#MentalHealth #Selfcompassion

Transform your mindset.

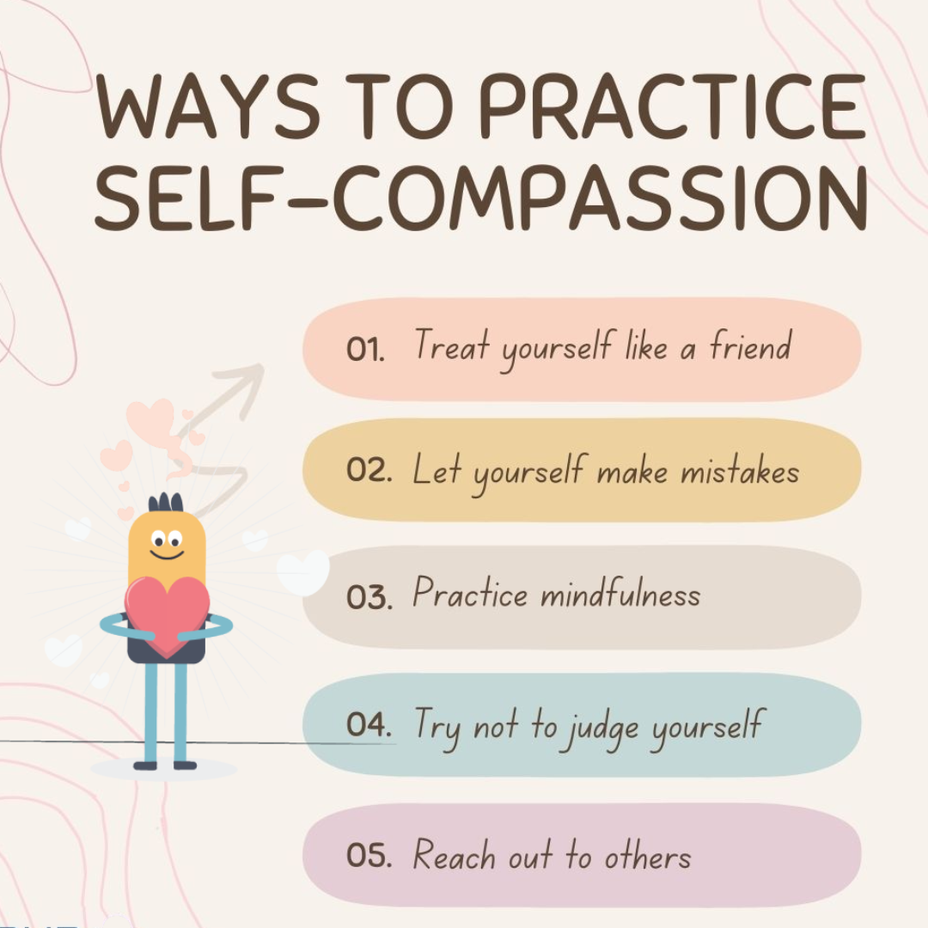

Sadly, it’s often challenging to lift yourself up (particularly if you’re feeling really low or ashamed), but if you want to create compassion for yourself, you have to change your mindset.

For me, self-compassion started with changing my thoughts. I started focusing on the fact that my behavior was bad, not me. Once I started labeling behavior (instead of myself as whole), I was able to be kinder to myself and open up my mind to the possibility that I could make changes.

Forgive yourself for your mistakes.

Forgiveness is vital for self-compassion. We all make mistakes, but not all of us forgive ourselves for them. Depending on the mistake, this can be a very daunting task, but keep in mind that you cannot go back (no matter how badly you might want to), so the best thing to do is to choose forgiveness and forward motion.

Whenever I did something inappropriate, instead of shrugging it off or excusing my behavior, I started apologizing for it, both to others and to myself. Again, I focused on the fact that I wasn’t bad; it was my behavior that was.

Strive to avoid judgments and assumptions.

Though assumptions and judgments are often based on experience or knowledge of some sort, it’s very hard to predict what will happen in life. When you judge yourself or make an assumption about what you will do in the future, you don’t give yourself an opportunity to choose a different path. Instead of limiting yourself, be open to all possibilities.

In my situation, I started assuming that I shouldn’t go to an event because I would inevitably cause a scene and have to leave. Little did I know that I’d eventually learn, with the help of therapy and self-compassion, to socialize sober. I had assumed that I would always be “wild,” but I’ve learned that you cannot know the future. Assumptions will only inhibit you.

Find common ground with others.

While self-compassion is about the way you care for yourself, one of the best ways to cultivate it is to create connections with others. When you open yourself up to sharing who you are with others, you’ll soon see that you’re not alone.

We all struggle to treat ourselves with kindness, and recognizing this can make the struggle more manageable.

At some point, I began admitting to friends and family that I had a problem. It was difficult to open up emotionally, but the more I did, the more I discovered that I wasn’t alone. Creating these stronger emotional ties made it so much easier to deal with my personal shame and to work toward more self-compassion.

You can refer to this:

resiliens.com/resilify/program/self-compassion