I’m new here!

Hi, my name is ESnider45243.

#MightyTogether …I’d like to know more about melanoma on my skin, I will soon have a 2nd lesion removed.

Hi, my name is ESnider45243.

#MightyTogether …I’d like to know more about melanoma on my skin, I will soon have a 2nd lesion removed.

In September of 2023, my brother died of complications from melanoma. The cancer had advanced to stage four by the time he was diagnosed, including three lesions in his brain and intrusions into his spine that fractured two of his vertebrae. At that point, he couldn’t lift more than twenty pounds without risking paralysis. The insurance he had through his employer was terminated three months after his diagnosis. It was contingent on his being able to work and he could not. He then obtained insurance through the state at fifteen hundred a month. He would have received sixteen hundred a month in SSDI if he had lived long enough to start receiving benefits.

My brother didn’t fear dying. He feared surviving if he would be bankrupt from medical debt. Our mother worked with a woman who died of cancer and her family was saddled with nineteen thousand dollars in bills that the insurance company would not cover. If my brother had lived, he would have had to spend ninety percent of his disability compensation on insurance; his fear of massive medical debt seemed to be well founded, given our mother’s co-worker’s example and the fact that the one hundred dollars left over after paying his insurance premium wouldn’t have gone as far as it used to regarding his other bills.

Actress and neuroscientist Mayim Bialik returned to acting when she became pregnant, because the Screen Actors Guild insurance was excellent, in her opinion. It was better than the coverage available to her when she worked in academia at any rate. On the other hand, when actress and writer Jennifer Sky developed tumors in her liver, she was dropped from that same insurance because she was too sick to work the requisite number of hours. All of this goes back to one of the reasons Barack Obama wanted to reform health care. He said that our system worked well when a person was healthy, such as Mayim Bialik through her pregnancy. The system fails when the person is seriously ill. Jennifer Sky with her failing liver, or my brother, with three brain lesions and counting, two fractured vertebrae and so many other tumors his PET scan was lit up like a Christmas tree.

A job doesn’t provide the best healthcare when your coverage evaporates when you need it the most. And please spare me any discussion about early detection and “responsibility” and the rest of that drivel. My mother’s insurance didn’t cover yearly physicals because the insurance company calculated that it was cheaper to cover the treatment for the relative few who would develop cancer then pay for everyone to get screened. My brother, despite Obama's best efforts, couldn’t afford coverage under the ACA during periods when he worked for employers that didn’t offer insurance benefits. I remember being greatly amused when officials and politicians would talk about coverage people can afford, as if anybody in government has any clue about that at all. My brother’s commuting costs were substantially greater than average for this state, because his job required him to travel to distant job sites. Those costs were not reimbursed by his employer, and he had the additional burden of funding a more robust and expensive maintenance schedule for his vehicle. Those expenses were also not reimbursed. He couldn’t have managed that and his other expenses if insurance premiums had consumed half of his salary.

You can also spare me any bullshit about how kicking undocumented immigrants off of Medicaid would have helped my brother. My state offers no services to undocumented people; you can’t cut a service that doesn’t exist. The states that do offer services to undocumented immigrants pay for those services out of state funds, as federal law prohibits the use of federal funds to pay Medicaid costs for undocumented people. Furthermore, most of the states that offer such services pay more in federal taxes than they receive in federal aid. (Mostly blue states.) If the cuts to Medicaid are uniform, people in red states will have services cut to greater extremes, because federal money makes up a larger share of the money available for Medicaid payments. Your cuts would have hurt him.

