Why Mitochondrial Disease Awareness Should Matter to All of Us

Mitochondrial Disease Awareness Week is celebrated globally during the third week of September to educate and increase awareness for those who are affected by this rare group of conditions.

The first mitochondrial genetic mutation causing human disease was identified 30 years ago by Douglas Wallace. Mitochondrial diseases are one of the most common inborn errors of metabolism – it is estimated that mitochondrial disease affects at least 1 in every 5,000 people globally.

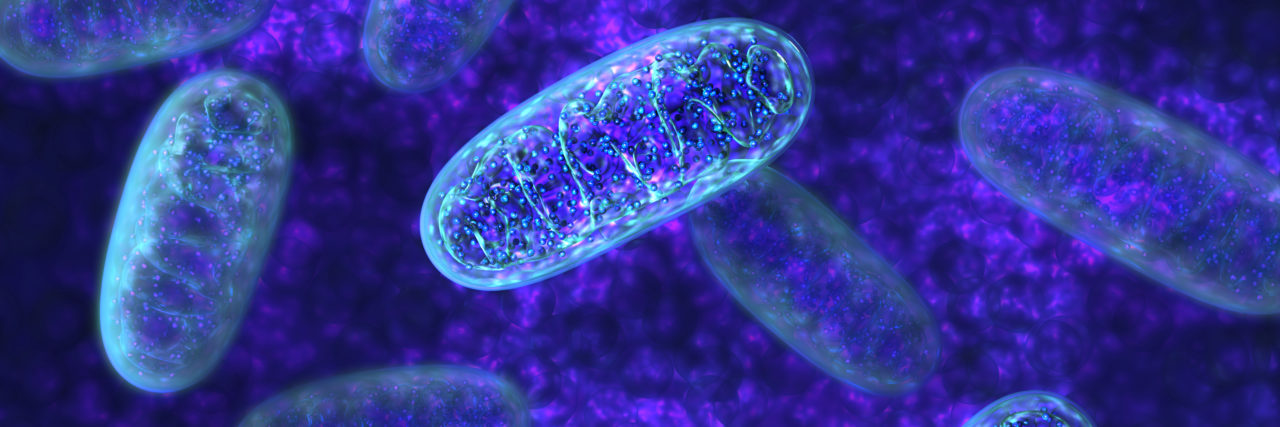

Mitochondria function as batteries that produce more than 90 percent of the energy in your body’s cells, and are really important in high-energy demanding organs such as your heart, liver, muscles and brain.

Did you know that mitochondrial dysfunction exists in all chronic diseases and cancers? It is a major factor in all of the problems with aging – loss of muscle, declining eyesight, lack of energy, wrinkling, inability to heal, mental decline, and organ failure. Someone in their 70s typically has only about 20 percent of the functioning mitochondria they had in their 20s. The more researchers learn about mitochondria, the more we learn about the link between mitochondrial dysfunction and common diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, MS, ALS, cancer, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogrens syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, irritable bowel syndrome, Burkitt lymphoma, and Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Most of us will have mitochondria-related problems at some point. If researchers learn to boost their function, to boost healthy mitochondria, or stave off the detriments, it could be a breakthrough for all of us.

Back in 2013, during my daughter’s two-year diagnostic odyssey to determine what was causing the atrophy of her cerebellum, was the very first time I heard about mitochondrial diseases. Like everyone else, I learned in high school that all of our cells, except red blood cells, contain mitochondria and that mitochondria produce the energy our cells need to function, to replicate, and to repair themselves. Essentially, they are the “powerhouses” of the cell. However, it wasn’t until 25 years later that I saw first-hand what happens when they do not function properly.

My daughter’s type of neurodegenerative mitochondrial disease, nucleotide binding protein-like (NUBPL), involves cerebellar dysfunction – progressive cerebellar and pons hypoplasia, hypotonia, ataxia, nystagmus, difficulty walking, intention tremor, speech articulation difficulty, and global developmental delay.

