How 'Diagnostic Overshadowing' Endangers People With Intellectual Disabilities

Editor's Note

If you want to have a conversation with people who “get it,” join The Mighty’s Chat Space group.

Imagine that you are a young adult with a developmental or intellectual disability. You are minimally verbal (but have been labeled nonverbal) yet you understand a lot more than people think you do. You have been given an antipsychotic medication for a few months and have just started getting an increased dosage — part of your “plan.” Nobody explains the medication to you nor do they explain what adverse effects you may experience, especially with the increased dose.

You quickly experience the most frightening experience of your life — your tongue gets stuck in your mouth, you have trouble breathing, and your neck feels like it’s stuck in one position. You grab at your caretaker to try and tell the caretaker that you’re scared and need help. Your caretaker luckily realizes that you need medical help, so you get rushed to the hospital.

At the hospital, you hear several nurses and doctors say “calm down” and talk about you in front of you, but nobody talks directly to you. You are scared and nobody is telling you what’s going on, so you move in various gestures trying to communicate. The healthcare workers keep saying “challenging behaviors” and “SIBs” while they give you some kind of medicine through a sharp object into your arm. Nobody tells you this is an antipsychotic — the same medication that was causing you trouble in the first place.

Several hours later, another doctor finally examines you again after talking to your caretaker and reading your medical chart. This doctor says “dystonia” and “oculogyric crisis” — something to do with the muscles of your mouth and throat. Now you’re getting a medicine called Benadryl. You finally start to feel better — you start to breathe better and you feel your muscles relaxing. But you’ll never forget how you almost died as a result of people assuming that when you grabbed for help, it meant you were showing symptoms of aggression and self-injury behaviors attributed to the core characteristics of your disabilities. You were lucky to get help when you did — but what if that second opinion did not come along?

In Australia, a 28-year old woman with an intellectual disability died from cardiac arrest after undiagnosed meningitis; her clinical presentation of crying, distress and seizures had been assumed to be a “temper tantrum” and she was forcefully discharged from the hospital without any neurological scans or tests for infection.

In the U.K., a 30-year old man with severe learning and speech disabilities died of sepsis-related organ failure from bronchopneumonia. His avoidable death started with surgery for a broken leg, which resulted in a huge loss of blood. The blood loss led to a cascade of events, including status epilepticus after the hospital failed to give the patient a replacement epilepsy medication during his stay. After the man’s prematurely early discharge from the hospital, he developed a high fever, anorexia, insomnia, and self-injurious behavior. His GP saw him during this period, without a referral for a hospital admission — only prescribing antibiotics. Within a short time after the man’s next hospitalization, he ended up in the ICU and died of cardiac failure from bronchopneumonia-related septicemia.

In the U.S., a 59-year old woman living at a developmental disability center died from untreated neuroleptic malignant syndrome. The woman was inappropriately administered an antipsychotic, apparently to suppress the side effects of a seizure medication. After a full day of progressively worse muscle stiffening, the woman only received intravenous fluids without a neurological workup. After 10 days during which the muscle rigidity moved down to the rest of the woman’s body, the woman died from “polymyositis, or inflammation of the muscles.”