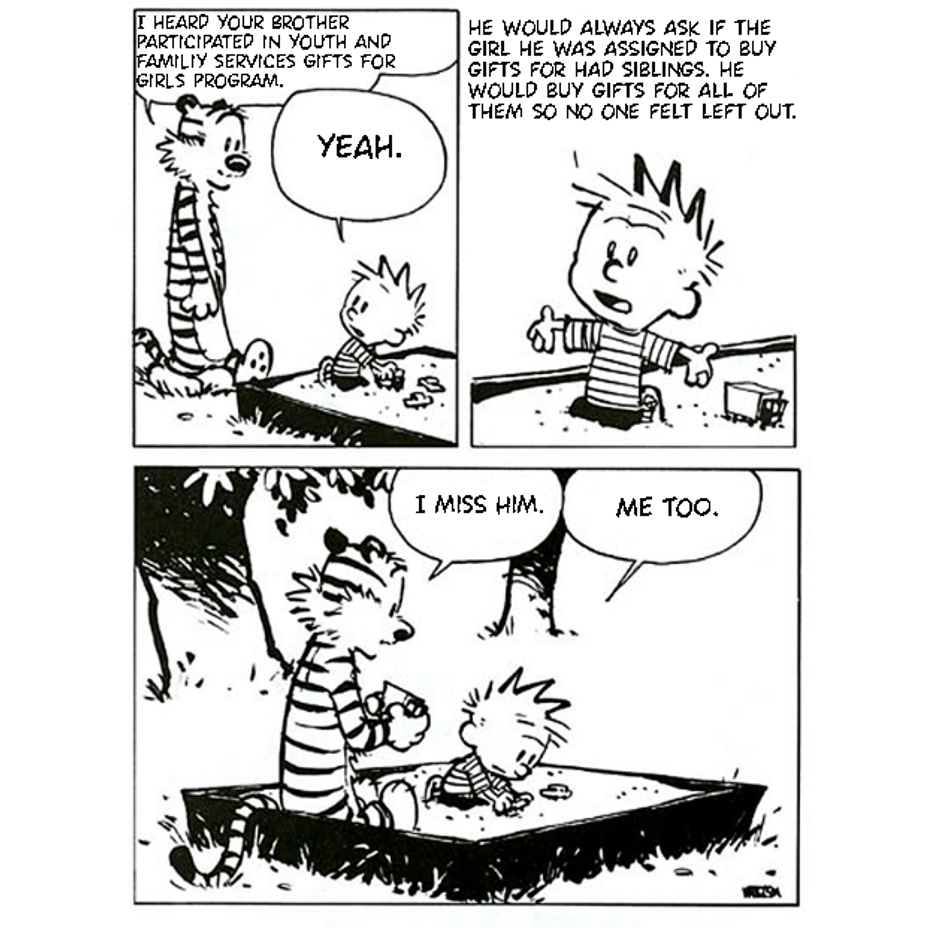

Every Christmas, my brother participated in a program that bought gifts for underprivileged children. He always asked that if his assigned child had siblings, that he be assigned the siblings as well. He would buy gifts for all of them so no one felt left out. This is the character of a man whose life you value so little, while aiding and abetting a man who spent sixty million dollars on a birthday parade for himself. In light of the cuts you say are necessary, I do not know how your government summons the strength to go on, making do with so little. #Depression #Suicide #MentalHealth #Trauma #PTSD #Disability #Cancer #Melanoma

I would like to connect with others that have been through Melanoma Cancer.

I recently was diagnosed, biopsied Jan. Met with Skin Cancer Dr and Facial reconstruction Dr yesterday. Surgeries are not scheduled yet, looking apprx 1 mth out for treatment.

Feeling a little lost, trying to see/find what I can know if surgery is the right direction. My husband doesn't think so. But says he will support my decision.

All my emotions are soooo jumbled at this time.

Hi, my name is bak70melan.

New here. I have recently been diagnosed with melanoma. It's located on my left cheek. Having a hard time with this.

#MightyTogether #Melanoma

Hi, my name is Rachels1981. I'm here because

For The past 5 days my life has been a whirlwind, one day I find out I have a form of melanoma, the next day I’m at the dermatologist who is telling me I’m having surgery on Monday. This was all from Thursday to Monday. I done good the day I found out, I even done great at the dermatologist, all the while knowing in the back of my mind it was lurking, waiting for the perfect opportunity to explode anxiety and depression. It all came out in a very ugly way toward my husband, all he sees is that I yelled at him, he doesn’t see the reason behind that yelling and can’t fathom how I changed so quickly. I try to explain to him, I only end up in agonizing pain and tears, trying to climb back to the top of the pit to try again but then I stop trying to explain, I withdraw, I have too much going on in my head, he is making it worse, I make him leave so my mind can take a break, it needs time, quiet from the voice of my of him being cold, snarky and not understanding. I have surgery today and I he will be taking me. I pray that my mind can handle this, that I will be strong enough to get through this day with someone that says they understand but in reality he does not. To deal with the person you love not really being there for you, but says he is and then facing a surgery knowing that person is my support really makes me feel helpless and afraid. I am a religious person and I know God has me, God is my only real solid support. What my husband lacks in understanding, God does, it will be God and I through this process. I am asking all the Mighty Community for your support also through this journey and if you read this all the way through, thank you that is all I need. Everyone here is in my thoughts and prayers.