NUBPL is an iron sulfur (Fe/S) protein in humans that is encoded by the NUBPL gene, located on chromosome 14q12. It was discovered in 2010 — the year I was pregnant with my daughter –that NUBPL mutations in humans are a cause of mitochondrial complex 1 deficiency. Thanks to advances in genetic testing, in 2015 geneticists pinpointed the “cause” of her mitochondrial disease; however, we quickly learned that very little was known about the gene’s function or the long-term prognosis. At the time, she was only the fourth child diagnosed with this gene mutation in the United States.

I have spent the past six years advocating for mitochondrial disease on different levels, including legislative advocacy to mandate insurance companies cover supplements, writing awareness articles, and co-founding the 501c3 non-profit NUBPL Foundation to raise awareness, grow the NUBPL patient community, and fund research for the discovery of a treatment breakthrough. Together, our small but mighty community of NUBPL families are creating a legacy of hope and understanding for future generations diagnosed with this rare mitochondrial disease.

I am endlessly inspired by the strength and resilience of our community. For us, every single day is Mitochondrial Disease Awareness Day.

As the parents of children needing of a life-enhancing, life-saving treatment that does not exist or has yet to be discovered, we must fight each day to raise awareness and accelerate this research. Simultaneously, we face a life-altering, devastating diagnosis for our children, manage their day-to-day care and therapies, and paddle furiously to stay afloat and find a healthy balance in our daily lives.

I asked members of our community to share some personal insight about their own mitochondrial disease journey. Here’s what they said:

Courtney Jameson said, “When you’re told your child has a progressive neurodegenerative mitochondrial disorder, time stops for a moment. You can’t breathe. You lose a little piece of yourself and your heart shatters. And then, you pick yourself back up. You find hope, and you fight. You do whatever you possibly can to keep your baby healthy. You research, you raise money for the research, you meet with doctors, you share your story, your heart, your love and your hope. Because you’re your child’s rock. It’s up to you – and you will do whatever is humanly possible for them.”

“It’s difficult to articulate what happens to your world when your child is diagnosed with a neurodegenerative mitochondrial disease. In those first days, even weeks, confusion, fear, and despair consume you, leaving little room for optimism. Even in those moments though, as parents, you cling to the promise of hope. So, you resolve to fight. To become educated and to educate. To do anything within your control to ensure the greatest outcome for your child. Most moms and dads are advocates in one way or another. But when your child has a rare disease or a disability, advocate becomes your title — and you wear that badge with love and honor,” replied Jamie Blucher.

Alison Large responded, “The journey of having a child with a mitochondrial disorder is not an easy one. There are so many struggles. So much guilt, grief, fear and hurt. Grief that comes and goes like waves, and hits you hard as you realize yet another thing that your child can’t or won’t be able to experience because of their disorder. There are countless thoughts of guilt about whether you are making the right decisions or if your other family members are getting enough attention. There’s days of hurt for your child as they struggle to do the things that make them happy. And the fear, the debilitating fear of losing a part of your soul. Luckily there are a lot of wonderful things too, like joy, laughter, kindness, and the best…hope. The hope of new research, the hope of new skills learned, the hope of a future where other families don’t feel these feelings. There is so much love and community. All of these things give us the strength we need to power through this journey.”

David Faughn said, “When you get the diagnosis, in the space of a few words, what you imagine about the future changes. Things you never consciously thought about before are suddenly all you think about. You lose things you never realized you had. The little things, like teaching your daughter to drive and change a tire, pacing nervously on her first solo drive, and later as her curfew approaches, coaching her in soccer or softball, meeting her first love, dancing at her wedding… these everyday moments are gone. In their place is the knowledge that she may never play a sport, and never drive a car. In their place are fears that she will never have a first love, never be old enough to have a curfew, never get married. I still mourn these losses, while loving everything about my daughter. She is a perfect girl no matter how imperfect her circumstances.”

The truth is, no words can adequately describe the way you feel when you’re told your child has a progressive mitochondrial disease you’ve never heard of before. No words can describe what it’s like to hear from the doctor that you should just “take them home, love them, and spend as much time with them as you can.”

Naturally, many of us are doing all of those things — that’s parenting — but parenthood for me also means fighting like hell to raise awareness and fund the research to enhance and save my child’s life.

If someone told you your child was going to be hit by a train, you would do everything in your power to prevent it from happening.

This is why mitochondrial disease awareness matters.