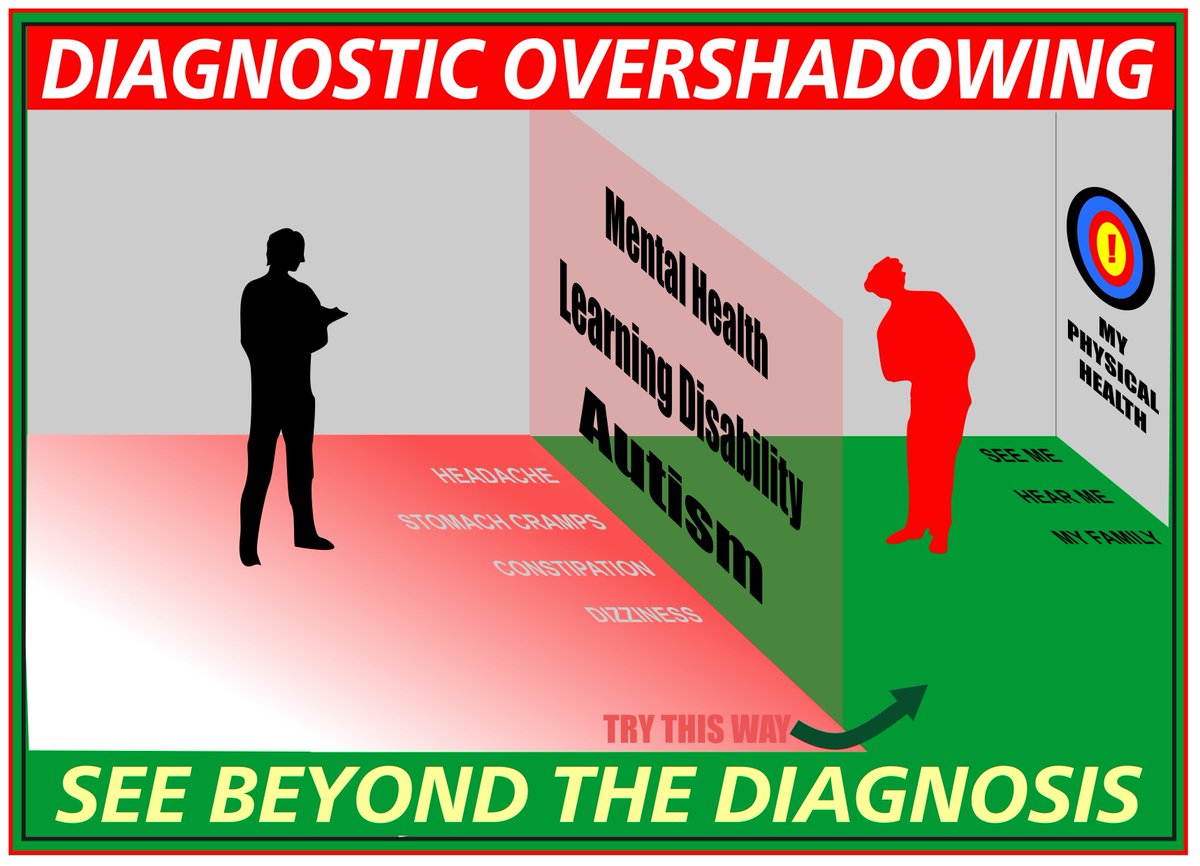

The above tragedies were the result of a dangerous and pervasive phenomenon called diagnostic overshadowing:

“When an emotional or behavioral problem is misattributed to the [disability] itself, rather than a comorbid condition.”

What We Do Know

A. Individuals with ASD/DD/ID are more likely to encounter barriers to receiving appropriate medical care compared to the general population.

B. Individuals with ASD/DD/ID have higher rates of comorbid and/or underlying medical conditions compared to the general population.

A. Barriers to Care

- Adults with autism spectrum disorder (“ASD”) face significant barriers to receiving appropriate and timely medical care, especially individuals with significant communication difficulties.

- Individuals with intellectual disabilities tend to be overlooked for movement disorders because physicians mistakenly attribute the patient’s abnormal movements to be a core symptom of the disability. “There is evidence that movement side effects of antipsychotic drugs are poorly assessed in people with ID who are under the care of secondary care services; this situation must change if medication is to be used in the safest and most effective way possible.”

- Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities are more likely to be inappropriately prescribed medications and experience increased incidence of adverse drug reactions. These adverse effects include:

o Dystonia: “sustained contraction of the muscles of the neck (torticollis), eyes (oculogyric crisis), tongue, jaw and other muscle groups”…can be “very painful and frightening to patients”

o Akathisia: “experienced as restlessness and unpleasant sensation of restlessness and the need to move, especially the legs,” “symptoms of anxiety, agitation or both” and “may be difficult to distinguish from anxiety related to [other primary psychiatric disorders].”

B. Medical Conditions in ASD/DD/ID

- In a study of “141 adult patients with mild, moderate, or severe/profound intellectual disabilities,” researchers found that the incidence of serious medical conditions was significantly higher in those with intellectual disability than the incidence noted in the population of those without intellectual disability.

- A U.K. population-based cohort study of 9,013 adults with intellectual disability (and a control group of 34,242 adults without ID) found that individuals with intellectual disabilities are more susceptible to neurological side effects of antipsychotic medications (tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome) than the general population.

- People with ID experience a higher rate of chronic health conditions, such as epilepsy and hypothyroidism.

So What Does This All Mean and What Can We Do to Help?

Medical care discrimination of patients with ASD/DD/ID is an unnecessary hazard to an already vulnerable population. Widespread diagnostic overshadowing in this population is harmful and even fatal. Individuals, their families and healthcare practitioners continue to voice their concerns about this issue, but their concerns have gone largely ignored. Public health and related government agencies must take an active role in creating and implementing policy change to prevent delayed diagnoses and missed diagnoses due to biases against individuals with ASD/DD/ID.

Everybody deserves appropriate medical care and to have signs and symptoms of illness taken seriously. Those with communication difficulties require higher attentiveness to medical needs.

On a positive note, diagnostic overshadowing is a habit that can be changed through education, outreach, and collaboration between individuals with disabilities, their families, healthcare practitioners, and others involved in the care of these individuals. This will require more than a piece of paper, more than a checklist, and more than a new bill. We need ongoing and intensive public attention to the issue to assure proper implementation.

The COVID-19 crisis has led to increased awareness of disability discrimination through rationing of life-saving treatment — let’s utilize this momentum to stop the pervasive and preventable disease progression and mortality of individuals who have been neglected for much too long in society. I hope this article serves as an invitation for ideas and collaboration to help address this silent and underlooked form of disability discrimination.

Getty image by WorSangJun.