Every day is a battle & every day I try but it is becoming very overwhelming & frustrating. Being in constant pain is something that is very challenging......

#ChronicIllness #ChronicPain #ChronicFatigue #MentalHealth #Selfcare #CheckInWithMe #Fibromyalgia #Anxiety #Depression #Endometriosis #Catheter #longcovid #COVID19 #BladderPain #SkinCancer #Melanoma

#Depression #Anxiety

To make this post more fully understood, I feel I need to go back several years. In 2015 my best friend was diagnosed with a rare but treatable skin cancer. She was diagnosed in October and told me not to worry because it was very treatable. Long story short, she went through he'll. My mom & I visited her in the hospital. After her family left us alone, she told us that her family didn't know yet but they had found a spot on her lung. This was right before Christmas and by the last week in January, she was gone. Her birthday was a few weeks later so I went up to spend some time with her mom and take her a gift. My mom wasn't feeling well so I made the visit alone. Four days later, I took my mom to the hospital. Three days after that she passed away. I had a mental and physical breakdown after that. The Drs found conditions that I must have had for years. I was so busy taking care of other people in my life that I ignored my own health. Fast forward 5 years. I'm no longer able to work but was coming to grips with my new normal. Then my brother passed away 5 years and 10 days after my mother's death. So, also in Feb. Aside from my husband and my stepdaughter and her family, my family had all but abandoned me.

This year in October, I had a pap come back with ASCUS and positive for HPV 33/58. Those are high risk for causing cervical cancer. Not the highest but high. I went through colposcopy and then a few weeks ago a cold knife conization. My anxiety was through the roof constantly waiting. Meanwhile my cousin was going through treatment for the second time with cervical cancer. Here it is the holidays and I was trying to stay positive. I wanted Christmas to be special in case it was my last one or in case I would be going through treatment. My stepdaughter had my granddaughter text me to invite us up Christmas morning to "hang out". No food. No celebrating. Just sit there. Keep in mind, she is fully aware of my diagnoses and the procedures I had gone through and the upcoming biopsy for me. I figured they needed a day to just chill. I didn't care what day we celebrated Christmas so I offered to do it at our house. I was sent a text dripping with attitude letting me know that they would have to decline. No explanation. No offer to do it at a different time.

So, praise God, my biopsy came back negative. I don't know whether my stepdaughter knows or not. She hasn't asked so, I haven't told her. I am not healing well from the procedure itself yet. So, I am supposed to take it easy. I purchased some things to make everyday life easier in case I had to go through any treatments. They've been sitting in the boxes since the beginning of December. All they required was installing pull out drawers for our cabinets. So, measure and drive 12 screws. Keep in mind I am disabled and he does maintenance for a living. I've been having extra trouble with my feet lately. He let me know that it would be nice to have instructions. They came with instructions and a template. Now for some unknown reason he is giving me the cold shoulder and barely speaking. He's treating me as though there is no reason that I shouldn't be taking better care of the house.

I need to go to a clinic about 2 hours away for a procedure for some of my GI issues. For this one, I could drive but I get extremely anxious driving in that city. I know it's going to be a fight because he keeps asking if I "need" a driver. He reluctantly drives when I am put out for procedures locally. Now, I went to the Dr this week and there is a spot on my foot that may be melanoma.

I don't feel like I have anybody to count on anymore. I've always been there for everybody else. Why do people peel away when you need them most?

I'm sorry for the long post but as I said, I have nobody to lean on. I needed to get this out. Just needed to vent.

BTW...I installed the pull out drawers.

Thanks for reading.

Since August 3rd - I had COVID for 15 days, kidney stone, double kidney infections for 6 weeks. I then had a breast biopsy that indicated something was wrong. Lumpectomy 11/29 that was invasive carcinoma. Fell in the driveway. 12/19 two lymph nodes removed (negative for cancer). 12/28 my PCP referred me to a dermatologist, melanoma on bridge of my nose and 2 questionable moles on the back of my right should. 4 solid months of exhausting, painful issues on top of my chronic back pain, fibromyalgia and gastroparesis.

I did not decorate for any of the holidays. Haven’t worked in the yard ( which I enjoy) haven’t sewn or crafted. Basic meals for my husband. I’m not in a funk, I’m hurting, tired and now stressed.

Once the pathology they sent out today for more tests comes back from my cancer it’ll tell them if I need chemo on top of the radiation.

I want off this train of woes