#Vacterl Adult Introduction

I joined years ago and decided to make an intro post finally…

I was born with a rare birth defect and now I’m a #Vacterl adult, married to a Danish guy who happens to be a VACTERL adult as well (we met at a support group in 2005 and married in 2011 ). I’ve had over 200 surgeries. Every VACTERL person is different… for me I have: #scoliosis , #analmalformation , #malabsorption , #tef , #solidarykidney , and a #limbdeformity . I catheterize through my bellybutton.

I’m a journalist turned medical PTSD expert, MFA graduate, disability advocate and memoirist, with some hospice admin on the side. As for hobbies: I crochets as therapy, binge watch random shows (I watched ten seasons of Hoarders in a row), and I’m a bookworm. I talk on my IG/FB/threads about my health, what I am reading and my crochet projects. I love Mexican food, historical fiction and mystery novels and I love watching police procedurals.

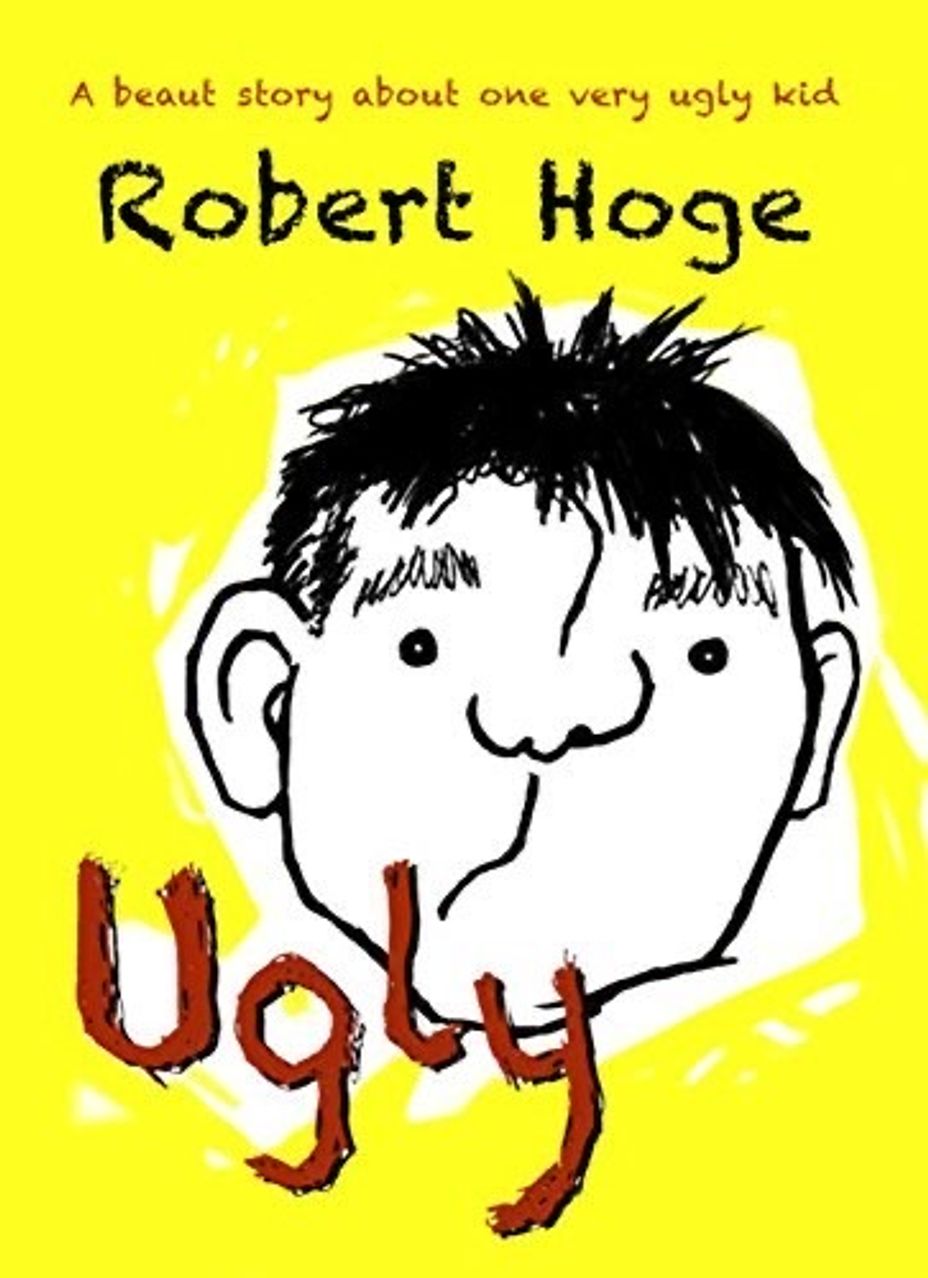

Photo is of me and my husband.