of Queerness, Neurodiversity and Disability

“Pregnant women only,” the authoritative voice rang out from behind, pitched with condescension. “Pregnant women only,” echoed another voice, this time from the front of the line; one of two store enforcers had spoken up.

This wasn’t the first time I’d seen individuals turned away from the Target Vulnerable Persons line — so called because it was meant to be inclusive of those the CDC determined “Vulnerable or At-Risk” — nor would it be the last. They weren’t visibly disabled, and so they were rebuked.

Most of the time, the public assessment was correct — these people weren’t disabled. But there are notable exceptions to this assumption, and I have been one such exception on multiple occasions (though not all of them occurred in said Target line, of course). I wanted to speak up on behalf of all those with invisible disabilities, those who might find themselves fighting a system that ought to be working to their advantage, but I couldn’t muster the energy. Abashed, I continued my day.

On that same excursion, I encountered a person who exclaimed incredulously that I had filled up my cart quickly: presumably something a “properly” disabled person shouldn’t be able to do. In their mind, I must be gaming the system. Again, I said nothing. But, in fact, I couldn’t manage that kind of speed: my sister had contributed the majority of the items. Nevertheless, an able-bodied person wouldn’t be expected to provide this kind of defense (nor asked whether they deserve to be there, as I so often have been).

This is just one of many indignities that disabled individuals experience on a routine basis whenever they engage with society. And, I have to say, Target is the most accommodating store to which I’ve ever been.

For much of my life, I’ve been disabled in some capacity. Fibromyalgia, partial thyroid hormone resistance, joint hypermobility syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, allergies; these are the strings that tugged invisibly at my mind and body, slowly weakening my resolve. Pain, exhaustion, tachycardia and chronic deconditioning have made even the tasks I’d once viewed as simple to be incredibly complicated and difficult. Now when I go to the zoo, or to a convention, I use a wheelchair. Typically, I don’t go at all.

I’m also autistic, one of many traits that put me at an increased risk for the abusive relationship that eventually ravaged my life. I was 17 when it all came crashing down. Mental illness inevitably followed — if it hadn’t preceded it — as did unrelated abuse and relationship difficulties. Generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, complex post-traumatic stress disorder, dependent personality disorder — the list grew longer by the year, and now feels overwhelming to simply mention.

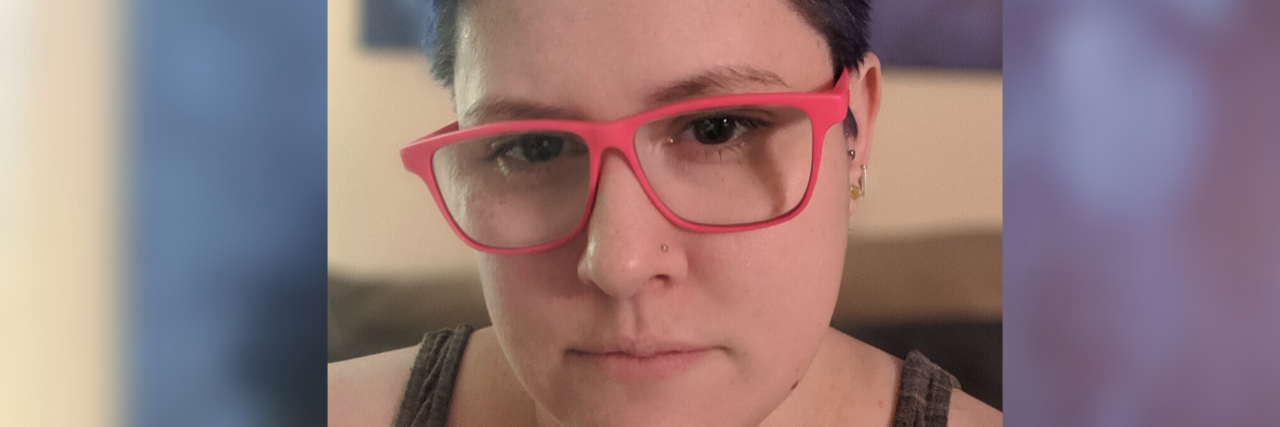

Because of all this, I never worked beyond a summer internship and a few work-studies. I never learned to drive. I’m lucky to have qualified for disability benefits. I can’t even begin to imagine coming out with all this in a new relationship, but I’m also queer. I’m gay, demisexual, and pre-T transmasculine. At the intersection of so many marginalized identities, where does one’s self begin? How can I find companionship in a world codified to my exclusion?

I didn’t have all the answers. To be honest, I was missing most of the questions. But I’d gotten to the point in my life where I could finally move forward, and slowly begin the process of mending my life. Or so I thought.

I recently discovered that my insurance won’t cover fertility preservation procedures, so I can’t progress in my transition with my mind at ease. I’m beginning to question whether I’ll be able to harness a human right as basic as reproduction. Even so, I’m often told I should adopt. I can’t help but wonder if ableism isn’t at the core of that insistence.

There are many reasons I personally don’t want to adopt, not the least of which being that since I was young, I’ve dreamt of having a child of my own genetic makeup. I briefly digressed from this desire because I, too, feared that I’d pass on the less advantageous of my qualities. But, I must admit, I love life — even my life — and it’s not something I’d ever want to be denied to me on the basis of chronic or mental illness. It’s not something I feel should ever decrease my value as a human being, nor prevent me from being treated equally in the sight of all. And now I heartily extend that sentiment to my unborn, hypothetical child. If I can only find a way to have them.

Sure, I don’t leave the house often — though who does, these days? True, I can’t live alone. My best friends are online, and my conversations take place via text or Messenger. I can’t contribute to my family’s well-being in a strictly monetary way, but I can help in others. On my better days, I like to think that my existence alone might be compensation enough. I like to believe that each person’s value will be judged, if it must be at all, on the merit of their hearts and minds and not their bodies.

I came to the knowledge of my queerness late, all things considered. It was after 11 toxic years with the same man, and several others spent single. I wish I could have known sooner. I wish I hadn’t let people’s assumptions and prejudices convince me that I was “normal.” Perfectly mundane; nothing to see here, move along. I can’t overemphasize the importance of inclusivity and representation; I didn’t come out as “not straight” until my first viewing of “Love, Simon.” Before that, I didn’t have the words, much less the courage. I didn’t think anything good would come of it.

I was, thankfully, wrong. I’ve come out to the same people as LGBTQIA+ three times in my life, and each time refined both the process and the result. I’d never felt more comfortable with myself, my friends or my family. Each time felt like I was hitting a little closer to truth, a little nearer to myself. I’m finally on the path to becoming my truest and most authentic self, with hormones or without. And for that, I’ve never been more proud.

Happy Pride!