Cheating at Eye Exams

I freely admit this since I’m sure the statute of limitations is up: I cheated at eye exams in elementary school. What would be the punishment anyway? Glasses? Contacts? Hybrid lenses? Painful cornea scratches? Eye surgeries? Been there, done that . Just let me clear my conscience since this is the only test I ever cheated on.

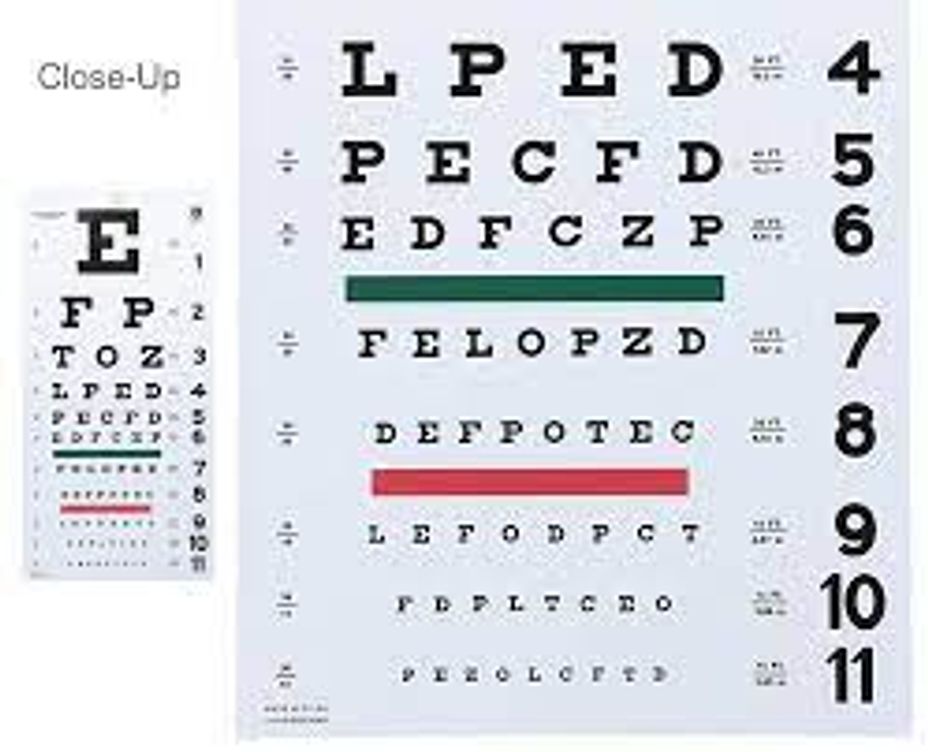

The annual eye exam was given in October and I was nervous. No one had told me to study. Mrs. Hottenstein put us into two lines–boys in one, girls in the other–and a fourth grader walked us down the hallway to the nurse’s office. The nurse, Mrs. Roberts, showed us the big black and white chart on the wall and the masking tape line on the floor. We would stand, she said, with our toes on the line and we would read the letters on the chart.

“And I am aware,” she said with emphasis, “you all KNOW your letters.”

Tommy Elliot shifted his feet a little. I’d come to school knowing my letters, but Tommy still struggled.

“Now,” Mrs Roberts instructed, “put yourselves in alphabetical order by your last name.” She shuffled a pack of white cards in her hands. We all assumed they were our permanent records, those bits of information that would follow us around the rest of our lives. “You’ll cover your right eye with one hand,” she demonstrated, “and read the chart, then do the same with your left eye. Everyone understand?”

We all nodded. She tapped the cards against the edge of her desk and waited.

We began to sort ourselves into order, helping Tommy find his place. My name started with a W, so –as always–I found myself near the end of the line that extended into the hallway. Through the open door, I heard the other children as they stood with their toes on the masking tape line and took the eye exam.

“E-D-P-T-O”

The letters, repeated again and again as students ahead of me read the chart, began a little sing-song in my head, almost like the alphabet song we’d sung in kindergarten.

“Z-L-P-E-D”

They fell into a rhyme, rhythmic and memorable. I started to hum to myself.

“P-C-E-F-P”

When a student finished, Mrs. Roberts made a note on their permanent record. Once in a while, she frowned and said, “I’ll need to call your parents.”

I cringed. I had no idea what the marks were, but I wanted to keep my permanent record spotless. No mark would ever besmirch it! No phone call to my parents would prevent me from my beloved school.

Because I DID love school, as much as I loved my well-worn teddy bear. I couldn’t imagine a fate worse than banishment from its green-tiled hallways, its chalk-scented classroom, its wooden shelves full of books with hard covers and full-color illustrations.

I continued listening to the litany of letters as I moved closer and closer to the masking tape line.

“E- D -F- C- Z -P”

They fairly danced in my head. Wasn’t that the same for everyone? How could Billy not know that it was “E -D” not “E -O”? And what was wrong with Hannah that she said “F” when it was a “P”?

Finally, it was my turn to put the toes of my black patent-leather shoes on the masking tape line. Only Seth Webley and Samantha Zebley were behind me. I gave my biggest smile to Mrs. Roberts, knowing it would make my dimples appear.

“Name,” she said without even looking up.

I took a deep breath. “Linda Karen Waltersdorf. I can spell it if you want.”

She tapped the white card, my permanent record. “I have it. Now, look at the eye chart.”

I turned to the wall chart that had been hidden by the heads of taller students, confidence radiating from my first-grade heart. This would be a piece of cake.

My heart sank. The black and white chart was a mass of blurred lines and squiggles, not letters at all. Where were the F’s and the H’s and the G’s the other students had seen? Where were the letters that had been my friends since I was four? If I couldn’t read the chart, my permanent record would be ruined. My parents would be called. I would fail a test I hadn’t even been told to study for.

The letters I heard the other students repeat continued to dance in my head.

“ E -F -P, T- O- Z”

Mrs. Roberts said, “Can you tell me the letters on the chart?”

I wasn’t sure I’d heard her correctly. “Tell you the letters?”

“Yes. If you can.”

Of course I could! I’d heard 23 other students say them! I couldn’t READ the blurry mess she claimed was the eye chart, but I knew what the letters were supposed to be!

I told her. From the E all the way down to the last letter I’d heard from Michael Schmidt: C. I sang those letters in the same little rhyme that had formed in my brain.

I looked at Mrs. Roberts.

“Excellent,” she said. “Just excellent.”

“I passed?” I gasped.

“Of course,” she said. “You can go back to your classroom.”

I skipped in my black patent-leather shoes back down the green-tiled hallways, inhaling the scent of chalk, knowing the wooden shelves with their hard-cover books were still mine.

It was with similar subterfuge and a good memory that I made it through to the 3rd grade before my parents discovered the ugly truth:

I couldn’t see worth a damn.